Sarat is a ssociate provost, associate dean of the faculty and a professor of jurisprudence and political science at Amherst College.

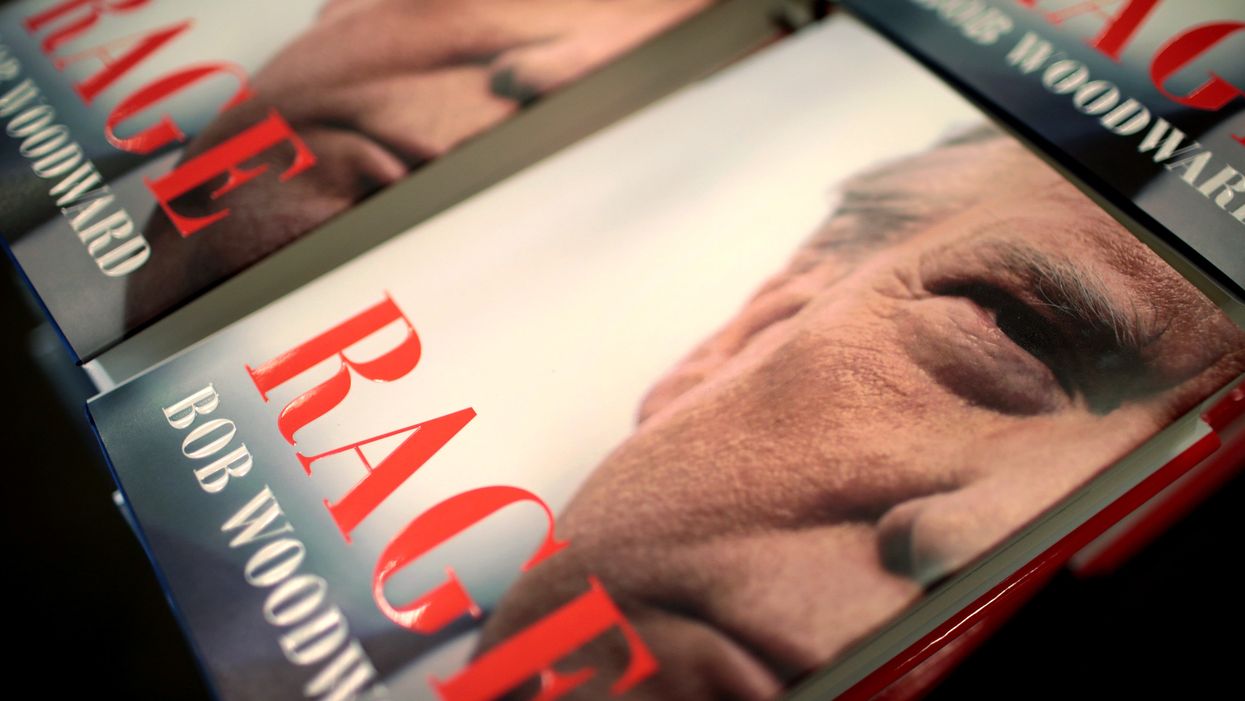

This month's revelations about how President Trump downplayed the coronavirus pandemic to journalist Bob Woodward seemed to foretell a political earthquake. Commentators and pundits argued that even for someone who lies as regularly as the president, his duplicity concerning Covid-19 was in a different and much more damaging category — with some calling it"disastrous."

Yet the earthquake has not materialized and the disaster for Trump seems to have been averted.

The Rasmussen Reports daily tracking poll of the president's approval ratings found that in the days after Sept. 8 — when news first broke about what Trump told Woodward for his new book, "Rage" — the number dipped slightly but quickly recovered. It actually improved a bit in the first two weeks of the month, from 47 percent to 51 percent. And a FiveThirtyEight polling analysis also indicates that, despite the commentariat's outrage, Trump has not paid a political price for his duplicity or its dramatic cost in American lives.

What explains this relative indifference to the revelations? And what does that indifference tell us about the state of our democracy?

Part of the explanation is specific to the Trump presidency, but part has to do with what Americans generally expect of their political leaders.

Deception and dishonesty were part of the Trump brand long before he entered politics. And since he became president Trump has succeeded in numbing the public to them.

A Quinnipiac poll in May found that 62 percent of the public did not think the president is honest. That number has not been below 52 percent since Trump took office. As Mark Mellman, a Democratic political operative puts it, "People have concluded that he's a liar. He lies every day. People know it."

It is no different when it comes to the pandemic. In July, 64 percent of the respondents to an ABC/Washington Post poll said they did not trust anything the president said about the pandemic.

Learning the president lied about the coronavirus has as much impact on many citizens as would the proverbial "dog bites man" story.

Indeed, his dishonesty is part of what some of his supporters like about him.

Trump understands that they take pleasure in his flaunting of conventional norms like honesty and truthfulness. That is why he lies so openly and brazenly.

But some explanation for why the Woodward story didn't move the needle has to do less with Trump than with Americans' general beliefs and expectations about lying in everyday life and in politics.

Research suggests that while people may praise truth-telling in the abstract, their behavior tells a different story. A 1996 study of college students found they told around two lies a day. While members of the community in which their school was located told fewer falsehoods, they nonetheless confessed to telling a lie in one of every five interactions with someone else. And a national study in 2010 concluded Americans tell an average 1.7 lies daily.

Americans lie and expect to be lied to by others. Living with deception and falsehood is just a fact of life. Some lies that we live with seem trivial, hardly worthy of note. But some are not so easily dismissed. They make a difference in business, commerce and personal relationships.

In our daily lives we reject the philosopher Immanuel Kant's injunction that lying is always morally wrong, and we appear to disregard the Biblical commandment to tell the truth. By and large, we do not regard honesty or truth telling as virtues in themselves.

Americans take a pragmatic view of lying and use it for what they regard as good causes.

What is true in private life is also true when it comes to what we expect from politicians. While surveys suggest most Americans view it as essential for people in public life to be honest and ethical, they do not believe politicians live up to that standard.

So, politics and dishonesty go together in the public mind. As a result, while Americans recognize that Trump is dishonest, they don't think he's much worse than other politicians.

Indeed, it seems Americans have a worldly, not Sunday school, view of truth and lying in politics. They recognize, as political theorist Hannah Arendt once wrote, that "truthfulness has never been counted among the political virtues, and lies have always been regarded as justifiable tools in political dealings."

Arendt understood that democracy does not depend on a world of truth. It can survive lying and liars. The test of any deception must be whether citizens, after the fact, would consider themselves better off as a result of it.

"In politics, hypocrisy and doublespeak are tools," Jonathan Rauch of the Brookings Institution declared a few years ago. "They can be used nefariously, illegally or for personal gain, as when President Richard Nixon denied Watergate complicity, but they can also be used for legitimate public purposes, such as trying to prevent a civil war, as in Lincoln's case, or trying to protect American prestige and security, as when President Dwight D. Eisenhower denied that the Soviet Union had shot down a United States spy plane."

One has to ask whether Trump's lies, which appear to have the sole purpose of benefiting himself, can be equated with those by Lincoln or Eisenhower. And one has to wonder whether his habitual lying and endless dishonesty has potentially a far more corrosive effect than his predecessors' deceptions in times of national crisis.

Democracy cannot survive and prosper if our political leaders deny that there are things that are true and things that are false — or assert that the difference between truth and falsity does not matter at all. It is endangered if leaders lie to citizens without guilt or shame.

The threat Trump poses to our democracy is not just that he tells lies, even when they are as consequential as those he told about the severity of the coronavirus, but that he lies in ways that undermine the foundations of democracy itself.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift