Richie is senior advisor and co-founder of FairVote, a nonpartisan electoral reform organization.

Imagine it’s election night 2024. A few close swing states will decide the presidency – and test the health of our democracy. In that scenario, we can be certain of two facts: Neither Joe Biden nor Donald Trump will win a majority of the vote, and votes for independent and third-party candidates will dwarf the final margin.

Dissatisfied voters regularly peel off to insurgents like John Anderson in 1980, Ross Perot in 1992, Ralph Nader in 2000, and Jill Stein and Gary Johnson in 2016. With Robert Kennedy polling in double-digits, and Libertarians, Greens and Cornel West to appear on many state ballots, there’s a whole shadow campaign emerging. Democrats are spending millions against these candidates, while Republicans are eying whether they can repeat the 2016 playbook — in which Trump flipped the decisive states of Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin with an average vote share of less than 48 percent.

There’s a proven solution to the “spoiler” problem ready-made for American politics: ranked-choice voting. Australia has an average of more than five candidates in its RCV elections without any “spoiler” talk. Maine and Alaska already will use RCV for president this year. If all states had RCV, there would be no worries that a third-party candidate could tip a state — and thus the White House — against popular will.

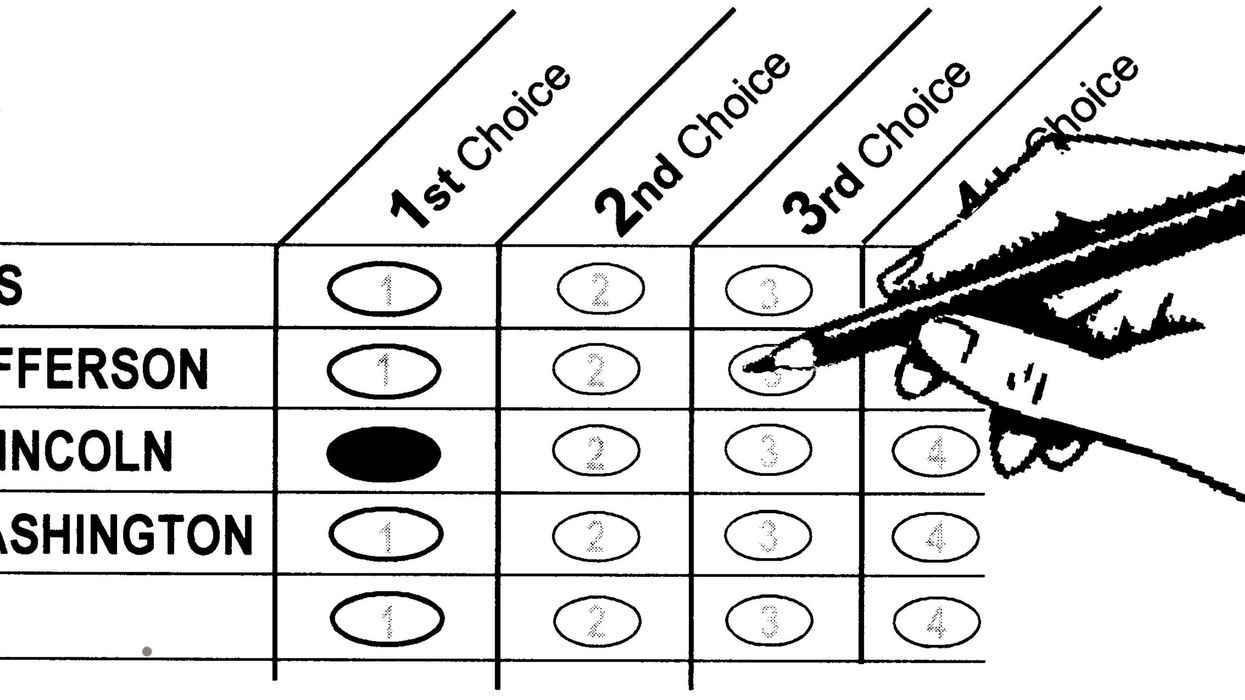

Instead of indicating a single choice, RCV voters get to rank the candidates first, second and so on. If no one wins by securing more than half of first choices, the trailing finishers are eliminated and ballots for those candidates count for their next choice. The final “instant runoff” between the top two candidates ensures a representative outcome without the costs and burdens of a December runoff election.

Alaska adopted RCV for presidential elections in 2020 and Maine after legislative action in 2019. But why have 48 states not passed RCV — particularly the seven swing states that will decide this November’s election? Why are the collective decisions of voters unwilling to settle on the “lesser of two evils” a bigger wildcard than Trump’s criminal trials and Biden’s age?

To be sure, change is happening, 50 American cities and hundreds of NGOs use RCV, with generally strong support for it in exit polls. RCV has won 27 consecutive city ballot measures, and four states and D.C. may vote on adopting RCV statewide this November. It’s been a clue on Jeopardy and in national crossword puzzles.

A few proven approaches will help scale RCV faster. Perfection is illusory, but we should never settle for less. Voters of all backgrounds easily rank things every day, and all jurisdictions should use well-designed ballots and tested voter education models to allow them to do that in RCV elections. RCV results should be as fast, transparent and auditable as non-RCV ones. States should buy voting equipment that makes RCV as easy to use as flipping a switch.

These changes are coming. Many cities release preliminary RCV tallies on election night and embrace best practices on transparency, audits and timely data releases. Now that all modern voting equipment can run RCV elections (a real concern for cities looking to adopt RCV in the 1990s and 2000s), policymakers are aligning on standards to enable vendors to offer RCV as a default option. More jurisdictions are investing in good ballot design, intuitive results displays and voter education.

Effectively ending the presidential spoiler problem by 2028 is within reach by focusing on the swing states that decide the White House. RCV is already on the ballot this November in Nevada, and active movements in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin are pushing for change.

With Americans fundamentally restless with their ballot choices, the spoiler problem can’t be wished away. It’s time to take RCV national to accommodate voter choices and reward our leaders for seeking to represent a majority of Americans.