Chan is a research associate at RepresentWomen with a focus on ranked-choice voting.

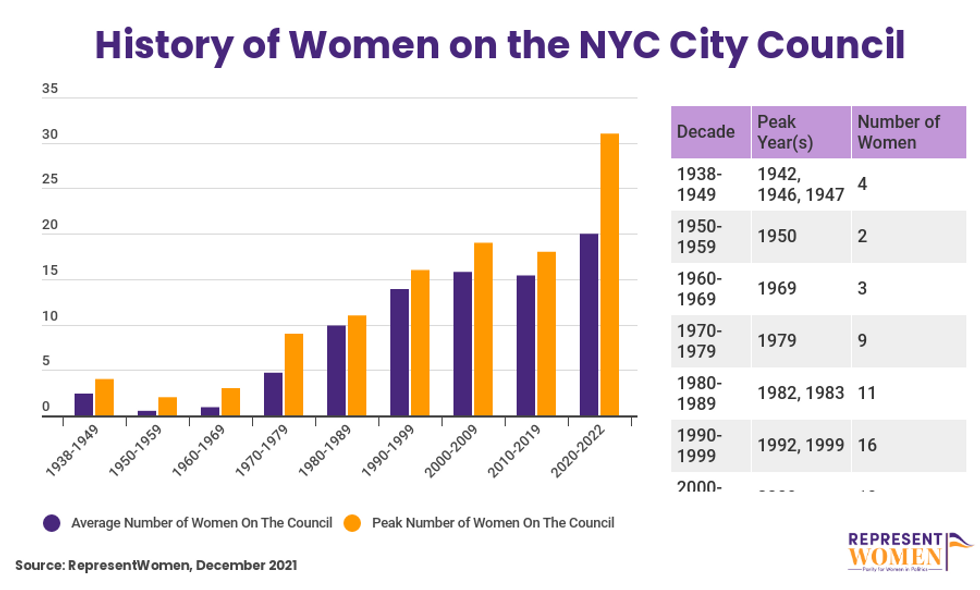

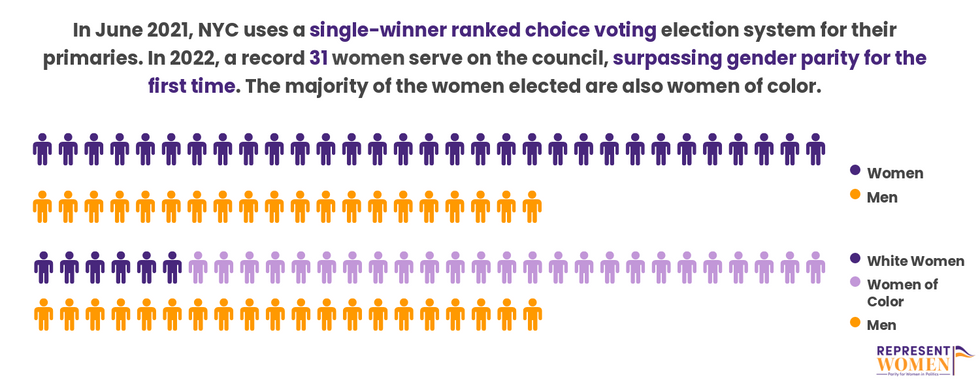

Last fall, New York elected a majority-women city council for the first time ever. This also happened to be the first time the city used ranked-choice voting and public financing. This is not a coincidence.

RepresentWomen’s research team is currently exploring the ins and outs of that election to uncover all the critical ingredients for such a historic outcome, and we’re looking forward to releasing a full report in June. As an appetizer, let's discuss the campaign finance aspects.

Women are underfunded

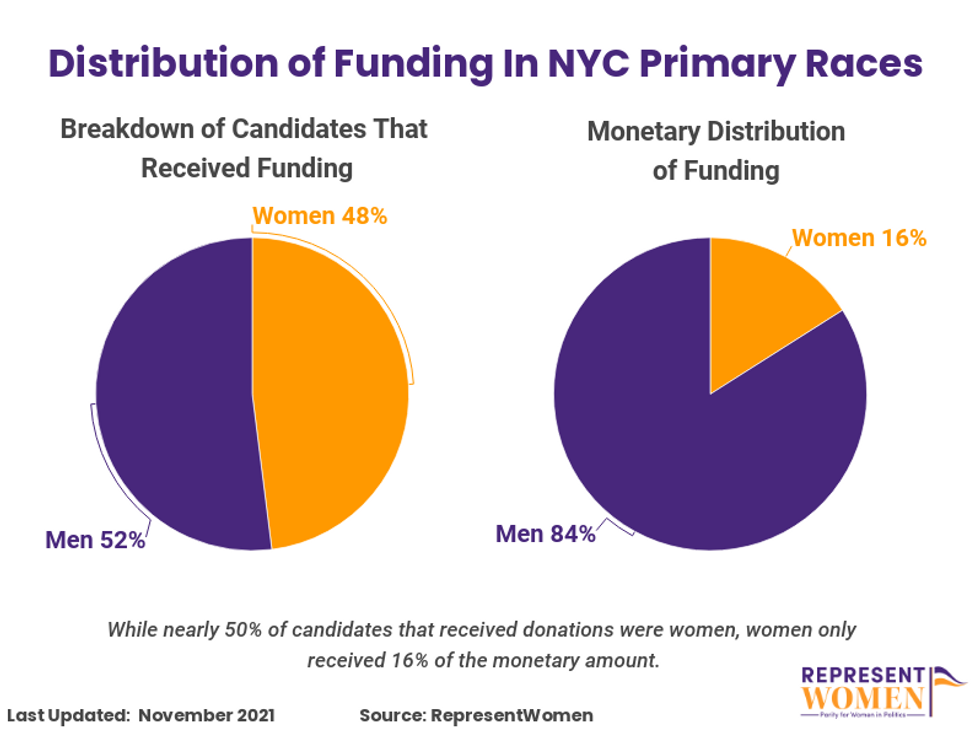

According to the Campaign Finance Board, half of candidates who were supported by independent spenders in the June 2021 primary were women, yet women received only 16 percent of the total dollars given by those donors.

Research also shows that individual donors and political action committees donate more frequently and give more money to male candidates than women, and, with these smaller donor networks, women struggle in crowded political fields.

A deeper dive into the spending data tells us that the mayoral race got much more donor attention than the other races: the total amount of funding in the mayoral race (excluding funds spent on attack ads) was more than 400 percent of the total funds in all the other races combined. Male candidates received 92.5 percent of the mayoral funds.

Despite the massive funding gap between male and female mayoral candidates, Kathryn Garcia still came within 1 percentage points of winning the mayoral race and women experienced historic wins to create an unprecedented female-majority on the city council.

How is it possible that so many women could win without nearly as many campaign donations?

Public financing was a key ingredient

The city's recently updated small-donor public matching funds program impacted the fundraising climate. The program included an increased matching rate of contributions, lowered contribution limits, and increased maximum matchable amounts for citywide offices. Since women rely more on small donors than men do, this boosted women’s access to campaign funds. Organizations on the ground in New York, like 21 in ‘21, also played a critical role in helping women candidates navigate the bureaucracy of the matching funds program.

In the city council races, both women and men had the same funding breakdown, with 74 percent of funds being from the public and the remainder coming from private sources. In the mayoral race, women candidates also mirrored that split, with around 75 percent of their funds coming from the public.

But men in the mayoral race relied more on private funds than public funds (a 57/4).

RCV + public financing: a perfect pairing

The city council primaries may have been quieter races, but they were just as significant as the mayoral election. For one, they provided ample evidence that, partnered with historic voter turnout, women are successful in ranked-choice elections. They also indicated that in a more equitable voting environment, such as an RCV election combined with public financing, private funding is not the only indicator of success. As research suggests, RCV levels the playing field for women who have thrown their hat into the male-dominated electoral ring. The results of this election support that research.

To achieve gender balance in our lifetimes, it’s clear that we need a twin-track approach that gives women the individual support they need while also breaking down the systemic barriers for women to run and win. New York offers an excellent example of structural reform’s power to achieve gender balance without having to wait another 400 years.

Now all eyes are on the New York city council to see the ways this historic diversity and representation improves policy processes and outcomes in the largest city in America. We believe they will rise above the task.