Olson is the Democracy & Bridgebuilding Program Manager with Interfaith America.

Heather and Jack instantly bonded over their shared blue hair, but besides a similar taste in hair dye, they had little else in common—other than their desire to avoid a jail sentence.

For over 45 years as a DC-based public defender, Heather Shaner has tirelessly protected vulnerable clients from judicial system abuse. “The older I get, the more I think that prisons should be torn down, and very few people should go to jail,” she reflects, underscoring her role to “stand between the overwhelming power of the United States of America and the individual.” Her career took an unexpected turn when she was asked to represent January 6th rioters—fervent Trump supporters like Jack Griffith. Shaner’s decision to defend these individuals, despite facing criticism, was an opportunity to show that empathy and accountability are not only compatible but essential for justice, even for those society might condemn.

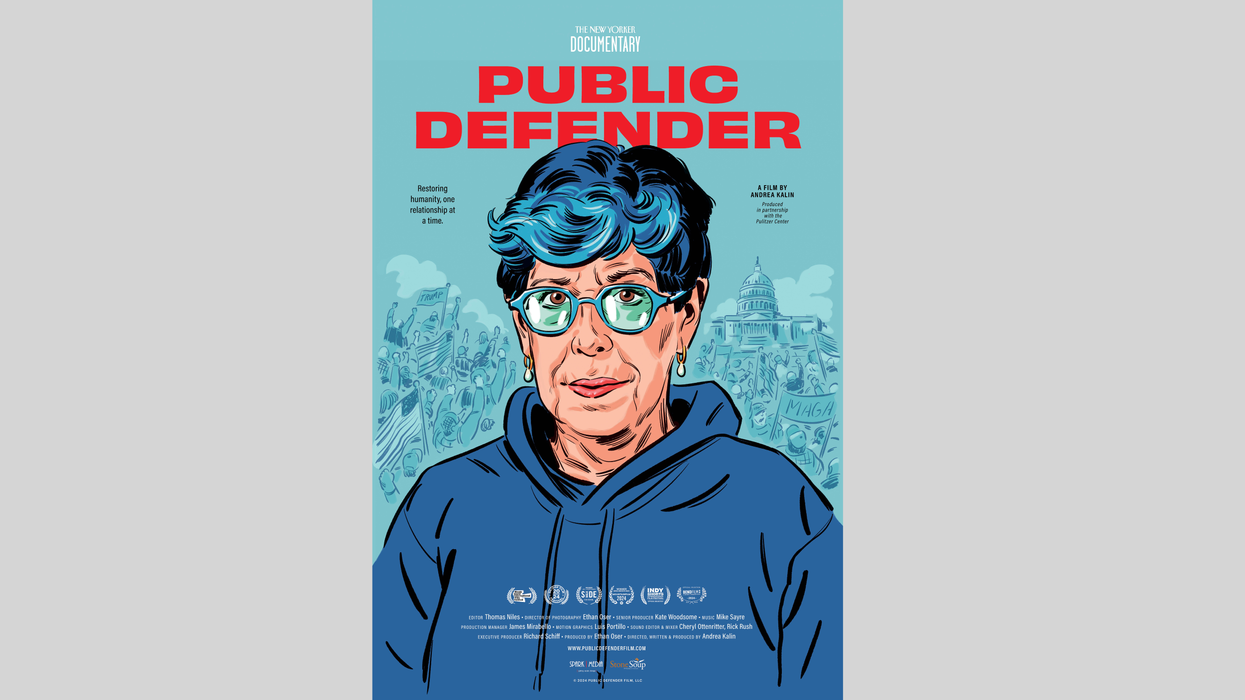

When filmmaker Andrea Kalin first read about Shaner’s novel approach toward her January 6th defendants—sending them books to help them reflect on their motivations—she saw a story worth exploring. This encounter led to the creation of Public Defender, a documentary now streaming on The New Yorker, which follows Shaner as she represents two clients: Jack Griffith, a boisterous social media personality from Gallatin, Tennessee, known as “Liberty Dragon,” and Annie Howell, a single mother from Hanover Township, NJ.

