Sitterley is Staff Attorney at United Stateless, an organization advocating for stateless people in the U.S.

Recent experiences of a stateless family living in Las Vegas, Nevada show how hard it can be when no country will claim you as a citizen and you have fewer safety nets when things go wrong.

There are about 218,000 stateless people living in America and there are millions of stateless people around the world, and each of them has their own story. Conflicts, wars, and other geopolitical crises around the world often leave people without a country. But there is really no such thing as a “typical” stateless case. Each one is unique, and often complex. Jay’s unique and complex story shows how organizations like United Stateless, where I work as a staff attorney, and our partners, can help.

Jay was born in South Korea to a Korean mother and Japanese father who were not married to each other. At the time of his birth in 1982, South Korean women could not pass their citizenship on to their children pursuant to the law. Gender discrimination in nationality laws is still a problem in 25 countries worldwide. Jay’s father was married to a different woman, and therefore Jay was not included in his koseki, or family registry, in Japan. The koseki is the official and legal acknowledgment of family relationships. So, Jay was not legally his father’s son according to Japan, and therefore could not access Japanese citizenship, either.

Jay's parents wanted to be together, so they came to the U.S. on tourist visas in the early 1980s. Jay was young enough to not require a passport or his own visa under the laws at the time. The family overstayed their tourist visas and Jay never left the U.S. He grew up speaking English and attended American public schools, but without any legal status. Jay made a living as a soccer coach and playing poker until he was finally able to obtain a work permit for the first time in 2012 under Deferred Action For Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

Jay ended up in Las Vegas, Nevada, and married his wife, Maria. Maria, too, had overstayed a visa having come to the U.S. from Greece. Over the next decade or so, they had two U.S. citizen children.

After a series of alarming symptoms and multiple emergency room visits, doctors diagnosed their older son with a chronic gastrointestinal disease. A specialist put the nine-year-old on medication that finally improved his symptoms. But just as the boy was getting better, the family got the news that Medicaid— the government insurance program which provides insurance for millions of low-income adults and children in the U.S.— wanted to switch the medication. But the doctors disagreed, and urged the family to keep the child on his current medication. The problem was that Medicaid would not keep covering the injection. Out of pocket, the expense could be $12,000 a month or more.

The family was faced with an impossibly unfair situation. They wanted to listen to the doctors and give their child what the specialist recommended. But there was no way they could afford to do it.

Maria’s family was still in Greece. The children could become recognized as Greek citizens because of Maria’s citizenship. As a Greek citizen, their son could access Greece’s universal healthcare. And it seemed clear that Jay would be able to obtain legal status and eventually Greek citizenship as well, because of his marriage to a Greek citizen. The family made the decision to move to Greece. Without legal status or affordable healthcare in the United States, it made sense to move.

The problem was that Jay is stateless; a citizen of nowhere. He had no ability to obtain a passport. Even though he could apply for legal status in Greece, he had to physically get there. You can’t board a plane without a travel document. You can’t pass through customs without proving who you are and where you come from.

Then the situation became a race against time. Medicaid informed the family that coverage for the medication would end in July, 2023. Jay began reaching out to organizations like United Stateless to see if there was a way for him to get to Greece without a passport. As we scrambled to find a solution, time ran out, and Maria and the children had to go to Greece without Jay. At the time, there was no guarantee that Jay would ever get to Greece to see his family again. And as a visa overstay, it was likely that Maria could never legally return to the U.S. The anxiety of family separation is horrific.

United Stateless worked with Jay to try to get him across the ocean and into Greece. We advocated directly to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). We also coordinated with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The ICRC issues a so-called "emergency travel document" for highly specific humanitarian purposes. It is not a passport or a free travel document. It is a document that allows a person to exit one country and enter another exactly once for a small window of time. There is no travel back and forth. Some countries don't even recognize it because ICRC is an international non governmental organization rather than a sovereign state. Requesting the emergency travel document took a lot of diplomacy behind the scenes. The ICRC has strict requirements for issuing the document. One of which was for Greece to say they would admit Jay with the ICRC travel document. But that is chicken-and-egg. Greece was reluctant to provide any statement about admission for a person who was not in possession of a travel document. And any application for an entry visa required a travel document number for the application to even be submitted.

ICRC also needed to see that Jay had no other option for a travel document from any other entity. Jay did much of this exhausting work himself. He was on the phone with consulates. He sent emails. He phoned ministers of foreign affairs. He flew around the U.S. from Las Vegas to Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. He went wherever he could get a meeting.

With some of the responses from the Japanese and South Korean consulates, as well as other research into relevant nationality laws, we finally convinced ICRC of Jay's statelessness. Those authorities issued statements saying he is not entitled to a passport from their respective countries. We got documentary evidence from the European Council and statements from UNHCR that Greece was likely to accept the ICRC travel document and that there were known cases of Greece doing so in the past. However, there was still the issue of the entry permission—a separate inquiry from whether the ICRC document was valid for travel.

Greece refused to assure the ICRC that it would admit Jay. And it didn’t help that employees in Greece, like much of Europe, are largely on vacation during the month of August. So, finally, Jay showed up at the ICRC headquarters in Washington, D.C. in person. He begged them to give him the document and let him try to go to Greece without a visa. He showed them we had tried everything to get a meeting, but nobody had been willing to say in advance that they would let Jay into Greece. There was a real risk that if he tried to enter, he could be detained - perhaps indefinitely. Finally, Jay was able to convince the ICRC representatives he would be worse off if he stayed in the U.S.

That's because he was about to lose his valid photo identification in America. His status was expiring under DACA at the end of August, and his state-issued ID was also tied to that expiration date. It also meant he would be vulnerable to immigration enforcement in the U.S. Even if he went to Greece and got put into detention and deportation proceedings he would be better off. As long as he got to Greece, they couldn’t deport him because no country would accept him—not even the United States. Jay’s dedication to his family and tenacity in removing all obstacles to seeing his children again was a force to behold. He was steadfast that he would rather be in detention in the same country as his family than free without them. At last, ICRC agreed to let him try. In the last days of August, they issued the emergency travel document which allowed him to board the plane to Greece.

Because Jay did a lot of knocking on doors, he finally convinced people to give him a chance. When he arrived in Greece, customs authorities accepted the ICRC travel document and admitted him as the spouse of a Greek citizen without requiring an entry visa. Now he is applying for citizenship in Greece and has started work as a soccer coach. His son is getting the medicine he needs. He has "made it." Although, he can likely never return to America. Jay said often how helpful United Stateless was in getting him to Greece and reuniting him with his family. I spoke with him on the phone at least twice a day in the weeks leading up to his departure. After he arrived safely, he sent me a photo of his two kids playing in their new backyard in Greece. It was a beautiful image.

The bottom line is that Jay and his family were lucky. Statelessness divides families and forces them to make desperate choices. Jay has had to leave the U.S. for good, despite having spent his entire life here. His two children, who are U.S. citizens, are unlikely to return to this country either. The sacrifice is huge.

Recently, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued new guidance on statelessness. It said its office will define statelessness, and that it can be a factor in decisions on certain immigration applications. But for families like Jay's, the slow turning of the wheels didn't help. In the end, the U.S. can do more to help families like Jay's. By reintroducing and passing the Stateless Protection Act we can enshrine these things into law. The specific protections offered by this bill would allow stateless people access to travel documents for international travel. No family should be in a position like Jay's was. In the end, his last move to Greece was like waiting to see the last card in a hand of poker and see if he had won or lost. Such a card is called “the river” in poker, Jay says. But America can do better than sell people down the river on these issues.

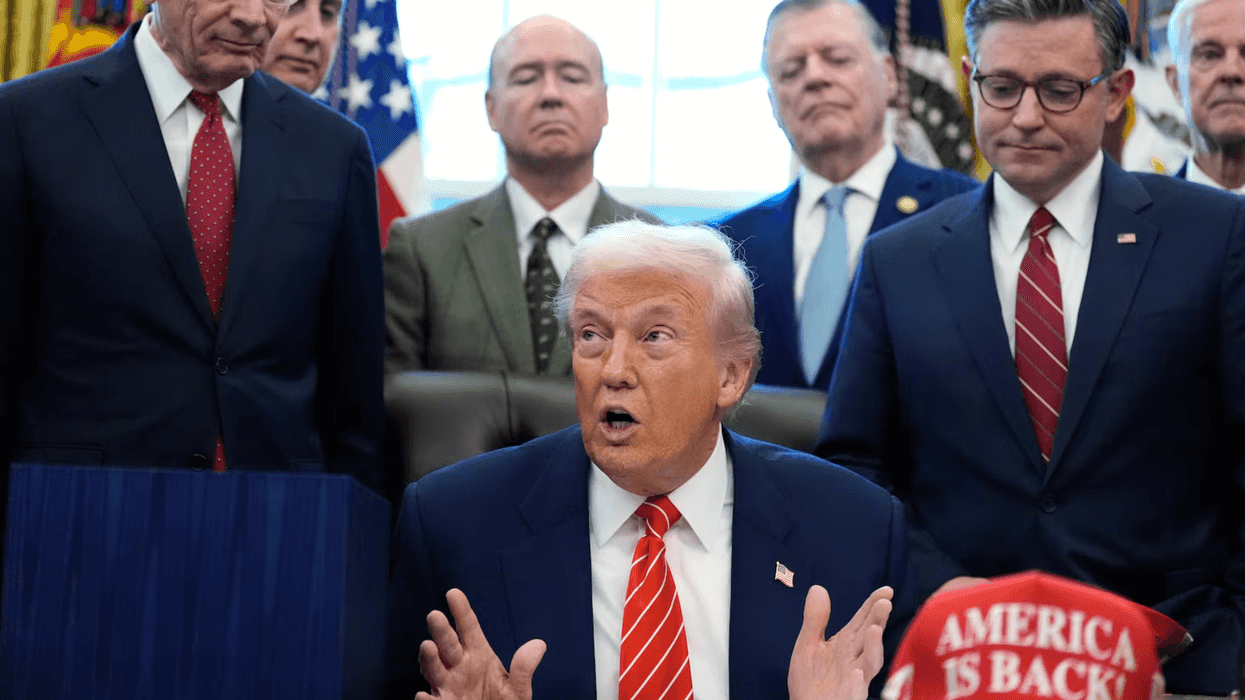

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift