Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair of Political Science at Skidmore College and author of “A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law.”

This is the latest in “ A Republic, if we can keep it,” a series to assist American citizens on the bumpy road ahead this election year. By highlighting components, principles and stories of the Constitution, Breslin hopes to remind us that the American political experiment remains, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, the “most interesting in the world.”

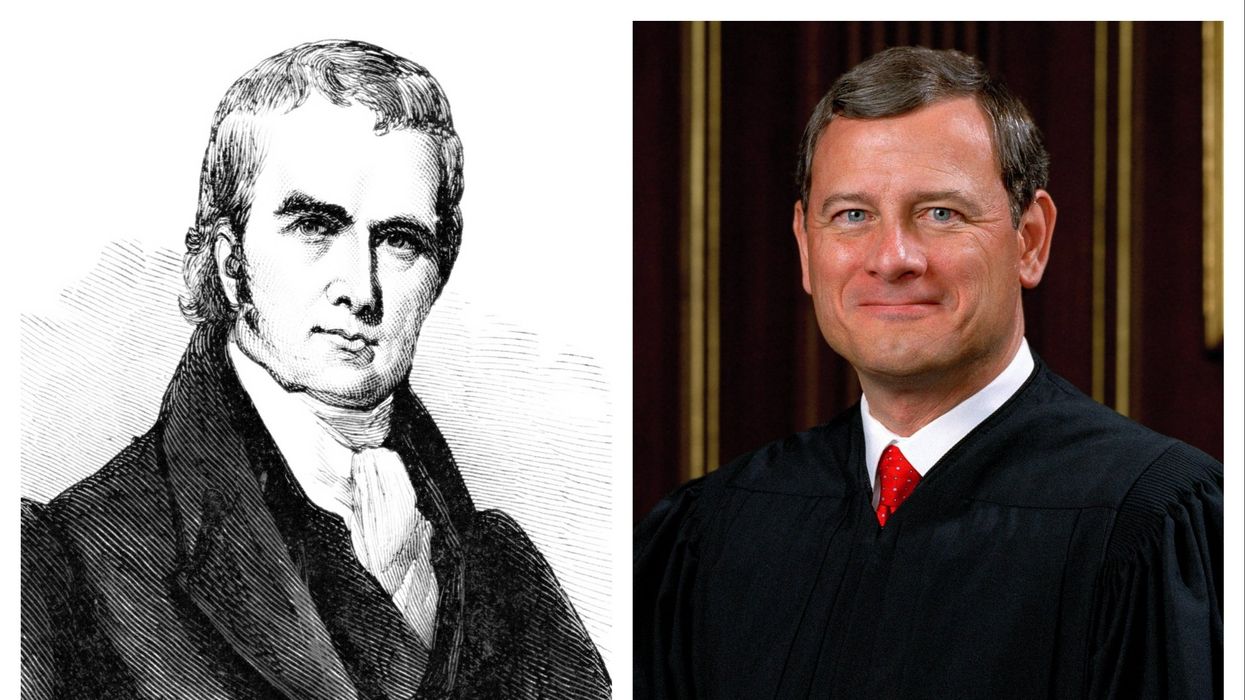

Chief Justices John Roberts and John Marshall share more in common than their ordinary forename and stressful day job. They both fiercely defended the reputation of America’s courts; they both presided over the nastiest political trials of their times; and they both couldn’t quite contain their disdain for some of the presidential antics that occurred under their watch.

And yet, tragically, it was their fundamental differences that were most on display with the court’s astonishing decision in Trump v. United States (2024). Roberts ran from a fight while Marshall, in Marbury v. Madison (1803), took one head on.

First, let’s set the stage. Both Roberts and Marshall led courts that were asked to define the breadth of presidential “immunity.” Both Roberts and Marshall were expected to issue their critical rulings during periods of enormous political anguish and discord. Both Roberts and Marshall gave legal victory to presidents who were seen by opponents as demagogic. Both Roberts and Marshall relied on procedural limitations to justify those victories. Both Roberts and Marshall will doubtless be remembered for the way in which they handled these two momentous cases.

Of course, all of those resemblances disguise the single crucial factor that differentiates the two jurists: Only one — Marshall — considered the greater good of the nation.

From an early age, most Americans are taught that John Marshall’s ruling in Marbury v. Madison changed the legal landscape because it formulated the courts’ power of judicial review. Few, however, recognize that it was also the first Supreme Court case to examine the scope of presidential prerogative, the close cousin to presidential immunity, presidential discretion and presidential privilege.

The facts are simple. After losing the presidential election to Thomas Jefferson and relinquishing majority control of Congress to the Jefferson-led Democratic-Republicans, incumbent John Adams sought to pack the one remaining governmental branch — the judiciary — with Federalist allies. He and the lame duck Congress thus passed a series of last-minute resolutions that permitted Adams to nominate Federalists to a few dozen newly created judicial openings. William Marbury was one of those “midnight appointments.” The problem arose when Adams ran out of time trying to deliver the commissions. Once in office, Jefferson instructed his secretary of state (John Marshall, interestingly) to bury Marbury’s contract. Marbury, without a commission or a job, threw up his hands and cried foul.

Jefferson’s defense for withholding Marbury’s commission was that he — Jefferson — was insulated from legal redress by some ambiguous conception of presidential discretion. He was immune. He could never be criminally or civilly liable for what he described as “political” acts, those that the Constitution may not enumerate, but that are part of the broad scope of Article II. The principle of presidential discretion, Jefferson insisted, was spacious enough to include keeping Marbury’s appointment in the proverbial drawer.

Marshall disagreed, and in an excoriating opinion told Jefferson so. Sure, Marshall admitted, a president has certain discretionary authority, “but when the legislature proceeds to impose on [him] other duties; when he is directed peremptorily to perform certain acts; when the rights of individuals are dependent on the performance of those acts; he is so far the officer of the law; is amenable to the laws for his conduct; and cannot at his discretion sport away the vested rights of others ” (emphasis added). Sorry, Mr. Jefferson, but no. Your argument about presidential discretion is unconvincing. “The United States is a government of laws,” the great chief justice admonished, “not of men.”

Marshall scolded Jefferson for abridging Marbury’s rights. He humiliated the president for declaring that he was above the law. He denounced the Virginian for putting personal motivations above national interests. He essentially called Jefferson a bully. And then he allowed Jefferson to win. Indeed, Marshall’s brilliant ruling stuck precisely because the president emerged victorious. Jefferson could keep the commissions, but the judiciary would hold on to the power of judicial review. A profitable exchange for the courts, to be sure.

In contrast, the current chief justice cowered at the feet of America’s biggest bully. The conservative majority in Trump v. United States, led by Roberts, seemingly rejected all the lessons handed down by Marshall. They granted presidents immunity for all “official” executive actions, and in the process sanctioned potential violations of the law. They provided a shield for presidents to “sport away the vested rights of others.” As long as the president acts in their official capacity, the ruling concludes, rights, privileges and, yes, metaphorical commissions can be withheld. What is most heartbreaking about the outcome of Trump v. United States is that the court received nothing in exchange, except perhaps a further tarnished legacy.

Chief Justice Roberts’ haughty dismissal of Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s opinion says it all. “Fear mongering on the basis of extreme hypotheticals about a future where the President ‘feels empowered to violate federal criminal law,” he called the very real apprehension expressed by the three dissenting justices. Fear mongering. What all Americans should fear is a Supreme Court that repeatedly, and cavalierly, relinquishes power to an imperial president.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift