Shepherd represented Utah in the House of Representatives from 1993 to 1995 as a Democrat.

First a personal story. Shortly after President Trump was elected, I attended a town hall meeting called by my congressman. It was held in the large auditorium of a Salt Lake City high school, and about 2,000 people attended. As a former member of Congress who had held many of my own town hall meetings before anxious and upset people, I was interested in watching how this meeting would be managed. I knew the audience was mostly made up of Democrats and the representative was a Republican. Most of his constituents did not live in the city and neither did he.

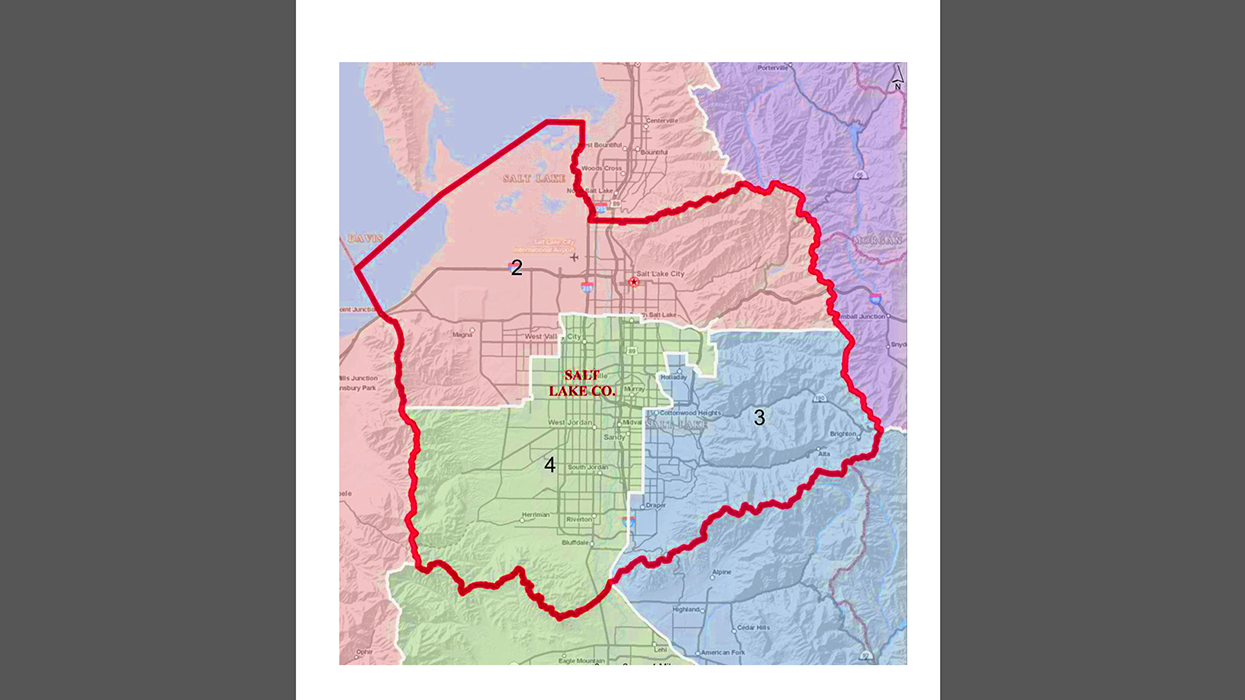

After an introduction by the district director, the congressman came forward to speak. His first words, after welcoming us and noting the huge size of the crowd, were to say he assumed people were there because they didn't agree with his stands on many issues. Then he pointed to a pie chart showing where in Utah he had won votes in the last election. "As you can see here," he said smiling, "it doesn't really matter what you think about me or these issues." He then pointedly noted his votes had come from elsewhere in the state – the mostly rural, much more conservative part of Utah.

A solidly Democratic region in the middle of a mostly Republican state, the Salt Lake City metro area has been split like a pizza between our four congressional districts so that the community's voting power is diluted. As a result, unrepresented voters alternate between desperate attempts to overcome the system and total indifference to the political process. Meanwhile, voters in Republican areas, always sure their candidates will win all but the rare competitive races, often stay home. As gerrymandering has increased, Utah's voting record has declined. Democrats don't vote because they know their vote doesn't count and Republicans don't vote because they know their vote isn't needed.

Neither Democrats nor Republicans like what gerrymandering was doing to democracy in Utah, so we came together to form a bipartisan coalition, Better Boundaries, that successfully passed a redistricting reform ballot initiative last fall. Fortunately, the Utah Constitution enshrines the right of citizens to make laws directly without the approval of those who most benefit from gerrymandering.

It's important to be clear about the psychology of gerrymandering. It's not a partisan issue. Democrats are as fierce as Republicans about holding onto power when they have it. No one, absolutely no one, gives up power easily. That is why it took a whole initiative, two years and hundreds of thousands of people in Utah to insist that it be done.

People want their voices to count and to be heard. In gerrymandered districts neither can happen. People want their elected officials to listen and to be accountable. In gerrymandered districts, that does not happen. Good government relies on giving people pathways to their government so that they don't feel helpless, or indifferent, or angry. Gerrymandering seals off all those pathways.

Finding a fair and balanced way to draw district lines so elections are competitive and all are represented is critical to the health of our democracy. The Utah lesson, perhaps, is that if a fair and balanced solution to redistricting can win voters' approval here, it can be done anywhere.