America has a long, if erratic, history of expanding its democratic franchise. Over the last two centuries, “representation” grew to embrace former slaves, women, and eighteen-year-olds, while barriers to voting like literacy tests and outright intimidation declined. Except, that is, for one key group, Independents and Third-party voters- half the electorate- who still struggle to gain ballot access and exercise their authentic democratic voice.

Let’s be realistic: most third parties aren't deluding themselves about winning a single-member election, even if they had equal ballot access. “Independents” – that sprawling, 40-percent-strong coalition of diverse policy positions, people, and gripes – are too diffuse to coalesce around a single candidate. So gerrymanderers assume they will reluctantly vote for one of the two main parties. Relegating Independents to mere footnotes in the general election outcome, since they’re also systematically shut out of party primaries, where 9 out of 10 elections are determined.

Take New York City's Charter Revision Commission. Despite acknowledging that a million New Yorkers identify as independent, so cannot vote in the primary, they punted in July, declining to send an open-primary proposition to the November ballot. The excuse? Supporters hadn't reached a "clear consensus" on either the problem or the remedy.

Reformers had pinned their hopes on 2024, believing this would be the year voters finally flung open those gateways through some combination of Open-primary, Ranked-choice, or Top-X general elections (let’s call them ORT).

Alas, these efforts hit a wall. Eleven ORT proposals in nine states were on the November 5th ballot. Every single one lost.

Why? Independents and third parties don’t just want to be heard; they want a seat at the table in the room where decisions are made. They want their views rewarded. They want true representation.

Elections, at their core, are about redistributing political power. And clearly, ORT struggles to sell a polarized and skeptical public on its benefits.

RCV and Open Primaries/Top-X, despite their vocal proponents, are burdened with a litany of well-documented flaws, like exhausted ballots, strategic voting, complexity, and perverse outcomes. Linking them together on a single vote, as we just witnessed, only diminishes their combined prospects.

Why else did ORT fail at the polls? Logically, many independents understand their third-choice ranked ballot might tip the scales towards an acceptable, if uninspiring, candidate. They might even take intellectual pridein playing kingmaker.

However, RCV falls short on both the emotional and utilitarian litmus tests.

Did the eventual winner make explicit policy commitments to independents for their support– commitments they'll honor in office? Or were independents taken for granted, a default vote in the ORT system? Were third-party candidates even listed on the general election Top-X ballot? If not, a third party feels erased from history.

For a major party member, the situation is more favorable. Backing the winner brings tangible emotional and political benefits, reinforcing their social group's standing in both primary and general elections. But in ORT elections, where your leading candidate is squeezed off the ballot, you feel marginalized and demeaned.

Negotiated Consensus: A Different Approach

Voting method experimentation stretches back millennia, and while history may not repeat itself, it often rhymes. So, is there a better alternative waiting to be unearthed from the archives that might be attractive to the sidelined forty percent?

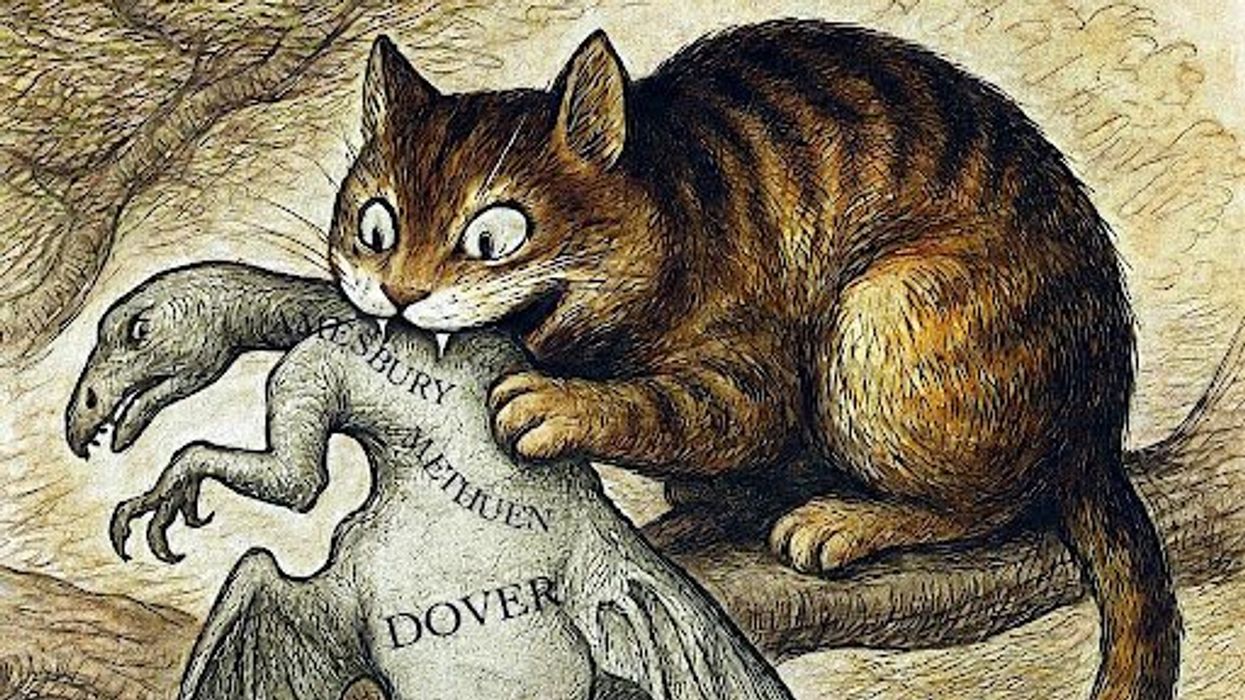

In 1885, Charles Dodgson—yes, the mathematician and author of Alice in Wonderland—grappled with precisely this challenge after discovering issues with a new preferential voting system. His remarkable suggestion? To "club" and trade votes. It’s a proposal I’ve expanded upon and call “Negotiated Consensus.”

Under Negotiated Consensus, all major candidates are listed on the primary and general election ballots. Voters cast a single vote for the nominee they enthusiastically endorse and trust as their proxy. If no candidate secures a simple majority, aspirants negotiate among themselves (and in consultation with their supporters) for policy concessions, redistributing (or “clubbing”) their proxy votes until a majority winner emerges. If a clean majority can't be negotiated, the race defaults to a top-two runoff (details can be found in the original article).

The public debate and the inherent tension of a plurality election highlight the critical role small parties and independents play as "kingmakers." Trading votes for policy concessions ensures the winner’s administration is more representative than in a plurality election or RCV, all the while sidestepping ORT's pathologies. Indeed, drawing two-party gerrymandered districts may backfire when independents shift the balance of power.

By marrying the clarity of a single-choice ballot with the accountability of public coalition-building, NC can succeed where RCV and non-partisan primaries stumbled. It promises to give independents and third parties the influence and spotlight they’ve been seeking—and in the process, revitalize majority rule itself.

Greg Blonder is a scientist, entrepreneur, and educator active in the voting rights space.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift