Katz is the community engagement manager for Made By Us.

This year, Made By Us is hosting the second annual Civic Season, a time to connect with the past, take action in the present and shape the future by participating in activities contributed by over 300 history and cultural organizations nationwide. And what better way for young Americans to celebrate what they stand for than with a bright and inspiring poster?

The Civic Season official poster asks participants to share what they stand for and how they do it, but there’s a story behind this moving poster – it was printed by Globe Press, history’s go-to printer for everything from culture to politics to music.

Made By Us' community engagement manager, Cameron Katz, sat down with Allison Fisher, manager of the Globe Collection and Press at MICA to learn about the history of the press and how art is impacting our democracy today.

Cameron Katz: On your website, it says that Globe was founded over a card game. Can you tell us that story?

Allison Fisher: Lore has it that a printer and businessman were playing cards and decided to go into business together. They folded a map of the U.S. in half and the crease landed on Baltimore. We can’t confirm that is how Globe Baltimore came to be; however, descendants of Norman Shapiro, the original owner of Globe have been researching their family history and found that the Shapiros were a family of printers who founded more than a dozen print shops across the U.S. in places like Baltimore, Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis and Atlanta. Some used the name Globe, others operated under different names.

Samples of historic posters from the printers at Globe Samples of historic posters from the printers at Globe Samples of historic posters from the printers at Globe Samples of historic posters from the printers at Globe.Globe Collection at MICA

Samples of historic posters from the printers at Globe.Globe Collection at MICA

What a fascinating history. So, can you walk us through what the printing process is like?

Globe is a working collection, which means that we use beautiful wood types and printing blocks from the collection to make new work. Globe is known for its use of Day-Glo colors, bold bursts of colors, and gothic wood type. When we are designing something like a concert poster, we start with the black text layer first and set the type. We pull a single proof of the type on a letterpress and scan the print to lay in colored backgrounds digitally. True to Globe’s history, we screen print the background one color at a time. Screen printing is a process where you have a mesh screen with a stencil that allows ink to pass through for the image to be printed. We then put the type back on press and the final letterpress layer is printed.

Back in their heyday, Globe also built the text layer first, but then instead of using digital tools, they would use wax paper and an X-Acto knife to cut a stencil for screen printing. Historically, Globe did not get client approval before printing a job. You called in your order and told them the who, when and where. Clients put a lot of trust in Globe to deliver eye-catching posters. Today, most of our clients want to see a proof of the design before we print.

Globe’s process is unique because we are mixing screen printing and letterpress rather than doing one or the other. Globe started using this combination in the 1950s so we are carrying that tradition forward.

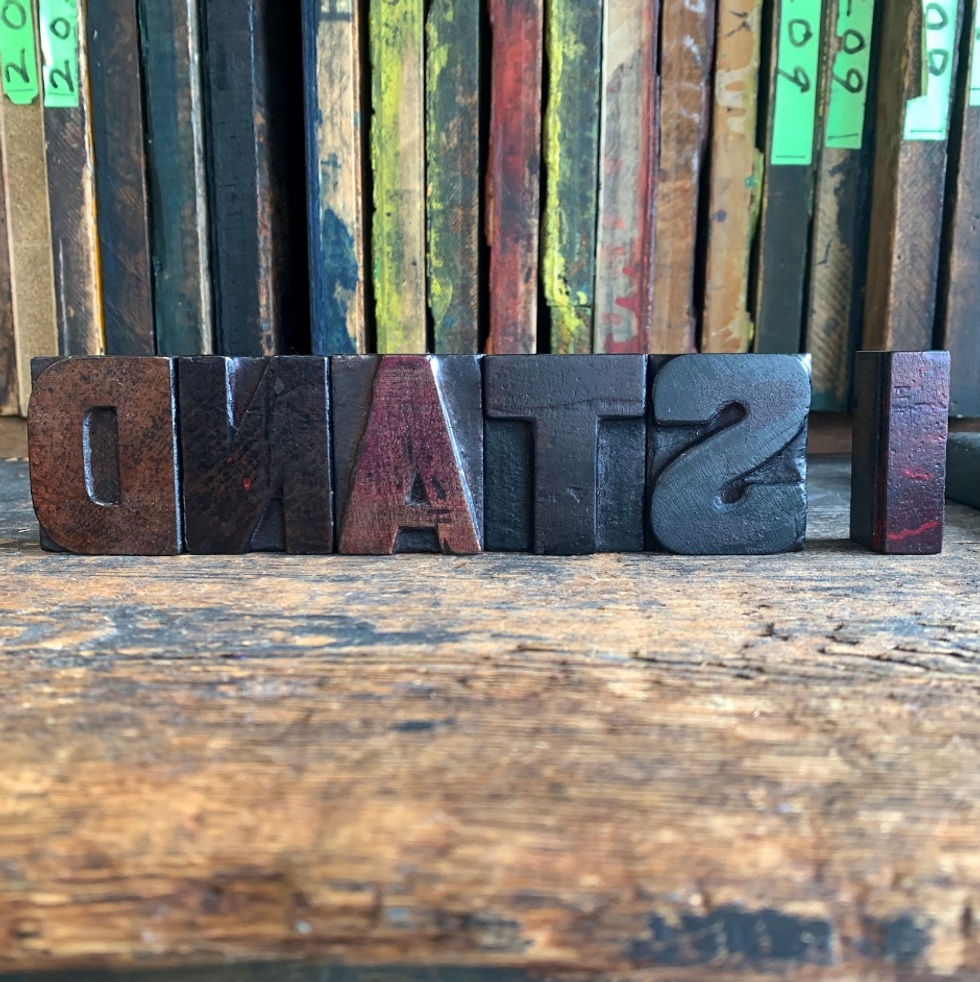

Letterpress type created this year’s iconic Civic Season posters that read: I stand for __ when I ___. Globe Collection at MICA

Letterpress type created this year’s iconic Civic Season posters that read: I stand for __ when I ___. Globe Collection at MICA

It’s really interesting to see how Globe has been able to maintain many of its historic practices while still bringing in today’s technology. On that note, how do you think that the importance of posters in American culture has changed over time?

My favorite definition of “poster” comes from Poster House in New York City, who is actually in the Made By Us partner network. They define a poster as “a public-facing, printed notice meant to persuade, entertain, or influence.” Posters used to be a primary means of communication. It was an inexpensive way to communicate to everyday people, but as technology evolved, we started getting our public-facing information from new, faster and cheaper sources. Posters were a struggling industry in the '70s and '80s when many cities passed "post no bills" laws that could leave you with hefty fines for hanging them. For many poster shops, that was the final straw and they were forced to close.

For many people posters have taken on a commemorative role, we don’t see a poster and go to a concert because it persuaded us, we buy the poster at the concert to remember the experience. I think in the last few years posters have begun to have a resurgence, both as a means of advertising and civically. We work for a lot of clients in Baltimore and D.C. who love the Globe style. They know that a Globe poster brings a sense of nostalgia to their audience because generations of people grew up seeing them on every corner. We see posters at protests – they express the sentiment of the crowd. Posters are ephemeral and accessible. You do not need to have access to technology to make one of your own. It can be done at home with what you have on hand.

And that’s one reason why so many artists came to Globe over the years. What else brought so many iconic voices, like Marvin Gaye and the Beach Boys, to Globe?

Globe printed inexpensive posters for everyday people, but there are a few things about Globe Baltimore that I think really made them a go-to printer for so many artists. Globe posters were cool. They used fluorescent colors with black, so against the backdrop of bricks, trees and roads, they stood out. Fluorescent colors reflect light if they were illuminated by a street light or headlights, so you could read them at night. Plus, Globe had a staff artist named Harry Knorr, who was likely a sign painter by trade. Harry’s lettering complemented the gothic type and gave the poster rhythm and bounce.

Another reason many artists used Globe was because they did not turn away business based on the color of your skin. Globe printed for thousands of Black artists during segregation. Artists knew they could rely on Globe at a time when getting on the radio had a lot of barriers and newspaper ads did not reach a lot of people. Posters were inexpensive but effective – you could hang a poster that thousands of cars a day would see on their way to work. If you hang another one across the street they see it again on their way home.

It’s interesting to learn about Globe’s operations during the late 20th century when there was so much social change happening. In that vein, why do you think art is important to democracy?

For lack of better wording, democracy can feel very corporate – slick sans serifs, clean design and slogans developed by PR people can feel very run of the mill and exclusive. In a time where the future of democracy is incredibly fragile, art can be a way to engage people who feel excluded from the democratic process. Art should make you think and ask questions.

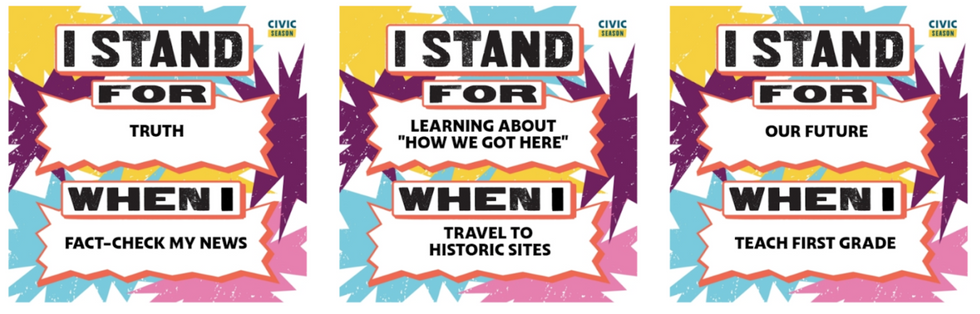

Create your own poster at TheCivicSeason.com/Share. Made By Use

Create your own poster at TheCivicSeason.com/Share. Made By Use

So how do these posters inspire civic participation today?

The posters Globe created for Civic Season asks participants to fill in the prompt “I stand for ____ when I ________.” The blanks are to be filled in by participants of all ages, backgrounds and orientations. Leaving space to be filled in means viewers become active participants. The posters are also framed out by a border of suggestions for how to become civically engaged in everything from voting to neighborhood clean-up efforts — a lot of people already participate in civic engagement even if they don’t call it that!

The design is inspired by materials from Globe’s archive, wood textures, bursts of color, and bold wood type. The design is meant to be loud and joyous.

This has been so great! Thank you so much, Allison!

Thank you!

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Trump needs to get ready for the blowback