WASHINGTON — Health care administrators across rural America say financial pressures are mounting as federal support programs expire and Medicaid cuts take effect, putting many facilities at risk of closure.

In Hugo, Colorado — a town of fewer than 1,000 people — that reality is familiar. Lincoln Health, a 25-bed hospital and the only facility on the nearly 600-mile stretch of I-70 between Denver and Kansas City, Missouri, has faced financial strain for years.

“If you drive east on I-70, you care about my hospital because I'm the only thing out here if something should happen,” said Kevin Stansbury, Lincoln Health’s CEO. “We do a lot, and we do it not because any of those things are terribly lucrative. We do it because there’s no one else out here to do those things.”

Last month, Lincoln Health closed its assisted living facility due to financial constraints. Stansbury said the hospital is still evaluating how to maintain its remaining services as Medicaid cuts hit and key federal programs expire.

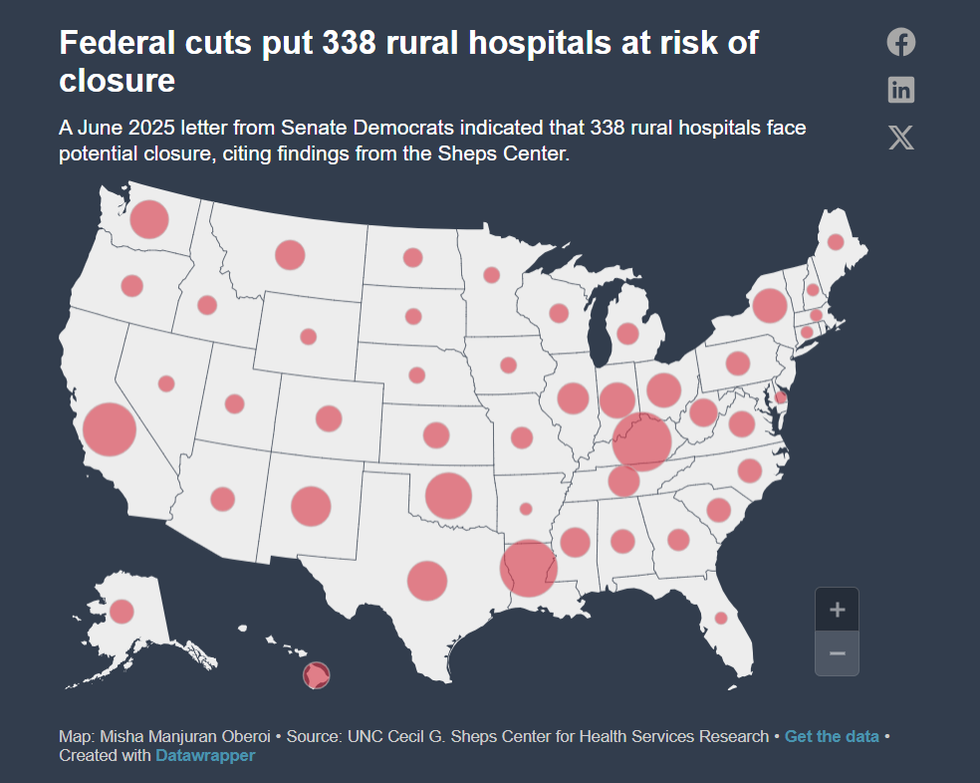

The federal reconciliation bill, signed into law on July 4, is projected to cut federal Medicaid spending by $911 billion over the next decade and increase the number of uninsured Americans by 10 million, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The reductions are set to take effect over the next two years.

In rural areas, federal Medicaid spending is projected to decline by $137 billion over the next decade, according to estimates from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Roughly three-quarters of Lincoln Health’s patients are covered by Medicaid or Medicare, and even before the cuts, reimbursement rates were low, Stansbury said.

Several federal programs that offered financial support to rural hospitals lapsed on September 30, including the Medicare-Dependent Hospital program, which provided enhanced payments to hospitals with a high proportion of Medicare patients, and the Low-Volume Adjustment program, which offered additional payments to hospitals with low annual discharges.

The Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital program, which offsets uncompensated care costs for hospitals serving a high number of Medicaid and uninsured patients, saw $8 billion in cuts on October 1.

“Not knowing whether those payment adjustments will continue is incredibly difficult for hospital administrators to be able to plan long term because they don't know whether or not they will continue receiving those payments,” Alexa McKinley Abel, director of government affairs & policy at the National Rural Health Association, said.

Abel added that many hospitals have already been budgeting under the assumption that the cuts will remain in place.

Roughly half of the nation’s rural hospitals currently operate at a loss, according to the National Rural Health Association. Stansbury described challenges that Lincoln Health shares with many rural hospitals, including low commercial reimbursement rates and limited access to capital.

A study by the Colorado Rural Health Center found that rural eastern hospitals receive commercial payments averaging 139% of Medicare rates, compared with 240% in Denver.

“They’re just going to try to drive me as low as they possibly can,” Stansbury said. “And what it seems to be forgetting is that if I go out of business, then there’s a big area of the state that doesn’t have health care.”Moreover, built in 1959, Lincoln Health has had limited resources for major renovations. Operating on tight margins leaves little room for upgrades or construction, he said.

In some rural areas, maternity care is estimated to be the first to shut down due to its high operating costs, according to Denae Herbert of the Louisiana Rural Health Association.

“There's not sufficient volume to really sustain a birthing center,” Herbert said. “So if there is a rural hospital still providing that service, that would certainly be at risk as well, which is very concerning, particularly because of the maternal mortality rate in Louisiana being as high as it is, we need to increase access to maternal health care, not decrease it.”

According to a 2024 report by the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, 75% of rural hospitals in Louisiana don’t offer maternal care. The state’s maternal mortality rate stands at 37.3 deaths per 100,000 live births — among the highest in the country.

A June letter from Senate Democrats estimated that 33 rural hospitals in Louisiana are at risk of closing following the cuts.

DATA VIZMisha Manjuran Oberoi i

DATA VIZMisha Manjuran Oberoi i

In Virginia, that number amounts to six. But according to Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.), these hospitals are concentrated in areas that voted overwhelmingly for President Donald Trump.

“The irony of this is that these were the communities that frankly — they voted for Trump because they wanted to lower costs,” Warner said. “Well, we've not seen groceries go down, we've not seen inflation go down, and states are seeing health care costs skyrocket.”

Lee County Community Hospital, one of the six at risk of closing under the cuts, is part of a county that voted 85.7% for Trump, according to Politico’s election map.

The situation in Oregon is similar, according to Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.). He said he recently led a series of town hall meetings in rural Oregon, in communities that voted 70% for Trump. He said people are aware that a “health care wrecking ball is coming right at them.”

Wyden also echoed Herbert’s concerns about the potential increase in maternity deserts nationwide.

“You can't have rural life without rural health care, but we are headed in that direction,” Wyden said.

While inpatient rural hospital care is facing setbacks, so is virtual care. The telehealth waiver enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic expired on Oct. 1. In most cases, providers will no longer be reimbursed for telehealth visits delivered to Medicare patients in their homes.

Abel said this is a major concern because telehealth has the potential to improve rural health care significantly. She said a longer extension of the flexibilities would have been beneficial for rural areas.

“There's been studies showing that uptake in rural areas for telehealth has actually been less compared to in urban areas, and I think that's because the infrastructure is not fully there yet, and without knowing that these flexibilities will be in place for the long term, it's hard for providers to invest in it,” Abel said.

Stansbury says that while telehealth is an additional challenge, it is not a substitute for in-person care.

“If somebody gets in an automobile accident on I-70, telemedicine does nothing for that,” he said. “I need people on the ground who are able to receive those patients and take care of them effectively.”

For patients who rely on these hospitals daily, the combination of aging facilities and policy changes is tangible. Limon, Colorado resident Lorie Coonts has been using Lincoln Health’s services for four decades. Despite the hospital’s deteriorating condition, including shared bathrooms and the absence of OB-GYN services, Coonts said the hospital is like “family taking care of family.”

She said she worries about the hospital’s financial instability and risk of closure, noting that if Lincoln Health were to close, the small community would dwindle further.

“It just feels like the hospitals are faced with one thing and one after the other,” Coonts said. “It just feels like it’s more and more mandates and rules … that just keep things from being easy and being able to afford it. Every time we turn around we get slapped in the face with something else.”

Misha Manjuran Oberoi is a junior from Noida, India, studying journalism and psychology at Northwestern University. In the past, she has written for the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle and The Mint, and was featured on WTTW Chicago. Misha enjoys reading historical nonfiction, feminist literature, and YA fantasy.

Best,

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)