The New Georgia Project is a nonpartisan effort tot register and civically engage Georgians. Georgia's population is growing and becoming increasingly diverse. Over the past decade, the population of Georgia increased 18%. The New American Majority – people of color, those 18 to 29 years of age, and unmarried women – is a significant part of that growth. The New American Majority makes up 62% of the voting age population in Georgia, but they are only 53% of registered voters.

Site Navigation

Search

Latest Stories

Join a growing community committed to civic renewal.

Subscribe to The Fulcrum and be part of the conversation.

Top Stories

Latest news

Read More

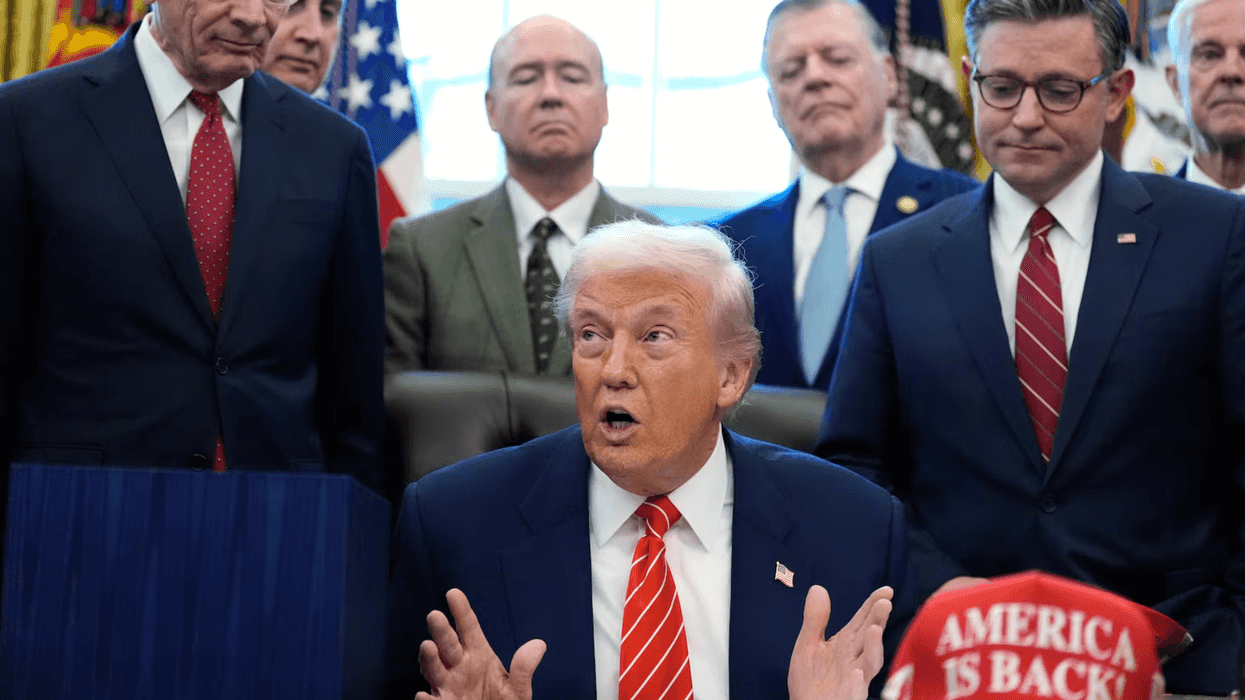

President Donald Trump speaks in the Oval Office of the White House, Tuesday, Feb. 3, 2026, in Washington, before signing a spending bill that will end a partial shutdown of the federal government.

Alex Brandon, Associated Press

Trump Signs Substantial Foreign Aid Bill. Why? Maybe Kindness Was a Factor

Feb 25, 2026

Sometimes, friendship and kindness accomplish much more than threats and insults.

Even in today’s Washington.

When Washington ended its most recent partial shutdown this week, President Donald Trump signed budget bills that contained substantial foreign aid appropriations, including $9.4 billion for global health programs.

This was much more than the president had originally indicated. It came about a year after Elon Musk’s DOGE cuts eviscerated the United States Agency for International Development and after disparaging remarks about foreign aid floated through many political discussions.

And it vindicated much of what Sam Daley-Harris has been trying to do for years.

I’ve written about Daley-Harris before. He’s an advocate, the founder of Results, an aptly named group that concerns itself with people who are poor. But unlike most advocates, he has pioneered a method that trains volunteers on how to develop cordial personal relationships with their local members of Congress. He calls it “transformational advocacy,” and he believes it played a role in these appropriations.

The $9.4 billion is less than the $12.4 billion appropriated last year but much more than had been anticipated. It is part of a $51.4 billion foreign aid package.

Daley-Harris believes a lot of people want to make a difference in the world but don’t know how to do it. Should they protest? Should they file lawsuits?

“I think so few people know the transformational advocacy route; the build-a-relationship route,” he told me last week in a Zoom interview.

Daley-Harris learned years ago that good ideas alone aren’t enough to move the needle in Washington. Most advocacy organizations ask their volunteers to sign petitions or cookie-cutter form letters. It makes them feel as if they’ve done something even though Daley-Harris says only 3% of congressional staffers say those methods are effective.

Instead, he teaches volunteers how to become confident enough to meet with their own representatives in Congress or to access the editorial boards of their local newspapers. Instead of filling in form letters, they write their own op-eds.

If the member of Congress isn’t interested, the volunteers are taught to politely ask, “What would it take to change your mind?” Then, “Could you say more about that?” And finally, “Why do you think that is?”

Important letters

Over time, these everyday volunteers build relationships. Those relationships, Daley-Harris believes, eventually led to the letters hundreds of lawmakers of both parties signed recently urging the heads of important subcommittees to approve the funding that ended up in the budget bills President Donald Trump signed.

Those letters included the types of easily verifiable things Results volunteers have told members of Congress about for years, such as how the Global Fund for AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria has lowered HIV transmission rates by 75%, or how U.S. foreign assistance has, since 2000, reduced the number of preventable deaths to children under 5 by 58% and maternal mortality by 42%.

Did Trump know what he was signing? Did the larger issues that had divided Washington obscure the relatively small amounts for foreign aid and health programs?

Hard to say, but foreign aid traditionally has made up 1% or less of the federal budget.

Daley-Harris said he’s sure that of the hundreds of representatives who signed letters, “very few of them had ever heard of these things when they were running for Congress the very first time.” His “transformational advocacy” has informed them.

As always when I write about Results, I have to acknowledge that the organization gave me an award 15 years ago for my reporting on global poverty. Results leaders have connected me numerous times with Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel Peace Prize winner and current interim leader of Bangladesh. Last year, I traveled to Bangladesh to meet with him, eventually writing a five-part series on his efforts to lift thousands in that country out of poverty.

But this isn’t why I keep revisiting Yunus, Daley-Harris and others who lead the organization. I do so because of the way they quietly change the world through tactics that run counter to the loud, insulting, name-calling manner in which many engage in today’s political discussions.

Why Americans shy away from causes

Daley-Harris outlined his theories behind transformational advocacy in his book “Reclaiming Our Democracy.” He writes that many Americans shy away from advocating for causes. “Why? Because most of us see advocacy as too hard or too frustrating, too complicated or too partisan, too dirty or too time-consuming, too ineffective or too costly.”

But there is nothing dirty or partisan about becoming friends with important lawmakers through frequent, unrelenting and kind interactions.

“The point is, there’s the silently groaning at home or there’s (holding) your protest sign, or there’s the building of a relationship.” That, he said, is the least known strategy, but it makes the most sense — and it works.

Trump Signs Substantial Foreign Aid Bill. Why? Maybe Kindness Was a Factor was originally published by Deseret News and is republished with permission.

Keep ReadingShow less

Recommended

man and woman walking on street during daytime

Photo by Sara Groblechner on Unsplash

Campus Civic Engagement: Democracy Innovation Prizes

Feb 24, 2026

When it comes to the crisis facing American democracy, many informed people ask a version of the question “What shall be done?”

The collective trauma hitting government norms, practices, and institutions elicits a fight or flight response (ask almost any therapist what they are seeing in their patients) - retreat and hide in fear, tremble in powerlessness, or act - resist, engage, and participate in all new ways.

Many Trump-aligned young people do the latter, with Turning Point USA being the most high-profile, but not the only, example. Others are turning to groups like Young Americans for Freedom, local Republican organizations, and elsewhere. Others attend protests for the first time in decades, become poll watchers, or speak up at school board meetings. Students on the left are marching, protesting, and speaking out in ways unseen in decades.

At the same time, colleges and universities are working to foster political engagement that doesn’t devolve into shouting matches (or worse). A lot of schools are finding ways to foster civic dialogue with bipartisan student groups or public events.

The School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University, on whose National Council I serve, has an endowed speaker series meant to foster vigorous and healthy debate. The university, like many, has a center for civic engagement that promotes voting and volunteering. All of this work at GW and around the country is important. But it isn’t enough. We need our students not just to be engaged citizens, but also democratic entrepreneurs.

To that end, I endowed a Democracy Innovation Prize in the School of Media and Public Affairs (SMPA) to promote creative solutions to the challenges facing our democracy. Modeled on business school plan or pitch competitions, the prize will reward students for finding ways to keep our 250-year-old experiment continually workable and meaningful in a complex society. The prize will recognize ideas and projects that are workable and meaningful. Every fall, SMPA will announce a problem that is big enough to matter and small enough to address, and ask students to solve it. For example, how to foster local media that audiences trust and support, how to build faith in public institutions that respond credibly and with impact, how to nurture a next generation of political candidates who bridge divides, or how to find new pathways for local, sustained civic impact beyond political parties and election cycles.

Finally, the Prize makes real the moment we are in. Democracy, its beliefs, and its institutions are not a given. Congress passed one piece of legislation last term. Faith in public institutions is down. The core values of voting and ballot integrity are a national question like never before. You would be hard-pressed to find someone who thinks American politics is healthy and thriving.

The enduring aspects of democracy are the citizens who inherit it and the beliefs shared by a majority. Concentrating hard now on what sustains, what can be fixed, and what can be put behind is the role of the students in these classrooms. The Prize aims to inspire them to bring these challenges to the forefront and make them practical.

This is only one of a few democracy-building programs at US universities - for now. These are investments that match hope with meaning. I fervently hope that others will follow my lead and start similar programs across the country. America is full of entrepreneurs and innovators. Those talents should not be limited to apps and tech; they should also be unleashed on our democracy.

John Barth endowed a new democracy innovation prize at the George Washington University.

Keep ReadingShow less

General view of Galileo Ferraris Ex Nuclear Power Plant on February 3, 2024 in Trino Vercellese, Italy. The former "Galileo Ferraris" thermoelectric power plant was built between 1991 and 1997 and opened in 1998.

Getty Images, Stefano Guidi

Powering the Future: Comparing U.S. Nuclear Energy Growth to French and Chinese Nuclear Successes

Feb 24, 2026

With the rise of artificial intelligence and a rapidly growing need for data centers, the U.S. is looking to exponentially increase its domestic energy production. One potential route is through nuclear energy—a form of clean energy that comes from splitting atoms (fission) or joining them together (fusion). Nuclear energy generates energy around the clock, making it one of the most reliable forms of clean energy. However, the U.S. has seen a decrease in nuclear energy production over the past 60 years; despite receiving 64 percent of Americans’ support in 2024, the development of nuclear energy projects has become increasingly expensive and time-consuming. Conversely, nuclear energy has achieved significant success in countries like France and China, who have heavily invested in the technology.

In the U.S., nuclear plants represent less than one percent of power stations. Despite only having 94 of them, American nuclear power plants produce nearly 20 percent of all the country’s electricity. Nuclear reactors generate enough electricity to power over 70 million homes a year, which is equivalent to about 18 percent of the electricity grid. Furthermore, its ability to withstand extreme weather conditions is vital to its longevity in the face of rising climate change-related weather events. However, certain concerns remain regarding the history of nuclear accidents, the multi-billion dollar cost of nuclear power plants, and how long they take to build.

U.S. Nuclear Energy Growth: A Comparison to France

Facing rising oil prices in the 1970s, France invested in nuclear energy to secure energy independence from other nations. A consolidated structure of policy and government actions allowed France to successfully invest and implement nuclear energy development. By relying on a domestic supply chain and simultaneously building multiple reactors of the same design, France became the lead exporter of energy in the EU, producing 70 percent of its clean energy through nuclear power. More recently, France has invested in nuclear power plants in the United Kingdom and Belgium, cementing their energy dominance across the EU.

The Energy Income Partners suggest the U.S. can learn from France to improve its nuclear energy capacity. Historically, France’s nuclear energy program was made by a single state-owned utility company: Electricité de France. By standardizing nuclear energy design and manufacturing, France lowered the cost of nuclear development. On the contrary, the U.S. spends significantly more and produces less efficiently because it splits its nuclear development into multiple companies with many different designs and manufacturers. Thus, the National Bureau of Economic Research recommended the U.S. deregulate and consolidate their operations—not only would this make production more efficient, but it would lead to greater carbon reductions than wind and solar combined.

