Frazier will join the law school faculty at the University of South Dakota as a Visiting Professor starting Academic Year 2023.

The “American Experiment” ended at some point. Our collective willingness to test new forms of governance dried up. Perhaps the nation grew complacent. Whatever the cause, the United States no longer appears to be a place where “the people” look for novel and substantial ways to ensure their government effectuates their will. Our overreliance on elections as the means and ends of our democratic engagement and oversight demonstrates the lack of democratic innovation and ingenuity among we, the people. It’s time to acknowledge that our flawed, but functioning system may need some updates beyond improving access to the ballot.

In theory, elections provide accountability by allowing for the replacement of officials who fail to advance the will of the people. In actuality, incumbents usually breeze through elections -- regardless of their fidelity to the will and needs of their constituents. In the 2022 midterms, 94% of incumbent state and local officials won reelection. If elections served as a true means of accountability, then retention rates should drop, especially in light of persistent inflation, continued economic inequality, and a slew of other policy failures.

Elections lend legitimacy to elected officials and the government by conveying the consent of the people to those officials exercising the people’s sovereign power, right? Again, wrong. Unless “the people” are ok with an unrepresentative group offering their consent, then elections fall short in this regard as well. Consider that an "usually high turnout" took place in the 2018 midterms -- when 47.5% of the voting age population actually turned out to vote. In the recent 2022 midterms, voters fell short of the “high” turnout rate from 2018 -- preliminary results suggest that just 46.8% of voters attempted to provide their consent via the ballot last November. In any other context, such a small percentage of the collective making such big decisions on behalf of everyone would be called out as ludicrous. Surely a classroom of 20 kindergartners would raise hell if 9 of them dictated whether they would have recess that day. It’s far from childish for voters to protest this arrangement.

The unrepresentativeness of the few eligible voters who actually participate in elections further diminishes the idea that elections convey the consent of the people. Voters tend to be older - whereas 72% of eligible voters over the age of 65 voted in the November 2020 election, just 49% of voters under the age of 25 did the same. Voters also tend to be whiter. Approximately 65% of White eligible voters turned out in the November 2016 election. Comparatively non-white voters turned out at much lower rates: 59.6% among Black voters; 49.3% among Asian voters; and, 47.6% among Hispanic voters. “The people” have cause to wonder whether such an unrepresentative and small sample of Americans can consent to whichever government results from an election.

The low turnout rate also indicates that elections ought not to be regarded as the people’s sole or even primary way of democratic participation. The narrative spun by political parties -- that voting is the most important form of democratic expression -- is self-serving and inaccurate. Parties try so hard to turnout voters because their power hinges on the people perceiving elections as a means of accountability and as an expression of their consent.

Democratic participation was meant to go beyond rubber-stamping incumbents to serve another term. For example, the Founding Fathers developed the jury system to give the people a role in the justice system and to prevent the enforcement of unjust laws via nullification. The vast majority of Americans agree that serving on a jury is a part of what it means to be a good citizen; yet, this form of participation has disappeared faster than a kid's snow cone during a Fourth of July parade - in 2016, just 43,697 people across the nation actually served on a federal petit jury, a decrease from the 71,578 who served in 2006.

Finally, it is not clear that we, the people, actually have the largest effect on election outcomes. As reported by the New York Times, wildly inaccurate and partisan polls likely skew campaign donations and alter voters’ decision to head to the polls or stay home. Money also shapes who voters can elect, if they even decide to turnout. Capacity to raise funds, rather than capacity to advocate for voters, decides who can run for office. And, similarly, the capacity to out-fundraise opponents is likely the deciding factor in whether a candidate can win their primary election.

Political parties are aware of the limited value of a vote when compared to the value of a dollar. Donations appear more valuable than votes to the parties -- as pointed out by Katherine Gehl, Democrats cannot send an extra Blue vote from San Francisco to El Paso, but they can transfer funds from a California donor to a candidate in Texas. Despite the fact that the current system results in partisan elected officials spending half their time dialing for dollars, the people still persist in thinking that elections offer the best means of accountability, legitimacy, and representativeness.

While it’s true that election fraud is - for lack of a better phrase - not a thing, it is fraud to perpetuate the idea we cannot do better than elections when it comes to empowering we, the people, to delegate our sovereign authority.

Citizen assemblies, made up of randomly selected individuals and granted some degree of legislative authority, can and should serve as a complement to and, perhaps eventually, substitute for our current election-centric approach to democracy. Imagine, for example, a state randomly selecting 100 residents to take the place of or supplement the work of their state legislature. These residents would mirror the demographics of the state -- they would bring diverse backgrounds, experiences, and ideologies to the assembly.

Assemblies can provide the people with a more responsive and unbiased policymaking body that could advance their will by vetoing bills, setting the legislative agenda, or determining whether a bill should be referred to the people via a ballot initiative. There’s no shortage of variations in terms of the size and authority of such an assembly. In fact, the creation of such assemblies should include opportunities to make adjustments to better realize their democratic potential.

The bottom line is that selecting our policymakers through elections has become profoundly undemocratic. Elections appear to no longer serve as accountability mechanisms; they increasingly fail to provide a sense of legitimacy; and, they often result in the election of hyper-partisan, unrepresentative officials.

Surely, we can use our democratic imagination to develop new processes to complement elections that better allow the people to participate in and control their democracy. Citizen assemblies are one such process, but others are out there. These processes are not perfect and will take time to refine, but learning and evolving are inherent to all experiments -- including democratic experiments. We know what elections produce…and those dismal results should encourage us all to innovate and not just around the edges.

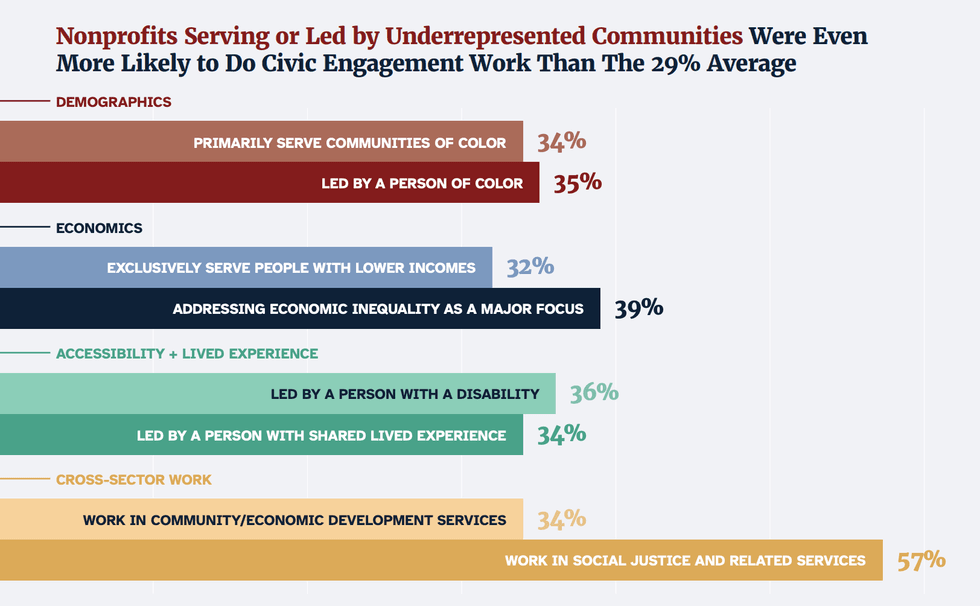

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift