Goldstone, a freelance writer, is the author of "On Account of Race: The Supreme Court, White Supremacy, and the Ravaging of African American Voting Rights."

This is the first in a three-part series on election integrity. The second part will look ahead to the 2024 election and the third will discuss why all Americans should oppose efforts to politicize vote-counting.

Until recently, asserting that the 2024 presidential election would mark the end of American democracy would have seemed hyperbole, even ludicrous. No longer. Observers as diverse as Bill Maher and the Cato Institute's Andy Craig have warned that a "slow-moving coup" or the "end of peaceful transfer of power in America" has already been put in motion by Donald Trump and his enablers in the Republican Party.

Their case is persuasive. Trump Republicans have been purging the party of apostates on the national, state and local levels, as well as enacting state laws that would allow party operatives to overrule nonpartisan election officials and substitute election results more to their liking. According to Craig, "Fringe legal theories about how to subvert the election are being workshopped and moved into the mainstream of Republican thought even as we speak. If Trump runs again, a near certainty, and the 2024 election result is close, the country could face a constitutional crisis with a potential for political violence that would make 2020 look tame."

That subversion of a free and fair election is even possible is due to deep flaws in the Constitution, which does not include specific rules as to how presidential elections will be conducted and certified. Most Americans are both unaware of these shortcomings and blissfully ignorant of the potential for a would-be autocrat to suborn the electoral process and seize power. In addition, most of those who believe a fraudulent presidential election would not be possible are unaware that one has already occurred.

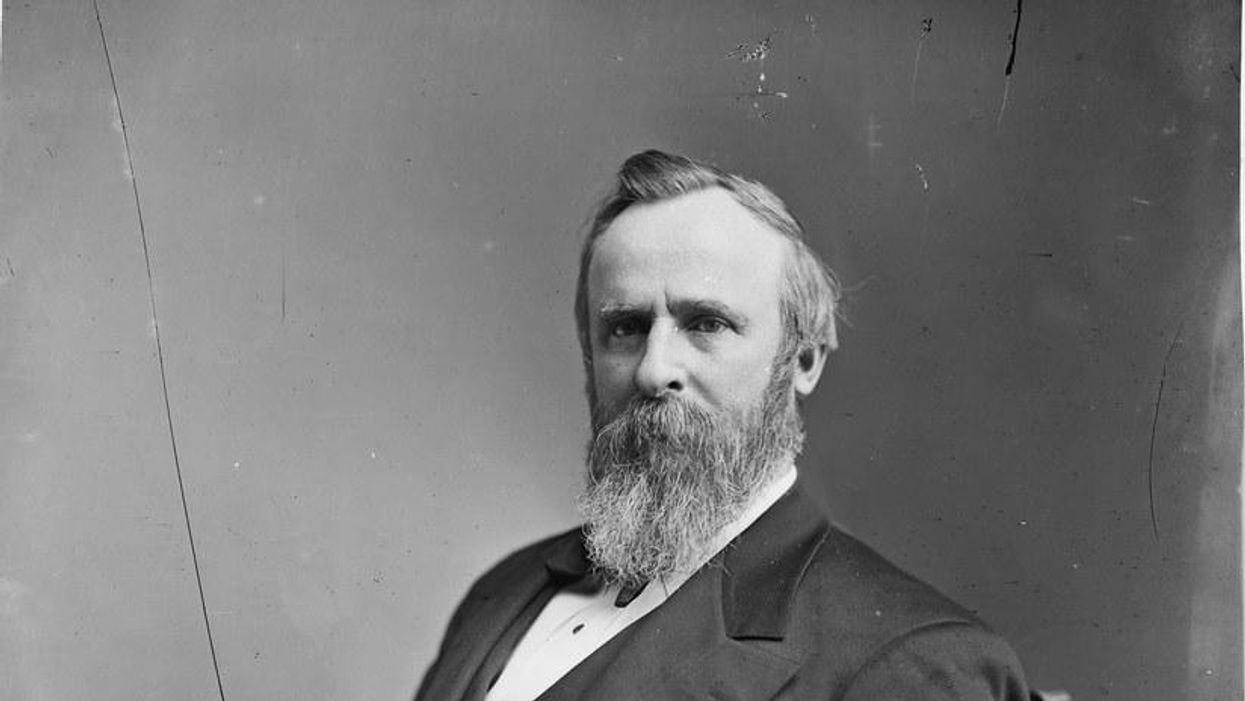

In 1876, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes ran against Democrat Samuel Tilden. The Republicans, the party of Lincoln, had been champions of equal rights for newly freed slaves and had even initiated an army of occupation in the defeated Confederacy to ensure them. Democrats, at least in the South, were the party of white supremacy.

But the nation had grown weary of Reconstruction and Tilden won the popular vote handily. He could also clearly claim 184 electoral votes, one short of the number needed for election. Hayes could claim only 165. Twenty electoral votes were in dispute, nineteen of which were in the three Reconstruction states still titularly under Republican control: Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina. In each of those, election officials declared Tilden the winner, but accounts of fraud and voter intimidation against African Americans were widespread. (The Army could not be everywhere.) Nonetheless, given an absence of proof, Tilden seemed to deserve the presidency.

Virtually every newspaper in America reported a Tilden victory, but not The New York Times, whose managing editor, John C. Reid, had been a prisoner of war at the infamous Andersonville stockade during the Civil War. Reid loathed Democrats and convinced Republican leaders to contest the result. New York Republicans wired partisans in the disputed states to hold out. Two days later, the Times ran the Page 1 headline "The Battle Won. Governor Hayes Elected." The article, which awarded Louisiana, Florida and South Carolina to Hayes, claimed to base its contention on in-state canvasses, although the Times was vague on just who had done the canvassing.

Only after the Times ran its piece did Republicans in the three states appoint canvassing boards, which not surprisingly ignored the reported vote totals, confirmed the Times assertion and declared Hayes the winner.

Democrats howled fraud. Threats of armed insurrection spread throughout Washington. Calls for secession were heard for the first time since the war. A shot was fired at Hayes' home in Ohio while the candidate was having dinner inside.

No constitutional provision existed to handle this crisis, but the necessity to devise some solution was apparent to both sides. Eventually, the decision was reached to appoint a 15-man Electoral Commission: five senators; five representatives; and five Supreme Court justices. Fourteen would be members of the two parties, divided equally, and the fifteenth nonpartisan. Little knowledge of politics and even less of arithmetic is necessary to recognize that, in effect, one man, hopefully worthy of Diogenes, would choose the president.

Incredibly, such a man seemed to both exist and be available. Associate Supreme Court Justice David Davis, a Lincoln appointee, was deemed acceptable to both sides. In what was certain to be an 8-7 vote, he would be the ideal eighth. So trusted as an independent was the justice that it was said, "No one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred."

But before the commission could meet, the Democratic-controlled legislature in Illinois offered Davis a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate, hoping Davis would decline but be grateful to Democrats for the gesture. Republican newspapers denounced the scheme, but Davis flummoxed the Democrats by resigning from the bench to accept the appointment.

With Davis now ineligible, one of the remaining four justices would be forced to sit in his place. Each was associated with one of the political parties. Eventually, for reasons never made public, Associate Justice Joseph Philo Bradley, recently appointed by Republican Ulysses S. Grant was chosen to take Davis' place. Democrats claimed a fix, but after the Davis fiasco their credibility was strained. Bradley accepted the appointment and thus became the only man in American history empowered to choose a president on his own.

Before deciding which man would be declared the winner, Bradley meticulously drew up a written opinion for each man, and then, after all this supposed soul-searching, surprised no one and chose Hayes. Democrats once more threatened rebellion. Rumors circulated that an army of 100,000 men was prepared to march on the capital to prevent "Rutherfraud" or "His Fraudulency" from being sworn in. In the House of Representatives, Democrats began a filibuster to prevent Hayes' inauguration.

What happened next has been a subject of debate among scholars ever since. Historian Alan Peskin wrote, "Reasonable men in both parties struck a bargain at Wormley's Hotel. There, in the traditional smoke-filled room, emissaries of Hayes agreed to abandon the Republican state governments in Louisiana and South Carolina while southern Democrats agreed to abandon the filibuster and thus trade off the presidency in exchange for the end of Reconstruction." The "Compromise of 1877," as it came to be known, made Hayes the 19th president of the United States. As one of his first orders of business, this supposed defender of African American rights ordered federal troops withdrawn from the South. When the soldiers marched out, they took Reconstruction and equal rights with them.

The 1876 election had all the elements that will potentially be present in 2024: a nation cleaved in two; a resurgence of white supremacy; accusations of voter fraud; corrupt election officials; an influential media outlet seeking to overturn the result; even the distinct possibility of armed conflict. But that election had something the 2024 contest will not — a convenient scapegoat that allowed both sides to overcome their mutual loathing and come together in compromise: African Americans. Democrats were so determined to end the military occupation in the South and thereby have an open field to restore white minority rule and return Black Americans to slavery in all but name that they were willing to sacrifice the presidency to do it.

The perpetuation of free elections, the cornerstone of democracy, transcends — or should transcend — partisan politics. All Americans, be they Democrats, Republicans or independents, can and should commit themselves to thwarting any effort, no matter from where on the ideological spectrum it emanates, to destroy that which untold thousands of their fellow citizens fought and died for. Democracy is precious but cannot be preserved through apathy. The nation needs desperately for people of good faith, regardless of political affiliation, to join together so that our form of government can be passed on to generations to come.