For those who rank political muscle-flexing in electoral mapmaking among the most menacing threats to democracy, the Supreme Court has provided an array of suggestions:

Convince your self-aggrandizing state legislators to cool it. Look for protection in the courts of your own state. Persuade Congress to set a national rule that politicians cannot draw election boundaries, or else come up with a national standard for partisan excesses in setting the lines. Or orchestrate statewide ballot initiatives turning the congressional and state legislative cartographic powers over to independent experts.

In short, the justices said Thursday, do anything you like except look for us to referee the limits of partisan gerrymandering; the Constitution does not contain an explanation for how to do it, and so we are not going to.

"No one can accuse this court of having a crabbed view of the reach of its competence," Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority. "But we have no commission to allocate political power and influence in the absence of a constitutional directive or legal standards to guide us in the exercise of such authority."

The 5-4 decision, with the five conservatives prevailing over the four liberals, means much of the nation's political balance of power will continue to be shaped by Republicans and Democrats motivated by nothing more than perpetuating their own influence.

That is, unless voters in states from Florida to Oregon, and from Maine to New Mexico, decide to confront their own lawmakers in coming years and use other means to scrub partisanship out of redistricting. Which is why democracy reform activists, while lambasting the ruling, hailed it as an opportunity to harness the power of grassroots activism.

The court "chose to keep intact a corrupt system that lets politicians choose their voters, instead of the other way around," said Scott Greytak of RepresentUs, one of the most ambitious and well-financed groups advocating for a broad spectrum of political process changes. "Fortunately, we have a plan for unrigging American elections that doesn't rely on the Supreme Court: passing powerful anti-gerrymandering laws state by state."

To that end, his group is arranging for a flood of phone calls on Monday urging New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu, a Republican, to sign legislation adding his purple state to the roster of places where electoral mapmaking has been taken away from the legislature and turned over to an independent commission.

Ballot measures to similarly depoliticize mapmaking were approved by the voters last fall in Michigan, Colorado, Missouri, Ohio and Utah – bringing to 14 the number of states (with 173 House seats, or a two-fifth of the national total) where the next decade's congressional boundaries will not be drawn exclusively by legislators.

A somewhat overlapping roster of 20 states, with an estimated 105 million voters, have taken state House members and state senators out of the process of setting the contours for their own seats.

It is too early to assess which states, if any, will have redistricting reform referenda on the ballot in November 2020.

But the advocacy group Stand Up Republic announced it would seek to get initiatives on the ballot in every state without an independent districting panel.

"The majority of Americans support gerrymandering reform, they just need an outlet to work for change," the group said. "Americans of all persuasions want to have a competitive electoral process. Now, even more than before, we need citizen-led reform."

The long backstory

Four years ago the Supreme Court voted 5-4 to uphold the constitutionality of such independent commissions. One of the dissenters was Roberts, who described the panel created in Arizona as a "deliberate constitutional evasion" in which the legislature subcontracted out its mapmaking obligations under Article I in a way that "has no basis in the text, structure or history of the Constitution."

The chief justice appears to have had a change of heart, however, because on Thursday he wrote approvingly of the state commissions being created on the order of voters in 2018. He also pointed out the merits of state Supreme Court rulings against overly partisan gerrymanders in Florida and Pennsylvania.

He also mentioned several bills in Congress and paid particular attention to HR 1, the comprehensive political process overhaul that has been shelved by the Republican since the newly Democratic House passed it along party lines this spring. The bill would require all states to establish 15-member panels of political independents to draw House boundaries under certain ground rules, including protecting "communities of interest" and avoiding partisan imbalances

The cases decided were challenges to the Republican-drawn congressional map of North Carolina, a closely divided purple state where the delegation has remained reliably 10-3 for the GOP, and the districts successfully drawn by the Democrats to assure they would win seven of eight House seats in Maryland, where the party usually wins no more than three-fifths of the vote.

