Schalit is senior editor of politcs and society for The Conversation US.

President Joe Biden chose Atlanta – the historic home of the 20th century’s battle for civil and voting rights – to make a strong argument on Jan. 11, 2021, that the Senate must ditch the filibuster and pass legislation soon to protect voting rights.

Biden told his audience, “I will defend your right to vote and our democracy against all enemies foreign and domestic.”

After Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential election, Trump’s false assertions of election fraud sparked Republican-dominated state legislatures to pass bills that Democrats say restrict voting rights and place election administration in the hands of rank partisans. GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell says those charges are just “ scary stories … about how democracy is at death’s door.”

As part of our focus on how democracy works, The Conversation asked scholars to look at various aspects of voting rights. Here is a selection of their stories to provide more background to today’s consequential conflict. The strong message from all of these: The outrage generated by these laws may be out of proportion to their true impact.

1. Easy voting does not equal voter fraud

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of changes before the 2020 election that made voting more convenient. Some states adopted or expanded mail-in voting and liberalized absentee voting rules. Others introduced or expanded the use of drop boxes in which voters could place ballots. Early voting periods were extended.

But since the election, the GOP’s false claims of voter fraud “are being repeated as justification for proposals to claw back recent advances that have made voting easier for Americans,” writes political scientist Douglas R. Hess.

The 2020 election was the ultimate stress test for the country’s election system. Yet the federal government’s election security agencies called it the “most secure in American history.”

That means, writes Hess, that “the often-claimed trade-off between election integrity and reasonable measures to make it easier for people to vote is, in fact, largely false.”

Read more: Making it easier to vote does not threaten election integrity

2. Claims of voter suppression don’t hold up

Election law scholar Derek Muller takes issue with the negative characterization of the many recent election law changes. He examined the statutes that politicians and advocates have called “voting restrictions.”

While some, Muller writes, “could fairly be given that label, many are ordinary rules of election administration that simply don’t merit those labels. Many bills will likely have no discernible effect, much less a negative effect, on the right to vote.”

One example, says Muller: A Utah bill “updates a law about how to remove dead people from the list of registered voters” and was passed unanimously by both houses of the Utah legislature. Among other straightforward elements of the bill is a provision that “increases the communication surrounding death certificates to election officials.” But that bill, Muller writes, was described by one voter advocacy group as restricting the right to vote.

Read more: Claims of voter suppression in newly enacted state laws don't all hold up under closer review

3. Some voter suppression efforts won’t change election results

Georgia, where Biden chose to make his speech on voting rights, has been a special focus for GOP-led efforts to limit those rights.

Georgia’s new voting laws “ don’t really affect who is eligible to vote,” writes political scientist Bernard Tamas, “but they do make voting more difficult for poorer populations and those living in urban areas.”

Yet these laws may not change election results much, “if at all,” Tamas writes. That’s because most U.S. voting districts – for both Congress and state legislatures – are “safely controlled by one party or the other. Laws that slightly reduce the number of potential voters are unlikely to shift power in Congress and state legislatures significantly.”

Read more: Georgia voter suppression efforts may not change election results much

4. A surprising ending to 2020 absentee ballot conflicts

Pitched legal battles were waged in the run-up to the 2020 election over extending the regular deadlines – usually election night – for returning absentee ballots. There were two related reasons. First, the pandemic meant a huge surge in absentee ballots. Second, some expressed legitimate concerns about the capacity and integrity of the U.S. Postal Service to handle the volume of ballots in a timely way. In general, Democrats wanted deadlines extended; Republicans fought those extensions.

Constitutional law scholar Richard Pildes writes about the legal fight over ballot deadlines in Wisconsin and Minnesota. “In both, voters might be predicted to be the most confused about the deadline for returning absentee ballots, because those deadlines kept changing,” he writes.

A federal district court ordered Wisconsin to extend its election night absentee deadline by six days; the Supreme Court blocked that order and restored the state’s deadline. That led Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan to lament in her dissent that tens of thousands of voters would lose their right to vote by missing that deadline. A similar legal conflict played out in Minnesota.

Yet in the end, Pildes writes, post-election audits showed that “even though voting-rights plaintiffs lost their battles close to Election Day in both Wisconsin and Minnesota, with the deadlines shifting back and forth, only a tiny number of ballots arrived too late.”

Read more: There's a surprising ending to all the 2020 election conflicts over absentee ballot deadlines

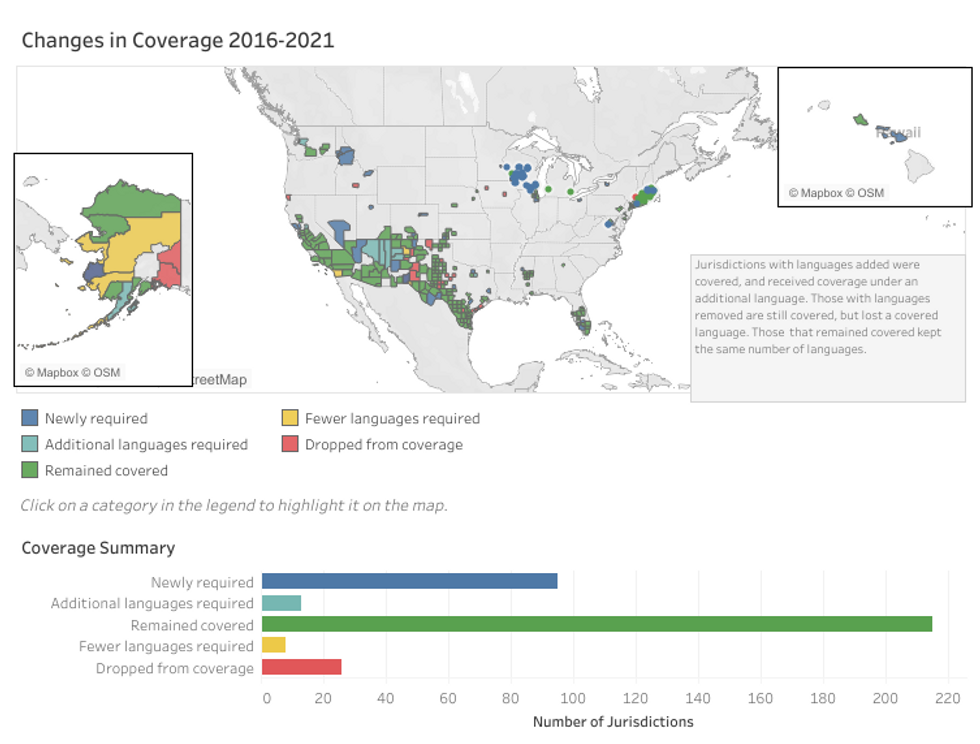

5. More Americans can vote in their native languages

It’s hard to vote when you don’t understand English. Communities with high numbers of citizens with limited proficiency in English have lower voter turnout. So the federal Voting Rights Act, write researchers Gabe Osterhout and Lantz McGinnis-Brown at the Idaho Policy Institute at Boise State University, requires those communities with significant groups of voters who are not proficient in English “ to provide election materials in that group’s language.”

Those materials range from registration and voting notices to actual ballots.

In December 2021, the list of places that would have to supply such materials was issued, and it includes “331 jurisdictions in 30 states” that are “are home to 80.2 million voting-age citizens, including 20 million people of Hispanic backgrounds.”

The effect of all this information, Osterhout and McGinnis-Brown write, is increased voter turnout among citizens who speak languages other than English.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Click here to read the original article.

![]()

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift