Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair of Political Science at Skidmore College and author of “A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law.”

This is the latest in a series to assist American citizens on the bumpy road ahead this election year. By highlighting components, principles and stories of the Constitution, Breslin hopes to remind us that the American political experiment remains, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, the “most interesting in the world.”

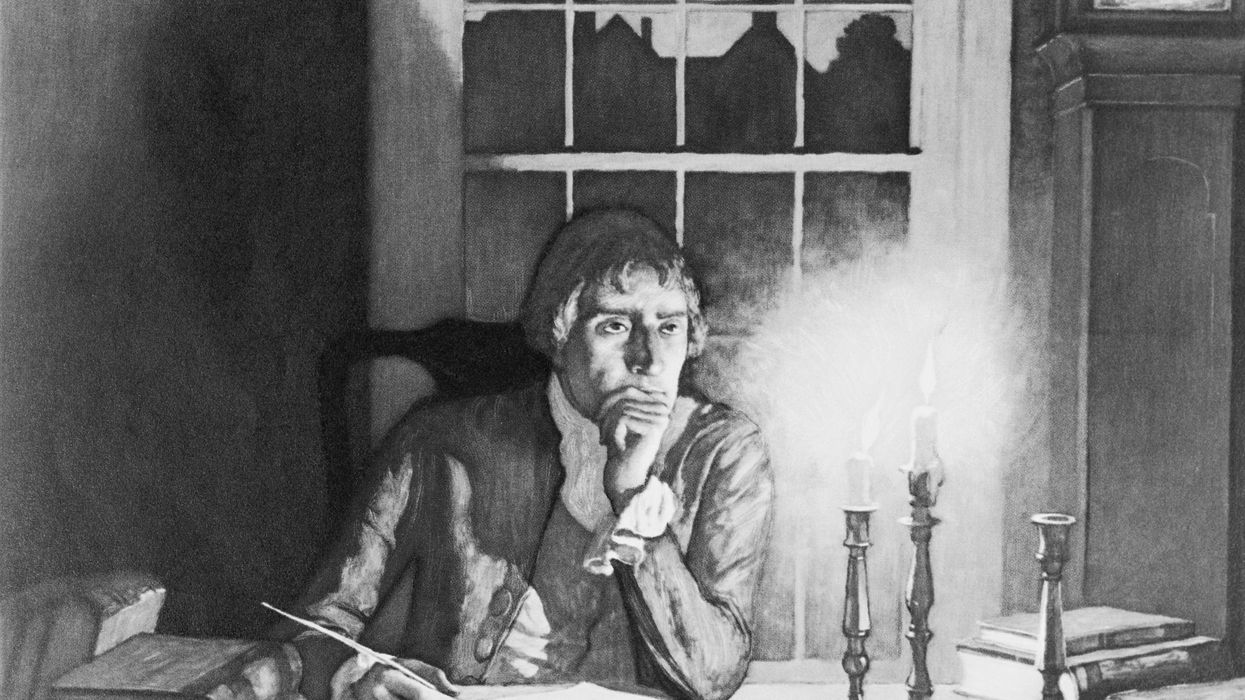

Thomas Jefferson dropped the mic. Few have done it better.

The most elegant prose stylist of the Founding generation, Jefferson put his greatest compositional artistry into the Declaration of Independence. The words still stir the soul. “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness…” Pure poetry.

He goes on: “But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security.” Inspirational. Brilliant.

The famous introductory paragraphs of America’s birth certificate practically soar off the parchment. The great historian Pauline Maier called Jefferson’s document “American Scripture” — divinely inspired and reverentially sanctified. She was right. The Declaration of Independence is the Old Testament of America’s civic religion. Its concluding sentence is the Book of Genesis.

And I would argue that Jefferson’s greatest prose, his true virtuoso performance, his most imperative message, comes in that concluding sentence. It is his “drop the mic” moment: “[F]or the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence,” Jefferson writes (assisted by the wordsmiths of the Second Continental Congress), “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

What does the Declaration’s powerful closing passage have to do with the state of contemporary U.S. politics? A lot actually. Much more than we suspect. Indeed, the message Jefferson sent — as well as his hope for a resolute American citizenry — has mostly vanished in history.

To be sure, men of the 18th century were deeply flawed. They tended to be patriarchal, paternalistic, chauvinistic, bigoted, egoistic, manipulative and vain. Many were racist. Most were intolerant. Some were shamefully abusive. We should never pardon such reprehensible behavior; different times will never justify morally abhorrent conduct. But the men of the early Republic embodied one personal characteristic that is sorely missing in today’s polarized political environment: altruism. The heart of an 18th century citizen was, politically at least, selfless and noble.

These figures understood that the principal aim of government was to benefit the common good, that the honorable citizen was motivated not by what might be favorable for himself but what was in the best interest of the entire community. Achieving “a more perfect union” was a shared enterprise that required self-sacrifice. Choices that might be personally hard to swallow would be defended, albeit reluctantly, because they were collectively necessary. There was a greater good out there, and that greater good frequently clashed with one’s private interests. Personal sacrifice for others — for that greater good — was honorable in the arena of politics. Even Madison, who feared the influence of private interests (factions) and doubted human character (men are not angels) trusted the strength of his contemporaries’ civic altruism.

The noble sentiment was movingly captured by the Declaration’s concluding sentence. Note the order of pledges: “our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.” Jefferson placed honor last because it was the most esteemed. Men preferred death to dishonor.

Note also that honor is “sacred.” It is touched by the divine. To willingly sacrifice one’s honor was sacrilegious, profane. To recognize what was in the best interest of the polity and still favor one’s private interests was ignominious.

Next, note that the pledge is a collective one. The Declaration of Independence was signed by individuals. Jefferson could have written, “the undersigned pledge their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor;” but, no, instead he uses terms like “we” and “our.” He is tapping the power of the collective.

And, finally, note the subtle shift in audience in that closing sentence. The Declaration is an announcement; it is an advocacy piece. Jefferson is trying to convince the colonists and the world of the unforgivable conduct of the British monarch. His audience throughout the text are his listeners, both at home and abroad. Until the final sentence, where the audience shifts to those huddled with him in the Pennsylvania statehouse (now Independence Hall). Jefferson turns his prose inward here. The final paragraph begins by stating: “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.” It ends with a “mutual pledge to each other.”

So where did we go wrong? Where did the political altruism of the 18th century turn into the ritual of the 21st century? It didn’t happen all at once. Nor did it occur because of singular forces. Individualism and isolation became our raison d’etre in the 20th century. In Robert Putnam’s words, we began to “bowl alone.” The Marlboro Man, a solitary figure roaming the limitless West, free from the responsibilities and, yes, from the headaches of collective action, was (and still is) idolized.

And in the theater of politics? Things are no better. Our governmental officials, especially in Congress, have in recent years sent the distinct message that entrenchment is more important than compromise, that the first principle of politics is personal survival (95 percent incumbency rate), and that working across the aisle is duplicitous. Cynicism has fully replaced faith. Jefferson’s public self would be aghast.

But, thankfully, things are not entirely hopeless. We should not despair. We can recover a morsel of the 18th century mindset with a few minor tweaks to our public behavior. Listen carefully to our politicians as they discuss their vision for the future. Is it a collective vision or one that benefits the isolated individual?

Press our political leaders on what they consider the common good. Hold our elected officials to a higher standard and don’t be afraid to throw them out of office if they fail to meet it. Require our representatives to articulate material and substantive plans for action, especially while campaigning. Insist on specifics. And on promises. And on results. And, finally, demand that they pledge their “sacred honor” to the cause of democracy. It may not work as well as it did on July 4, 1776. But it is still, all these years later, the American way.

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Trump needs to get ready for the blowback