Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair of Political Science at Skidmore College and author of “A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law.”

This is the latest in a series to assist American citizens on the bumpy road ahead this election year. By highlighting components, principles and stories of the Constitution, Breslin hopes to remind us that the American political experiment remains, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, the “most interesting in the world.”

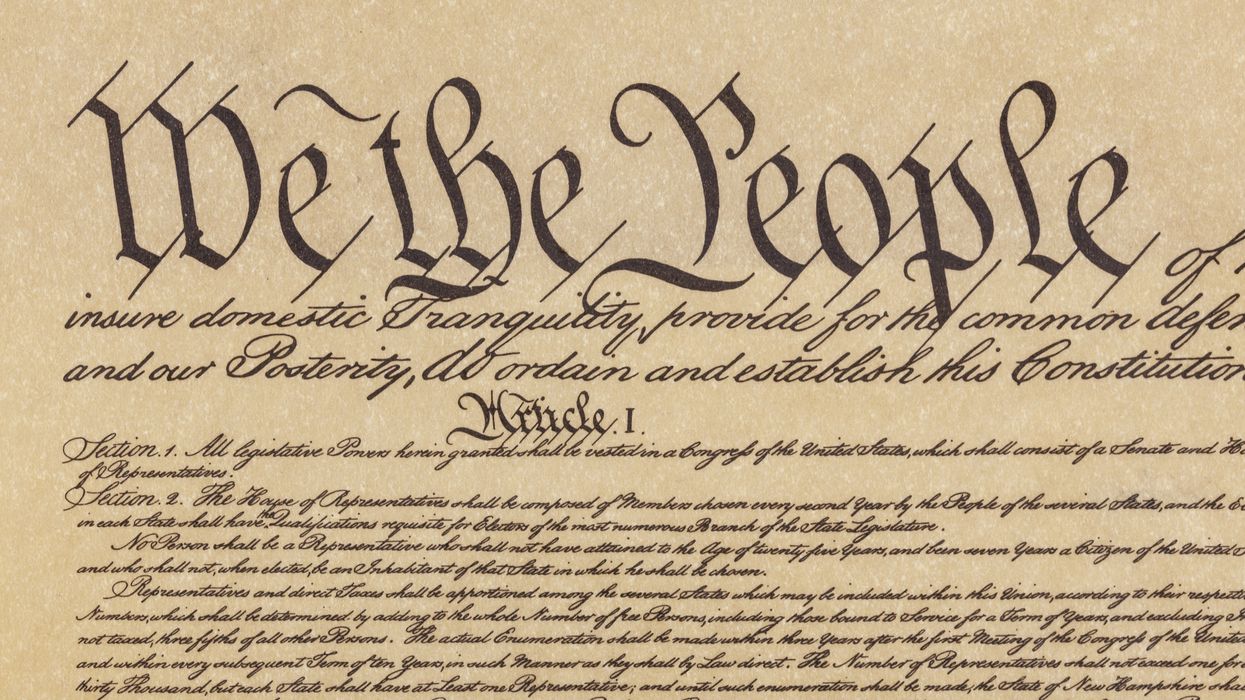

In these challenging political times, I find it helps if we look for inspiration to the sacred texts of our secular civic religion. Look no further than the Constitution’s Preamble — 52 words that have stirred generations past and present. Those famous aspirations — promises, really — are the country’s calling. To “form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty” are America’s objectives, its aims, its ambitions. In short, they are the nation’s collective mission.

They didn’t start off that way.

If James Madison was the brains behind the U.S. Constitution, Gouverneur Morris was the conclave’s poet. Dubbed the “penman of the Constitution,” Morris’s style and prose proved invaluable in a nascent country trying to find its footing. Fresh off a bloody revolution and the failure of the Articles of Confederation, the stakes for delegates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention were high. Word choice for the unratified constitutional text would matter. Nobody understood that better than the delegate from Pennsylvania with the wooden leg and the acerbic wit.

Nowhere is Morris’ eloquence more powerfully displayed than in the soaring verses of the Constitution’s famous Preamble. Things didn’t start off that movingly, however. The first draft of the Preamble was disappointingly mundane. In many respects an afterthought, it was seen by some in Philadelphia as irrelevant and unnecessary. There was no discussion of any prefatory statement at all during the convention’s deliberations.

It was the Committee of Detail, the group responsible for taking the resolutions agreed upon and producing an initial draft of the Constitution, that first added a preamble. The words were uninspiring. It read, “We the People of the States of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia, do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.”

Gifted with the quill, Morris was not going to endorse such a dull passage. A preamble, he knew, had to sing; it had to stir the souls of a skeptical populace. Morris understood that preambles serve multiple purposes: 1) They announce the very purpose of a constitution; 2) they articulate a nation’s top priorities; 3) they use exalted language intended to inspire; and, 4) they clearly, and unequivocally, identify the sovereign. (More recent constitutional preambles also invariably tell the story of a nation’s shameful or troubled past — South Africa’s is probably the best example — but that was not the common practice in the 18th century.)

Morris relished the task of crafting an introduction to the Constitution that would endure through time. His first order of business was to shift the locus of power from the individual states to the whole, undifferentiated “People.” It was a mighty lift. Most in the early Republic identified themselves as citizens of the states in which they resided. Thomas Jefferson famously pronounced, “Virginia, Sir, is my country.” So did John Adams, though his country was Massachusetts.

The importance of Morris’ revision cannot be overstated. The revolutionary transfer of political power from the states under the Articles of Confederation to the national government under the Constitution was denoted by his pen. Turning “We the People of the States” into “We, the People of the United States” marked a complete philosophical transformation. Federal political power would forever derive from the enthusiastic consent of the universal governed and not from the reluctant generosity of the discrete states. Sovereignty shifted right then and there. The notion of a collective national people was born with that critical modification. We became true U.S. citizens in that moment.

Morris’ next order of business was to announce the very purpose of the Constitution itself. The Pennsylvanian knew that it could be a powerful instrument to achieve the highest order ambitions: justice, freedom, security, prosperity and so on. In sum, the ingredients of a “more perfect Union.” But these ambitions had to be conveyed, they had to be revealed. Don’t leave the people guessing as to what the Constitution endeavored to achieve, Morris thought.

Morris’ final maneuver was to double down on the importance of the Preamble to the flow of the entire Constitution. The Committee of Detail version implied that the Preamble was considered different, apart, distinct from the seven articles that made up the body of the charter. We know that because the draft used the word “following,” as in “We [the people of the separate states] do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.” Morris thought the Preamble was an essential element of the constitutional text, equal to, or even greater than, the clauses that trailed. He replaced “the following” with the word “this.” The new language read, “We, the People of the United States of America ... do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” It was a small, but powerfully significant revision.

And just to bring it all home, Morris concluded the Preamble by repeating the phrase, “United States of America.” A “Constitution for the Government” simply would not do, Morris asserted. It wasn’t any old “Government” we were constituting. This Constitution and these United States were special.

Now, to our collective challenge. We stand today polarized. Do “We, the People” now take it mostly for granted that the country’s mission, both at its Founding and presently, is to “form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty?” I hope not.

Let’s assume we don’t take our collective mission for granted. We are still obligated — compelled even — to ask a few fundamental questions: How well are we doing in achieving these highest order principles? How successfully have we established Justice? Are we enjoying a period of domestic Tranquility? Do we honestly secure the Blessings of Liberty for all? Do we even know how to promote the general Welfare anymore? Gouverneur Morris would expect that asking these questions — and then honestly answering them — is the least we can do.