U.S. Nuclear Energy Growth: A Comparison to China

The U.S. began building nuclear reactors in 1958, and still generates the highest percentage of nuclear power worldwide—yet it has drastically slowed its construction of power plants, building only three nuclear reactors in the past 13 years. Meanwhile, China built 13 in that same amount of time. Currently, China is building 27 nuclear reactors with average construction timelines of about seven years—far faster than any other country.

Additionally, unlike the U.S., the Chinese nuclear power industry has benefited from sustained state support. While the U.S. faces partisan politics and rotating leadership, Chinese president Xi Jinping and his party have been in office for over a decade and have emphasized nuclear energy growth. China has local strategies, strong centralized government policies, a booming domestic supply chain, and a skilled workforce allowing them to dominate modern nuclear energy development.

Unlike China, the West has seen a lull in nuclear power since the 1990s, driven by limited public support and escalating costs. The Roosevelt Institute found a strong correlation between rising materials and input content, and falling construction costs. China, unlike the U.S., has reduced much of its nuclear expenses by replacing foreign equipment with domestic products. The Roosevelt Institute therefore recommended that the U.S. streamline its regulatory frameworks and pursue domestic production of goods.

Recent Developments in U.S. Nuclear Policy

The U.S. has shut down eight reactors in the past decade, building only three new ones. The most recent nuclear power plants constructed were Plant Vogtle Unit 3 & 4 in 2023 and Watts Bar Unit 2 in 2016—the first constructed in over 30 years. Even then, Watts Bar Unit 2 began construction in 1973 but was suspended in 1985, and did not resume until 2007, highlighting U.S. inefficiency.

The 1979 partial reactor meltdown of Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear power plant—the worst nuclear accident in U.S. history—led to the development of the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, which implemented an intensive safety regulation program. Nevertheless, this incident, alongside the Chernobyl disaster seven years later, intensified public opposition to nuclear energy across the nation.

While this skepticism persisted for decades, support for nuclear energy began increasing steadily in 1996, gaining 72 percent of Americans’ support in 2025. Despite growing public approval, nuclear development faced challenges; frequent design changes and rework slowed nuclear development, while increased labor demands and reduced productivity exacerbated delays. Additionally, reliance on custom-built reactors drove material costs up, turning nuclear power plants into lengthy, expensive projects.

With widespread bipartisan support for nuclear energy in the United States, policy support for nuclear energy has begun to strengthen. Most recently, the Trump Administration endorsed it by claiming that “President Trump is providing a path forward for nuclear innovation.” At an energy and AI summit at Carnegie Mellon University, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick stated, “We need to embrace nuclear…because we have the power to do it—and if we don’t do it, we’re fools.”

To further this desire for investment in nuclear energy, the White House established the Reactor Pilot Program (EO 14301), with the goal of accelerating nuclear energy development by creating 10 nuclear reactor designs. The White House wants three new small-scale reactors running by summer of 2026 and a nuclear reactor on a U.S. military base. Strong bipartisan support at the federal level is essential to maintain momentum in building nuclear infrastructure.

Future Outlook

To increase nuclear production and match growing energy demands, advocates say, the U.S. can take valuable lessons from French and Chinese nuclear development strategies. Both nations have developed an extensive nuclear power sector through centralized planning, standardized designs, and strong domestic supply chains. Meanwhile, the U.S. has faced delays from high costs, complex regulations, and inconsistent approaches despite its technical expertise. To increase nuclear energy production, the U.S. could build a stronger domestic supply chain and standardize nuclear reactor designs. The rise of Artificial Intelligence and data centers is causing a massive demand for energy across the U.S., signaling increased need for diversified energy sources. It remains to be seen whether nuclear energy will rise to fill this gap.

Powering the Future: Comparing U.S. Nuclear Energy Growth to French and Chinese Nuclear Successes was originally published by The Alliance for Civic Engagement and is republished with permission.

Keep ReadingShow less

Should the U.S. nationalize elections? A constitutional analysis of federalism, the Elections Clause, and the risks of centralized control over voting systems.

Getty Images, SDI Productions

Why Nationalizing Elections Threatens America’s Federalist Design

Feb 23, 2026

The Federalism Question: Why Nationalizing Elections Deserves Skepticism

The renewed push to nationalize American elections, presented as a necessary reform to ensure uniformity and fairness, deserves the same skepticism our founders directed toward concentrated federal power. The proposal, though well-intentioned, misunderstands both the constitutional architecture of our republic and the practical wisdom in decentralized governance.

The Constitutional Framework Matters

The Constitution grants states explicit authority over the "Times, Places and Manner" of holding elections, with Congress retaining only the power to "make or alter such Regulations." This was not an oversight by the framers; it was intentional design. The Tenth Amendment reinforces this principle: powers not delegated to the federal government remain with the states and the people. Advocates for nationalization often cite the Elections Clause as justification, but constitutional permission is not constitutional wisdom.

Our federal system exists because the founders distrusted centralized power. They understood that dispersing authority creates checks against tyranny and incompetence. Managing elections at the state and local level creates 50 laboratories of democracy, each experimenting with methods that best serve their populations.

The Competence Problem

Consider the federal government's track record on large-scale administrative tasks. The healthcare.gov rollout, Veterans Affairs wait times, and Social Security Administration backlogs are not arguments against government itself, but they are reminders that bigger is not always better. Elections require logistical precision: maintaining voter rolls, training poll workers, securing thousands of voting locations, processing millions of ballots, and resolving disputes quickly.

Local election officials understand their communities. They know which neighborhoods need more polling places, which populations require language assistance, and how to navigate local geography and infrastructure. A federal bureaucracy in Washington cannot replicate this granular knowledge across 3,000 counties and 50 states.

The Diversity of Democracy

America's geographic, demographic, and cultural diversity is a feature, not a bug. What works in rural Montana may not work in urban Chicago. Alaska's vote-by-mail challenges differ from those in Florida. Nationalizing elections means imposing one-size-fits-all solutions on very different contexts.

Voter ID laws illustrate this tension. Some states find them essential for election integrity; others view them as unnecessary barriers. Early voting periods vary because communities have different needs and capacities. Ballot design and voting technology also benefit from local adaptation. Forcing uniformity eliminates the ability of communities to craft solutions for their unique circumstances.

The Security Argument Cuts Both Ways

Proponents argue that nationalization would enhance election security through standardization. But concentration creates vulnerability. Currently, a bad actor would need to compromise multiple independent systems across many jurisdictions to affect a national outcome. Nationalizing elections means creating a single point of failure: one system to hack, one bureaucracy to infiltrate, one set of procedures to exploit.

The 2020 election, whatever one's views on specific controversies, demonstrated the resilience of decentralization. Recounts and audits occurred in multiple states under different procedures and oversight. This redundancy provided verification mechanisms. A nationalized system would eliminate this protection.

Consider voting hours, ballot access rules, voter roll maintenance, vote-counting procedures, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Each involves choices that affect electoral outcomes. Trusting any single party with this authority is naive. The party out of power would cry foul, likely with justification, and public confidence in elections would deteriorate, not improve.

What Should We Do Instead?

None of this means the status quo is perfect. States should share best practices. Interstate cooperation on voter roll accuracy makes sense. Federal support for election security, particularly cybersecurity, is appropriate. Congress can and should protect fundamental voting rights against genuine state-level abuses.

But improvement doesn't require nationalization. We can strengthen elections while preserving the benefits of federalism. Support state election officials with resources and training. Facilitate information sharing without mandating uniformity. Protect voting rights through targeted intervention rather than wholesale federal takeover.

Conclusion

The impulse toward nationalization reflects frustration with legitimate problems: inconsistent practices, disputed results, and concerns about access and integrity. But frustration is not a governing philosophy. The remedy for federalism's difficulties is not to abandon it but to make it work better.

Our founders deliberately chose decentralization, and their wisdom endures. Elections conducted by states, under constitutional constraints and public scrutiny, remain our best protection against both incompetence and tyranny. We should think very carefully before trading this proven system for the uncertain promise of federal efficiency.

The question is not whether nationalizing elections could be done; technically, perhaps it could. The question is whether it should be done, and whether we are willing to accept the risks that would come with such a dramatic consolidation of power. Conservative caution suggests the answer is no.

Francis Johnson is a founding partner of Communications Resources LLC, a public affairs, public policy, public relations, and political consultancy specializing in government and media relations and corporate communications. He is the former President of Take Back Our Republic.

Keep ReadingShow less

Load More

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift