Patricia Guevara enjoys doing things with her 5-year-old daughter, Miranda, especially painting and drawing and taking an occasional walk in the park.

After a promotora, or community health worker, stopped by their Pittsburgh-area home, their lives became more active.

Guevara signed up for a promotora-led program for Latino preschoolers and their families. Through the home-based pilot program, University of Pittsburgh researchers sought to study how community health workers affected physical activity among Latino families with young children.

“I thought it was great because we made a commitment to be physically active at least five days a week,” said Guevara, who moved to Pennsylvania from Venezuela seven years ago.

Patricia Guevara with her husband, Victor, and their daughter, Miranda. A visit from a promotora has helped them stay more active. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Guevara)

Patricia Guevara with her husband, Victor, and their daughter, Miranda. A visit from a promotora has helped them stay more active. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Guevara)Promotores, the gender-neutral Spanish term for community health workers, work as liaisons between communities and public health and social services to narrow gaps in health equity. The promotores typically share language and ethnicity with the people with whom they work. Their role is to raise awareness and teach participants how to access health services and other programs.

“We look like them, we talk like them and we’re a part of their community,” said Mercedes Cruz-Ruiz, a longtime promotora who trains community health workers through her organization in Fort Worth, Texas. “We build long-term relationships in our community.”

Community health workers have long disseminated basic health education in various countries. In China, early promoters of preventive health were trained farmworkers doing outreach in agricultural fields in the 1950s and 1960s. The concept spread globally, and by the 1970s, it became part of efforts to reach rural and low-income communities in the United States.

Spanish-speaking promotores have become essential in Latino communities – one of the fastest-growing populations in the U.S. – in recent years. A 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report found that Hispanic people had disproportionately higher death rates from some health conditions, including diabetes, and a higher prevalence of obesity and uncontrolled high blood pressure – all of which can contribute to heart disease. Hispanic people make up nearly 20% of the U.S. population, but they also have the highest uninsured rate of any racial or ethnic group, census data shows.

Promotores receive specialized training in health education and typically work under the guidance of nonprofits, health care centers and other organizations, many as volunteers. Federal policies also help to fund the work of promotores through grants, state programs, Medicaid reimbursement and other social service programs.

In Pittsburgh, the university, local government and community groups use promotores to help the area’s Hispanic population. In Allegheny County, more than 30,000 Hispanic residents make up 2.5% of the population, census data shows. Many of them live in Pittsburgh, where the Hispanic community grew from nearly 7,000 in 2010 to more than 10,000 by 2021. Pennsylvania’s Hispanic population is the state’s third-largest racial or ethnic group, at about 8%. It surpassed 1 million in 2020, up about 45% from 2010.

Dr. Patricia Documet, an associate professor in behavioral and community health sciences at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Public Health, said the city’s growing Latino population includes a mix of people with roots in various Spanish-speaking countries. Documet, a pediatrician from Peru, said that when she arrived in Pittsburgh during the 1990s, programs were lacking for Hispanic residents, but local government and community organizations have slowly begun to address their needs.

Much of her current research focuses on the impact of social support on the health of Latino people and of community health workers promoting access to health care services, healthy eating and exercise among families. She works with the Latino Engagement Group for Salud, a coalition of community groups working with promotores and other Latino people on community-focused initiatives, such as De la Mano con la Salud (Lend a Hand to Health). The project trained male promotores to help connect Latino immigrant men with health and social services.

“Promotores help the participants attain their own goals,” Documet said. “That works better than telling people what to do.”

In Texas, where roughly 40% of the population is Hispanic, Cruz-Ruiz’s desire to work as a promotora grew out of her own experience. She’s a survivor of mini-strokes, and both her parents had heart disease. At 44, her father died of a heart attack. Cruz-Ruiz knew she was at high risk, so she learned about heart disease. She believes sharing that knowledge could help others prevent chronic illnesses.

