LaRue is former deputy director of the Eisenhower Institute, a nonpartisan think tank at Gettysburg College, and of the American Society of International Law. He adapted this piece from an article he wrote in 2018 for the Election Law Journal.

Getting reelected is becoming too easy for our presidents. Nine of the last 12 incumbents who sought a second term, including four of the last five, succeeded. A re-elected President Trump would make it four in a row.

The structure of maximum presidential service — eight years in two equal terms — strengthens this probability. Every incumbent has an advantage in pursuing reelection. And reelection itself is not a bad thing. But its timing at four years has become so unfair that I call it the "four-year crutch."

This crutch consists of a fluid mix of factors that boost each incumbent differently. Extensive public exposure and access to institutional resources support their candidacies. And myriad other factors lessen public interest in ousting them after four years: the permanent campaign, partisan hype, media bias, disinformation, voter fatigue — even the Electoral College skewing the value of millions of votes.

Voters give the incumbent the benefit of the doubt or see him as the better devil because he is known. Nonvoters are given reasons or find excuses to ignore their civic duty, or they are impeded from exercising it. (And they outnumbered Trump's 63 million voters in 2016 by 31 million.)

The four-year crutch is real, but also ephemeral. The electoral rhythm after a president's first wins is predictable: Pushback at two years, re-election at four and repudiation at six. Political commentator Kevin Phillips back in1984 labeled the phenomenon of the public souring on presidents they just re-elected as the "six-year itch," a valid term to this day. Such repudiation, however, does not stand alone; it extends to year eight, when lame-duck challenges and a nation's heightened desire for change weigh heavily against a would-be successor from the incumbent party.

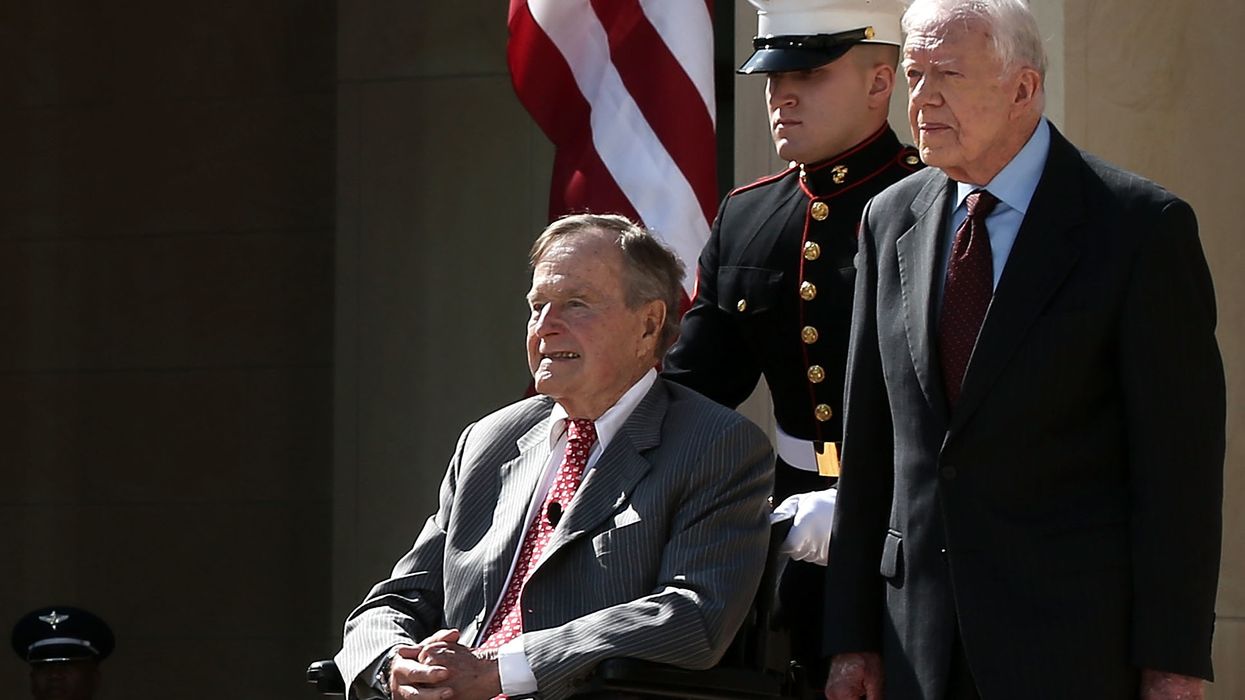

These dynamics have produced an extraordinary record. From 1952 through 2016, Republicans and Democrats have taken eight-year turns in the White House with just two exceptions: A four-year interregnum for Democrat Jimmy Carter followed by a dozen straight GOP years under Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

To be sure, defining trends in presidential elections over time is highly problematic, because the factors affecting each contest vary widely, change every election and differ in intensity.

But two patterns have held. First, after eight years of one party's service in the White House, the voters — or, more accurately, Electoral College electors — usually turn to the candidate of the other party. Second, when this candidate prevails, he is almost never rejected after just one term. Carter is the one exception, going back to the 19th century. Trump could still give Carter some company, but the four-year crutch makes his path to victory easier than his opponent's.

Fundamentally, re-election after four years is too soon for the American psyche.

The timetable is set by the Constitution, so altering it would require an amendment — seemingly impossible today. Still, different presidential term lengths merit consideration. A six-year first term and three-year second term could work particularly well. (Requisite electoral synchronicity would occur by making House terms three years and adjusting Senate elections to be for half the body every three years; a three-year election cycle would result.)

Re-election or rejection at six years would align better with the public's proven inclination to exercise a more demanding electoral voice at that time. Such a structure also would value presidential terms more accurately. Second terms may not be cursed, but their increasingly diminished contributions should not be valued the same — by length — as first terms.

The additional benefits are compelling: A six-year initial term would be long enough to address a president's top objectives; a three-year second term would be more like a bonus and less automatically pursued; winning re-election during a six-year itch would mean a stronger second-term mandate; the president would be a lame duck for only a third (not half) of his or her time in office; the system would provide a bit of a break from the permanent campaign.

And, importantly, single-term presidents would not necessarily be considered failures and we'd see more of them.

The main concern would be enduring two extra years of a poorly performing incumbent. But this risk is offset because we have also re-elected presidents after four years who likely would not have prevailed two years later. (George W. Bush comes to mind.) If Trump wins this fall, might his opponents have preferred the greater likelihood of defeating him in 2022 — resulting in two fewer years of his service?

Amending the Constitution is even harder to contemplate when the ideals beneath it are under attack, while the electoral institutions and processes above it are in disarray. Election reform is a very crowded field: presidential nomination processes are dysfunctional, voting rights are threatened, campaign spending is out of control and our principal voting method — plurality winner-take-all — is both polarizing and non-majoritarian.

Still, we ignore our eroding electoral infrastructure at considerable risk. The disappearance of the single-term presidency could prove to be a leading indicator of growing structural weakness in our democracy. More two-term presidencies and more diminished second terms are likely to reveal increasingly serious faults with the system now.

We must regain our ability to repair the document that anchors America's civic life before its cracks spread too far. Changing the Constitution to alter the presidential election timetable, and with it executive branch's powers, is a fine place to start.