Tobias is a reporter for Signal Ohio.

Early voting starts Oct. 8 for the Nov. 5 election, which includes a ballot measure known as Issue 1. In short, it’s an amendment to the Ohio Constitution that would change the state’s system for drawing political district maps for Congress members and state lawmakers.

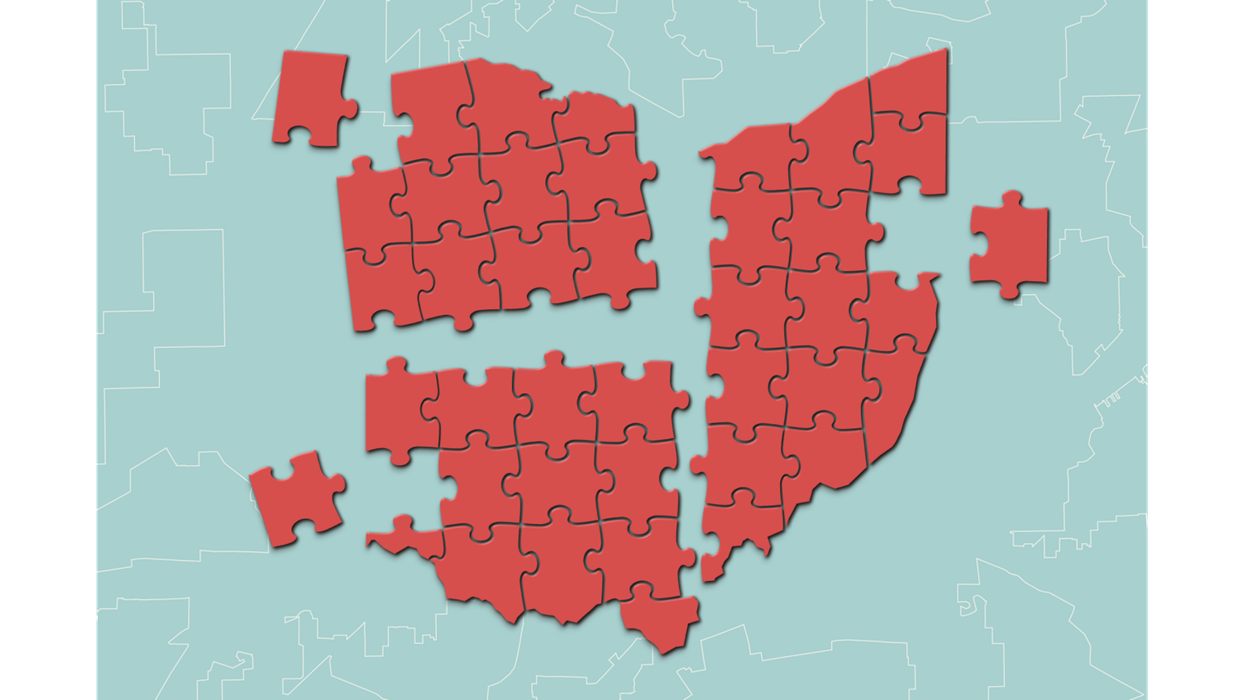

But Issue 1 has sparked a lot of questions and confusion about what exactly it will do – and if it will end gerrymandering. That’s a word that references how the process of map making can be manipulated to the benefit of one party. In short, the parties’ experts know how to study past elections to predict who voters may support in the future, among other tricks of the trade, to try to maximize their chances of winning.

Both the campaigns for and against Issue 1 are claiming their side is against gerrymandering. This could leave voters to wonder: Who’s telling the truth?

To help voters navigate the campaign and make an informed decision, Signal Ohio is offering this nonpartisan guide about Issue 1.

This includes a comparison of the official ballot language, which summarizes the measure’s effects for voters, with the amendment’s official text. We also offer an explanation of key points of the text to help translate its technical and legal jargon.

First, it’s important to provide a bit more information about Issue 1 and the backstory of the ballot language summary.

What does Issue 1 do?

The proposed amendment describes a multi-step process to change redistricting, the drawing of boundaries that define the political districts for state lawmakers and members of Congress. If approved by voters, the amendment would require redistricting to happen in 2026 and then every 10 years starting in 2031. It would start with replacing the Ohio Redistricting Commission, a panel of elected officials that’s currently controlled by Republicans, with a citizen’s commission that couldn’t include elected officials, lobbyists, party officials, candidates or their immediate family members. It also would set rules supporters say are meant to limit gerrymandering by requiring the maps to favor each party to win a share of districts similar to the parties’ share of the statewide vote.

Who wrote the ballot language?

State Republicans who oppose Issue 1 wrote the language that Ohioans will see on their ballots when they make their vote. The ballot language has no legal effect – it only summarizes what Issue 1 would do. Allowing ballot summaries was a reform passed in the 1970s to avoid having to publish lengthy and technical amendments directly on the ballot that might confuse voters. But research has shown that ballot language also can influence a measure’s chances of passing depending on what it says, especially in close elections.

What voters should know about the Issue 1 ballot summary

The pro-Issue 1 campaign filed a lawsuit in August calling the summary biased. But the Ohio Supreme Court’s four Republican justices largely upheld the summary as fair and accurate, although the court’s three Democrats disagreed.

The main “yes” campaign group, Citizens Not Politicians, wrote the amendment and is funded by a collection of organized labor and other left-leaning groups, although its chief spokesperson is Maureen O’Connor, a retired Republican chief justice of the Ohio Supreme Court. Like the state ballot board that wrote the amendment summary, the anti-Issue 1 campaign has close ties to the Ohio Republican Party.