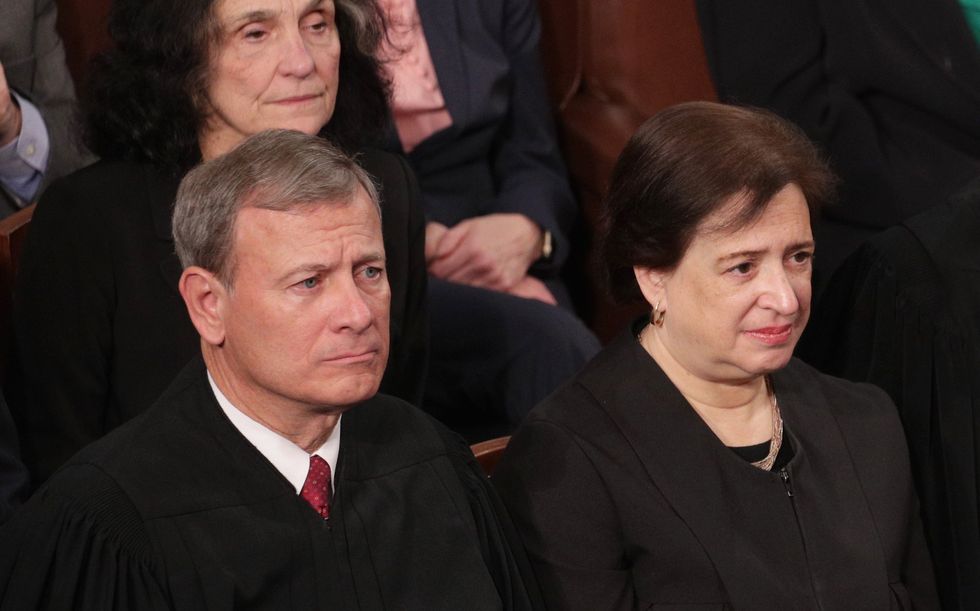

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion; Elena Kagan wrote for the minority.Alex Wong/Getty Images

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion; Elena Kagan wrote for the minority.Alex Wong/Getty Images

"These gerrymanders enabled politicians to entrench themselves in office as against voters' preferences," Justice Elena Kagan wrote for the four liberals in her dissent. "They promoted partisanship above respect for the popular will. They encouraged a politics of polarization and disfunction. If left unchecked, gerrymanders like the ones here may irreparably damage our system of government."

Earlier court rulings against both the Maryland and North Carolina maps have since been echoed by federal judicial panels in three other states that had declared the boundaries of Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin were all unconstitutionally drawn by Republicans to favor their own. Those rulings were all effectively nullified by the high court.

To be sure, in the short term, the ruling will embolden those who control state governments after the next election to be as aggressively partisan as they want in the national redistricting that begins in 2021, once results of the next census are final.

The census citizenship factor

If advocates for a less polarized democracy saw a silver lining Thursday, the Supreme Court's final day of decisions for this term, it came when the justices at least temporarily blocked the Trump administration from including a citizenship question in the census.

It's unclear whether the administration has time to address the court's concerns before the practical deadline for starting to print census forms. And after the ruling, President Trump tweeted that he wants to delay the census if necessary.

The court said the Commerce Department's rationale for adding the question was inadequate. Opponents say the real motives are clear.

One is to assure that millions of mostly Latino immigrants ignore the census, fearing it would lead to deportation, and so in the next decade Democratic-leaning areas where they're concentrated lose legislative seats that instead go to more Republican areas. The even more nefarious motive, they say, is to abandon two centuries of precedent and draw boundaries using only the populations of citizens instead or residents.

If either of those things happens, democracy reform advocates say, the result would be a dangerous accelerant for the partisan gerrymandering the federal courts will now stand clear of.

The Supreme Court has said repeatedly that drawing the lines to deny racial minorities a fair shot at electoral representation is unconstitutional. An open question now is whether mapmakers whose true aim is to disenfranchise African-Americans or Latinos will be able to defend themselves from racial gerrymandering allegations by saying their motives are purely partisan.

Protecting political power has been part of the redistricting process as long as there is been Congress, although the technological advances of recent decades have permitted politicians to custom design their own own territory with incredible precision and virtually guaranteed electoral safety.

None of the current court has any experience with that. That may be one reason why Roberts referred repeatedly in the rationale for his opinion to past writings by Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, who was a state senator in Arizona before joining the court. O'Connor, who was the last person on the court to have run in an election, left 14 years ago.