Heather Shaner (left) shakes hands with her client and Jan. 6 defendant Jack Griffith (right) Spark Media

Heather Shaner (left) shakes hands with her client and Jan. 6 defendant Jack Griffith (right) Spark Media

The documentary doesn’t offer easy answers, nor does it suggest that every participant in January 6th will experience a dramatic change of heart. From the beginning, Jack and Annie approach their involvement in the Capitol events with starkly different attitudes, though neither of them were physically violent or vandalized property. Jack remains firm in his beliefs in a stolen election, while Annie struggles with personal turmoil and a feeling of betrayal from disinformation. Shaner’s work with them leads to personal journeys that evolve as the film unfolds. The complexity of their responses reflects the broader challenge of addressing the divisions that still shake our country.

Shaner, an unabashed progressive (her home even displays a framed “F*** Trump” poster), has now taken on 42 clients charged for their actions on January 6th—many of whom sit on the far opposite end of the political spectrum than she. By radically listening to their story and acknowledging their hurt, skipping the preaching, and trusting them to grow— Shaner offers an encouraging example of how we can bridge intractable divides. These divides, left unaddressed, continue to threaten our democracy and national security.

At a recent screening at the Dialogue Film Festival in Milwaukee, I saw firsthand how Public Defender ’s fresh perspective resonated with the audience. Based solely on the film's subject matter, it would be easy to expect grim footage of the Capitol riot, fast-paced legal jargon, and disturbing rhetoric from the insurrectionists. Yet Kalin’s film takes a different route—centering relationships with sincerity and even moments of levity. It invites viewers to wrestle with their own capacity for contempt and the limits of their belief in redemption.

As Arthur Brooks wrote in Love Your Enemies, “If we want more unity and less contempt, however, we need to get out of our comfort zones, go where we are not welcome, and spend time talking and interacting with people with whom we disagree—not on lightweight stuff like sports and food, but on hard moral things” Kalin’s documentary challenges us to break the cycle of political hate and division, not by absolving wrongdoers, but by fostering understanding and rejecting the simplistic caricatures we often impose on those we disagree with.

In partnership with Interfaith America, Stone Soup Productions, is showing Public Defender in communities across the country, accompanied by regional book drives for prison libraries. These screenings, and the post-film Q&A, aim to spark dialogue about political radicalization, with new framing that every person who stormed the Capitol has a unique story. “If 2,500 people went in,” Shaner reflects, “that’s 2,500 stories.”

While faith isn’t the central theme of Public Defender, it subtly informs much of Shaner’s approach. In one intimate scene, as Shaner sits in her kitchen, the camera pans to a painted ceramic Hamsa hung on her wall as she quotes a Talmudic verse, almost as if humbly reassuring herself of her mission: "If you save one life, you’ve saved the world.” She continues by saying “You can only change one life at a time, so there's a lot of work to be done”.

Less than a month before election day, when our political climate feels eerily reminiscent of four years ago, Public Defender reminds us that America’s political divide requires more than just election victories and defeats to heal. Healing requires compassion, accountability, and a willingness to seek humanity in those with whom we fundamentally disagree. By focusing on the individual stories behind the political movement that perpetrated the Big Lie, there is hope to be found, even if it’s messy.

You can watch Public Defender on The New Yorker's YouTube channel:

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

Public Defender, a 40-minute documentary, is now streaming on The New Yorker. Stone Soup Productions is a Faith in Elections Playbook Grantee, an initiative co-created by Interfaith America and Protect Democracy to help communities bridge divides caused by polarization and protect free and fair elections.

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ranking member Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) (R) questions witnesses during a hearing in the Russell Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill on February 10, 2026 in Washington, DC. The hearing explored the proposed $3.5 billion acquisition of Tegna Inc. by Nexstar Media Group, which would create the largest regional TV station operator in the United States. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ranking member Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) (R) questions witnesses during a hearing in the Russell Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill on February 10, 2026 in Washington, DC. The hearing explored the proposed $3.5 billion acquisition of Tegna Inc. by Nexstar Media Group, which would create the largest regional TV station operator in the United States. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)