Exultant crusaders against partisan gerrymandering are vowing to hold North Carolina politicians' feet to the fire until the state's legislative maps are drawn more fairly — while also looking beyond the borders. They are hailing a state court's redistricting decision as a landmark ruling with the potential to benefit their cause across the country.

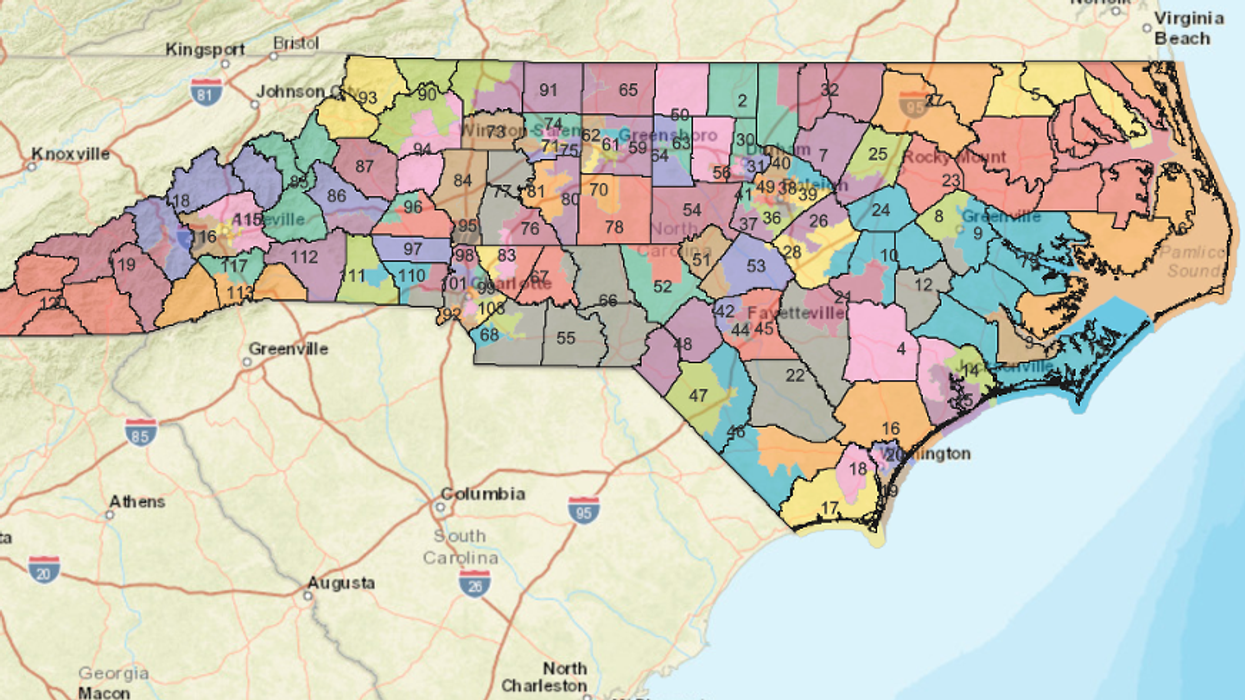

Just 10 weeks ago, the Supreme Court held that the Constitution provides no opening for challenges in the federal courts to even the most brazenly partisan mapmaking. But in a dramatic reversal of fortune for political cartographers — and not just in North Carolina — a bipartisan panel of three judges in Raleigh ruled unanimously Tuesday that the state House and state Senate lines are so contorted to favor Republicans that they violate a broad array of Democratic voters' rights under the state's constitution.

The GOP leaders in the state capital, who have been contesting almost a dozen different anti- gerrymanderinglawsuits (some successfully alleging racial motivation) while hoping to keep their district lines intact, announced they were at last conceding defeat. Rather than appeal to the state's top court — a long-shot prospect given its lopsided Democratic majority — they said they would get to work on new maps right away.

"Nearly a decade of relentless litigation has strained the legitimacy of this state's institutions, and the relationship between its leaders, to the breaking point," said Phil Berger, the Republican majority leader of the state Senate. "It's time to move on."

The judges gave the legislators two weeks to come up with new maps to be used in 2020 and said they could not take into account any data about election results. They also ordered that the maps be drawn entirely in public, with the computer displays visible to all.

"What's crucial now is ensuring that the legislature fully complies with the court's order and draws new legislative districts in a timely fashion, with full transparency and robust public input, absolutely free from gerrymandering," said Bob Phillips, executive director of North Carolina's chapter of Common Cause, a lead plaintiff in the case.

Beyond that, democracy reform advocates said they would begin strategizing on when and where to replicate their newfound path to victory in the courts — and where to pursue other options. "The fight will go on in state courts, in legislatures, and through ballot initiatives to ensure every voter across this country has a voice at the polls," said Common Cause's national president, Karen Hobert Flynn.

The North Carolina ruling said the maps violated the state Constitution's clauses guaranteeing equal protection under the law, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. The heart of the 357-page decision, though, was a broad interpretation of the five words comprising Section 10 of the document: "All elections shall be free."

That language "guarantees that all elections must be conducted freely and honestly to ascertain, fairly and truthfully, the will of the people," the judges wrote. "It is not the free will of the people that is fairly ascertained through extreme partisan gerrymandering. Rather, it is the carefully crafted will of the map drawer that predominates."

While the federal courts have no role in refereeing such disputes, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the 5-4 majority in June, state constitutions could "provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply."

Roughly half of state constitutions have free election clauses, meaning their state would theoretically be open to an argument similar to what worked in North Carolina. In addition, almost all the state constitutions have a right-to-vote guarantee that could be the provision on which partisan gerrymandering opponents hang their cases.

And, even if there's no rush to the courthouses with such arguments, the prospect that state courts might step in to stop the most egregiously partisan maps could prompt future political line drawers to take a somewhat less aggressive approach.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court cited provisions of its Constitution in striking down a partisan gerrymander in 2018. The court threw out the state's GOP-dominated congressional map, enabling Democrats to gain a handful of seats.

The North Carolina judges set a tight Sept. 18 deadline because legislative candidates have already declared and the first round of primaries is scheduled for February. The maps will then need to be drawn once again — this time, along with every other electoral map in the country — when the 2020 census provides the population details to shape the contours for the coming decade.

While both parties gerrymander to benefit their continuation in power whenever they can, Republicans have had more opportunity to do so in recent years because they control more statehouses than the Democrats.

Tuesday's ruling did not cover the congressional boundaries, which are also drawn to favor the GOP, and so next week's special election to fill one of the House seats will not be disrupted. But attorneys for the winning side said the decision's reasoning would also apply to the map of the state's 13 U.S. House seats and that a lawsuit to strike down that map was being contemplated.

The House map has routinely produced 10 Republican winners. And all decade, Republicans were consistently able to win at least three-fifths of the seats in both of the state's legislative chambers despite only winning about half of the total statewide vote. The GOP majorities were veto-proof until after last year's election, when they dipped to 54 percent of state House seats and 58 percent of state Senate seats — even though Democratic candidates won a majority of votes statewide.