Sennet is an associate dean of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and associate professor of piano at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She is a voting member of the Recording Academy, a public voices fellow with The OpEd Project and has recorded all 19 Bach keyboard suites as part of her three-volume series “Bach to Black: Suites for Piano.”

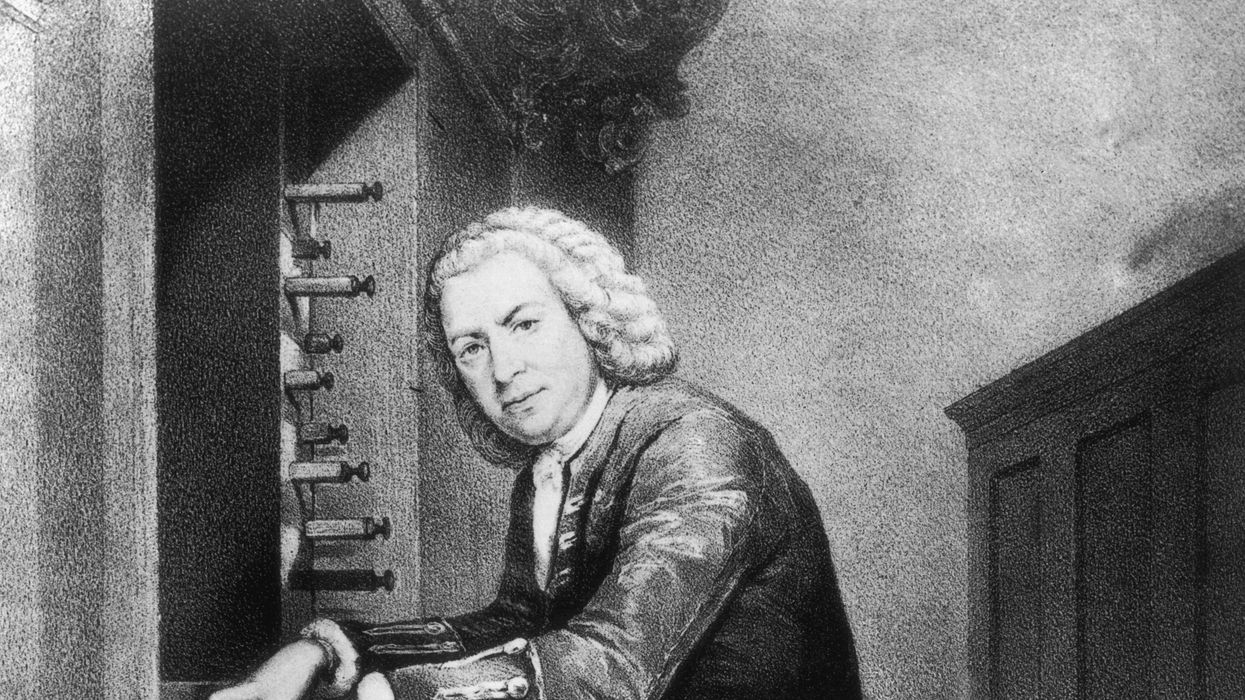

Johann Sebastian Bach continues to be a force of extraordinary influence across classical music, jazz and beyond.

Yet this consistency has often led to misconceptions about excellence as well as exclusion of many underrepresented musicians, scholars and concert patrons. It doesn’t have to be this way: Many communities are highlighting the work of Black artists such the Harlem Chamber Players.

Traditionally, throughout history, other composers are evaluated in comparison to Bach. As a Black woman, academic and classical recording artist, I have often heard the question: “Can she play Bach?” As a long-time performer, a recording artist for more than a decade and an educator for more than 15 years, yes, I regularly play Bach’s music.

In a 2022 study, researchers at the University of York found there is an “overall consensus” that Bach’s music “constitutes a transition point between intermediate and advanced musicianship.”

In the recent book, “ Expanding the Canon: Black Composers in the Music Theory Classroom,” editor Melissa Hoag writes that “taking the first step of addressing music by non-White composers might demonstrate an acknowledgment of Black culture and history, a recognition that Black composers exist and have existed for a long time, and a belief that music by Black composers is worthy of our time and attention.”

Both works show how strong emotions and opinions emerge across the classical music spectrum, including who is considered to meet the so-called gold standard of music performance.

While there have been recent efforts to be more inclusive in music performance and education, a separation remains in what many consider “high art” and who gets to be a part of it.

Conversations on race and diverse programming in classical music have increased in recent years and led to awareness in many spaces. For example, the Grammy Awards expanded the voting membership to ensure wider representation across all music genres.

But bias continues to be a concern.

When I was a teenager, a once-trusted mentor referred to me using a dated and racially offensive term in a reference letter to a summer piano program.

As a professor, it is upsetting to be excluded from faculty meetings where decisions are made regarding courses and teaching, having my academic and musical credentials unfairly questioned, and being labeled “angry” or “reserved.”

Like many other Black artists, I strive to counteract such biases by bringing awareness by highlighting diverse musicians and composers in the classroom and beyond. Classical music must not be just for the “elite.”

Growing up, I was aware that there were not many Black classical pianists. The late Natalie Hinderas, famed concert pianist and teacher at Temple University in Philadelphia, was one of the first Black female pianists whose performances I came across during my college years. As I began research on Black composers, I listened to her electrifying recording of the “Piano Concerto” composed by George Walker.

Other Black composers include Florence Price, whose music has recently gained renewed interest, and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a British composer. James Lee III, composer and professor at Morgan State University, was featured on the recent Grammy-nominated recording, “ American Stories.”

Though there is some representation, there are still fewer Black classical musicians overall.

I love performing Bach’s music, and musicians can continue broadening the scope of what constitutes excellence. As with Bach, we can foster more avenues for further introspection and study behind great works by composers of color, such as The Center for Black Music Research in Chicago or “ The Timeline of African American Music.”

It is essential to create opportunities to make music by composers of color more available through workshops, schools and concerts. Nonprofits such as St. Louis-based Pianos for People help make piano lessons more accessible for musicians of all ages and backgrounds.

For organizations focused on classical music, it is necessary to offer innovative ways of programming, as seen with Four Seasons Arts — which has sought to diversify audiences and their artist rosters alike in the San Francisco Bay area for more than 40 years — and consider values of conduct and inclusion for patrons. One doesn’t always have to default to Bach.

The courage to speak up about inclusion and accessibility in classical music is a powerful tool to connect individuals and communities. There must be more.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room