Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

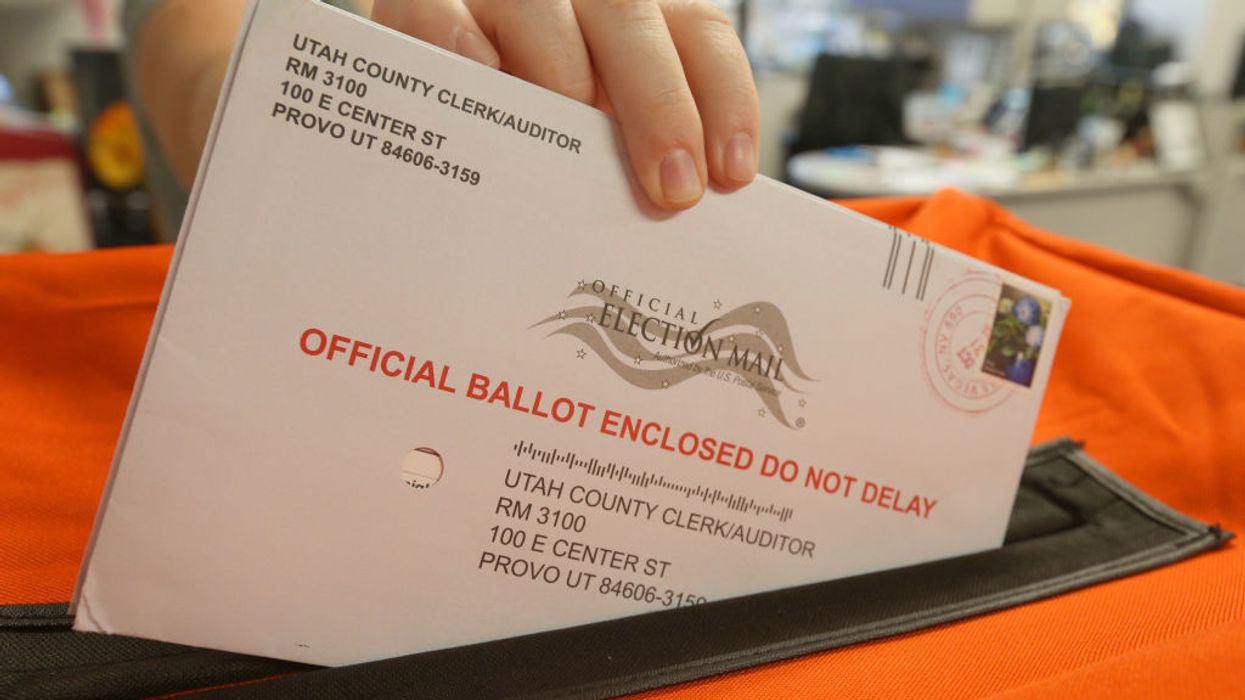

It is an article of faith among those who do not believe Donald Trump lost in 2020 that mailing ballots to voters increases illegal voting — often called voter fraud.

“Before the machines were introduced, vote riggers needed a way to cheat and it always involved generating LOOSE BALLOTS,” read a recent post on a pro-Trump Telegram “ election education ” channel. “It’s possible and therefore it happens,” said a nearby post.

It is understandable why disappointed Trump supporters are wary of mailed-out ballots. The Covid-19 pandemic led to a historic expansion of their use as a way to protect voters and election workers. By the time the 2020 election ended, 73 million Americans — 46 percent of all voters nationwide — had voted with a mailed-out ballot. That volume was nearly triple the voters who received a ballot by mail in 2018’s general election.

But articles of faith are not facts. As the 2024 presidential cycle revs up and Trump, the likely GOP nominee, keeps attacking elections, it is worth revisiting the most extensive national study by political scientists that looked at whether mailed-out ballots have any relation to voter fraud. In a word, their answer was “no.” That conclusion was based on comparing incidents of illegal voting during the two decades before the 2020 presidential election to the increasing use of mailed-out ballots during that time.

“If voting by mail creates more opportunities for fraud, those opportunities do not appear to have been realized in the data,” George Mason University assistant professor Jonathan Auerbach and Stephen Pierson, director of science policy for the American Statistical Association, wrote in their 2021 analysis for ASA’s journal, Statistics and Public Policy.

The statisticians are not saying voter fraud does not exist. They are showing — with state-by-state data from 2000 through 2019 — that it is exceptionally rare. When illegal voting has occurred, their charts reveal, it usually involves no more than several dozen ballots. That volume is nowhere near the thousands of votes that would have been needed to alter the closest recent presidential election margins.

It is important to emphasize how rare illegal voting is — despite partisan rhetoric. In my book, “ Democracy Betrayed,” which looks at anti-democratic efforts by both major parties in the 2016 election, I noted the extent to which some Republicans have overclaimed about illegal voting for years. That effort has been led by the right-wing Heritage Foundation, which has compiled and hyped a database of illegal voting across America.

As of 2016, when Trump was elected president, Heritage’s dataset cited 492 cases and 733 convictions between 1984 and 2016. That is one case for every 2 million presidential voters (approximately 980 million presidential votes were cast). If you count by convictions, with some people pleading to more than one charge, that total is still less than one in a million voters. In other words, illegal voting is not rampant.

Nonetheless, the statisticians used Heritage’s database and another dataset compiled by Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism. The researchers probed to see if illegal voting was more prevalent in the states that mailed ballots to voters by comparing the rates of voter fraud in states that did — and did not — mail ballots. They also looked to see if instances of voter fraud grew after a state began mailing ballots to voters. They found no relation between mailing ballots and illegal voting.

What the researchers did find, however, was that illegal voting was most prevalent in local races, where a small number of votes could alter the outcome. In other words, in the few instances where illegal voting happened, it was not in a presidential election — the contest that has been the focus of the attacks on mail voting by Trump’s base.

“A large amount of fraud comes from primaries and state and local elections,” they wrote. “These elections typically have lower turnout, and local elections may exist only in select parts of the state.”

Again, the researchers are not saying that voter fraud is non-existent. But they are saying that after examining 20 years of state-by-state data, “we find no evidence to suggest that voting by mail increases the risk of voter fraud overall. We believe our findings are unlikely were fraud much more common when elections are held by mail.”

That conclusion is worth remembering as accusations surrounding mailed-out ballots continue in 2024. Of course, there are other academic studies that assess the impact that mailing ballots has on voter turnout. States that mail ballots have some of the highest voter participation rates, which factually benefits both parties. However, 2020 presidential election deniers don’t believe that assessment either.