Norton is the Rothgerber chair in Constitutional Law at the University of Colorado Boulder.

When regular people lie, sometimes their lies are detected, sometimes they're not. Legally speaking, sometimes they're protected by the First Amendment – and sometimes not, like when they commit fraud or perjury.

But what about when government officials lie?

I take up this question in my recent book, "The Government's Speech and the Constitution." It's not that surprising that public servants lie – they are human, after all. But when an agency or official backed by the power and resources of the government tells a lie, it sometimes causes harm that only the government can inflict.

My research found that lies by government officials can violate the Constitution in several different ways, especially when those lies deprive people of their rights.

Consider, for instance, police officers who falsely tell a suspect that they have a search warrant, or falsely say that the government will take the suspect's child away if the suspect doesn't waive his or her constitutional rights to a lawyer or against self-incrimination. These lies violate constitutional protections provided in the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Amendments.

If the government jails, taxes or fines people because it disagrees with what they say, it violates the First Amendment. And under some circumstances, the government can silence dissent just as effectively through its lies that encourage employers and other third parties to punish the government's critics. During the 1950s and 1960s, for example, the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission spread damaging falsehoods to the employers, friends and neighbors of citizens who spoke out against segregation. As a federal court found decades later, the agency "harassed individuals who assisted organizations promoting desegregation or voter registration. In some instances, the commission would suggest job actions to employers, who would fire the targeted moderate or activist."

And some lawsuits have accused government officials of misrepresenting how dangerous a person was when putting them on a no-fly list. Some judges have expressed concern about whether the government's no-fly listing procedures are rigorous enough to justify restricting a person's freedom to travel.

When a person or agency backed by the power and resources of the government tells a lie, it sometimes causes harm that only the government can inflict.

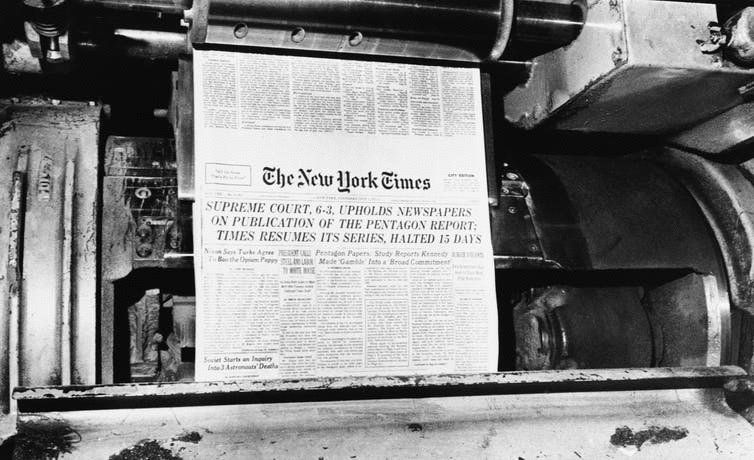

But in other situations, it can be difficult to find a direct connection between the government's speech and the loss of an individual right. Think of government officials' lies about their own misconduct, or their colleagues', to avoid political and legal accountability – like the many lies about the Vietnam War by President Lyndon Johnson's administration, as revealed by the Pentagon Papers.

Those sorts of lies are part of what I've called "the government's manufacture of doubt." These include the government's falsehoods that seek to distract the public from efforts to discover the truth. For instance, in response to growing concerns about his campaign's connections to Russia, Donald Trump claimed his predecessor that Barack Obama had wiretapped him during the campaign, even though the Department of Justice confirmed that no evidence supported that claim.

Decades earlier, in the 1950s, Sen. Joseph McCarthy sought both media attention and political gain through outrageous and often unfounded claims that contributed to a culture of fear in the country.

When public officials speak in these ways, they undermine public trust and frustrate the public's ability to hold the government accountable for its performance. But they don't necessarily violate any particular person's constitutional rights, making lawsuits challenging at best. In other words, just because the government's lies hurt us does not always mean that they violate the Constitution.

There are other important options for protecting the public from the government's lies. Whistleblowers can help uncover the government's falsehoods and other misconduct. Recall FBI Associate Director Mark Felt, Watergate's "Deep Throat"source for The Washington Post's investigation, and Army Sgt. Joseph Darby, who revealed the mistreatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. And lawmakers can enact, and lawyers can help enforce, laws that protect whistleblowers who expose government lies.

Legislatures and agencies can exercise their oversight powers to hold other government officials accountable for their lies. For example, Senate hearings led McCarthy's colleagues to formally condemn his conduct as "contrary to senatorial traditions and … ethics."

In addition, the press can seek documents and information to check the government's claims, and the public can protest and vote against those in power who lie. Public outrage over the government's lies about the war in Vietnam, for example, contributed to Johnson's 1968 decision not to seek reelection. Similarly, the public's disapproval of government officials' lies to cover up the Watergate scandal helped lead to President President Richard Nixon's 1974 resignation.

It can be hard to prevent government officials from lying, and difficult to hold them accountable when they do. But the tools available for doing just that include not only the Constitution but also persistent pushback from other government officials, the press and the people themselves.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)