The length and training for promotores can vary, depending on the health issues they learn about, Cruz-Ruiz said. Once completed, they go out into their communities to take people’s blood pressure, show them how to take their medication, provide a ride to a doctor’s appointment or share information on programs for healthier living.

“If we can do prevention ahead of time, we can slow down chronic disease,” she said. “A health care provider may have 10 minutes to talk to a person, but a community health worker, we can talk to them for an hour and really explain what’s going on in their body.”

Guevara said she and Miranda liked the frequent interaction in their own home with a promotora who spoke Spanish. “The first day the promotora came to our house, she brought us a box with guides and games for physical activity,” she said.

Miranda Guevara, 5 years old, loves to paint. She also likes to go to the park where she can play with her family and be more active. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Guevara)

Miranda Guevara, 5 years old, loves to paint. She also likes to go to the park where she can play with her family and be more active. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Guevara)The promotora has helped them stick to their commitment to be more active for the past two years, Guevara said.

“My daughter learned that exercise is necessary and helps us stay healthy and have better energy to be active,” she said. “To this day, my daughter still asks to be physically active.”

Promotores create a bridge between healthier living and a growing Hispanic population was originally published by The American Heart Association and is republished with permission.

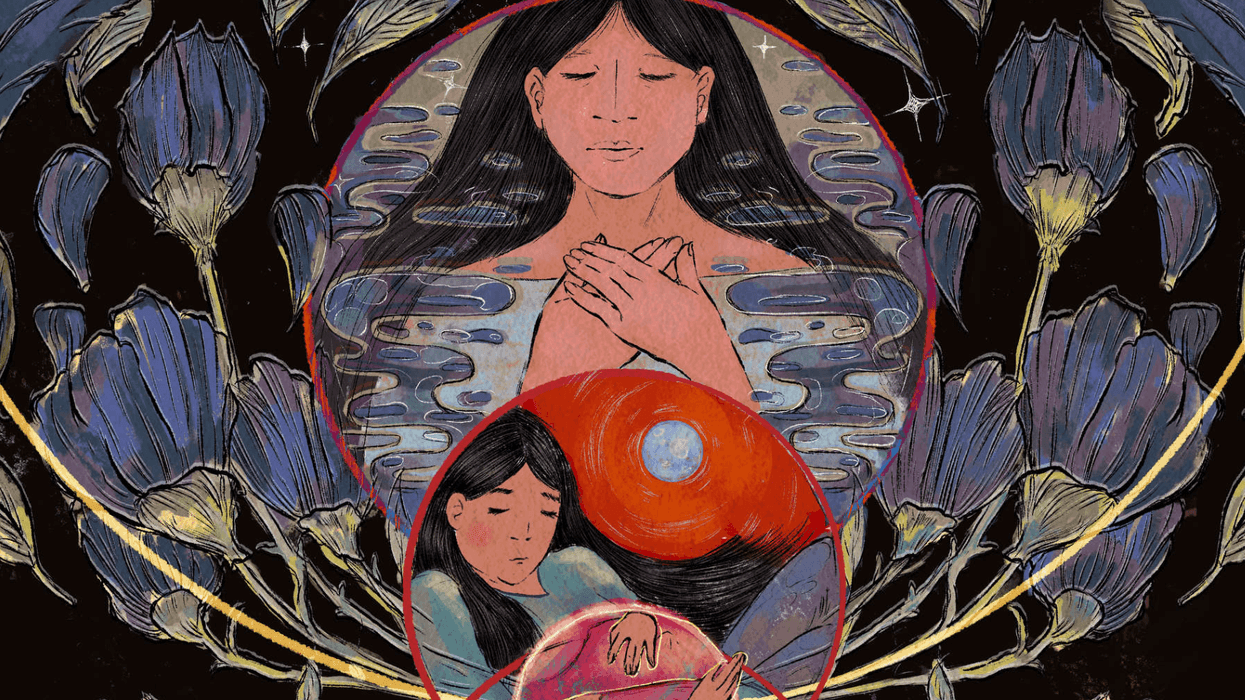

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift