All across the country, the consistent theme of this presidential year has been turmoil.

A confusingly huge field of candidates vying to take on a norm-busting incumbent was just the start. The normally boring rules for conducting elections have been in high-profile upheaval since the coronavirus outbreak took hold in the spring, as most states grappled with how to steer voting away from polling places and got whipsawed between claims of voter suppression by Democrats and allegations of voter fraud by Republicans.

But in the eye of the tempest has been this rare note of agreement: When it comes to running a fair, efficient and calm election that's reliant on mail ballots, the place to look for guidance is Colorado.

Its politics remain just purple enough to assure plenty of bare-knuckle battling for the slightest electoral advantage. But the centerpiece of the Rocky Mountain region has still emerged as a national model — during the pandemic and beyond — for states looking to mostly remote elections as a way to produce routinely high turnout and consistently low levels of dispute after even the closest contests.

Two weeks before Election Day, the state's system has been operating nearly flawlessly so far, the fourth time it's been deployed for a federal election. More than 4 million voting packets started arriving in Colorado mailboxes two weekends ago, and on Monday tabulating got started on the record-smashing 638,000 ballots returned so far — almost a quarter of the statewide total four years ago. Nearly complete returns are highly likely to be reported quickly the night of Nov. 3, after the polls close for the 6 percent of the state that still votes in person.

Colorado was not the first state to switch to almost all vote-by-mail elections (that was Oregon, in 2000) and it was not the most populous to do so before this year's pandemic (that's Washington). But the state's top election's official, Secretary of State Jena Griswold, does not shy away from boasting that her system is best.

"Colorado is the gold standard for the nation," Griswold, a Democrat, said during a virtual election seminar last month. The same phrase has been used at least nine times this year in news releases and on her agency's website.

But it was not always this way, in anybody's eyes. And how it reached its current elite status is a tale of careful legislating and rulemaking; the building of bipartisan trust and pride of ownership among local election officials and the public; and continuous improvement in the mechanics of elections in response to the needs of voters.

Reaction to troubled history

Fifteen years ago, the headlines about Colorado elections focused on all the allegations of fraud the previous fall, when the top of the ballot featured intensely contested races for president (President George W. Bush narrowly turned the state red) and senator (Ken Salazar just as narrowly secured an open seat for the Democrats.)

Hundreds were being investigated for violations ranging from casting multiple ballots in 2004 to forging signatures and voting when ineligible. Prosecutors in three-fourths of the state's counties conducted probes and a dozen reported problems.

As late as 2012, Colorado found itself receiving the ignominious honor of being cited in a report by several prominent watchdog groups as among the six states least prepared to catch and correct voting system problems.

The following May, after Democrats ended a run of divided government by taking total control of the statehouse as well as the governor's mansion, saw enactment of the measure that's been the game-changer for Colorado elections.

The law, which every Republican in the General Assembly opposed, means all registered voters automatically receive a ballot in the mail before every primary and general election. It got rid of assigned neighborhood polling places in favor of voter service centers, open to anyone in a county who wanted to cast a ballot in person, drop off a completed ballot — or register and then vote as late as Election Day.

One reason the electorate was ready for the changes was that 7 of every 10 voters had already opted to automatically receive an absentee ballot for every election, and the same share of votes were routinely being cast that way.

Moreover, the changes were written with the help of local election officials and so had buy-in from those people, who live daily with the details of what can be a tremendously complex process.

"What happens across the country is legislation gets drafted without the experts who run elections involved," said Amber McReynolds, who ran elections in Denver at the time and is now CEO of the nonpartisan National Vote at Home Institute. "We did that differently in Colorado."

Last month provided one high-profile example of what can go wrong when even well-intentioned efforts to smooth the voting process get started without consulting election officials.

The Postal Service printed, and started sending to addresses nationwide, a postcard officials described as a good-faith effort to encourage people deciding to vote by mail to do so early — so as not to have their ballots disqualified because of missed deadlines. But the mailers caused plenty of confusion when they started arriving in Colorado, and other states where ballots are sent out proactively, because they talked about application procedures and other rules that don't apply.

Griswald quickly sued, at first getting a judge to halt the flow of postcards into her state and later reaching a settlement under which USPS promised to get a sign-off from Colorado officials on any other outreach connected to mail-in voting.

Higher turnout, lower costs

Among the measurable impacts of the switch to almost all vote-by-mail elections has been an increase in turnout and a decrease in cost.

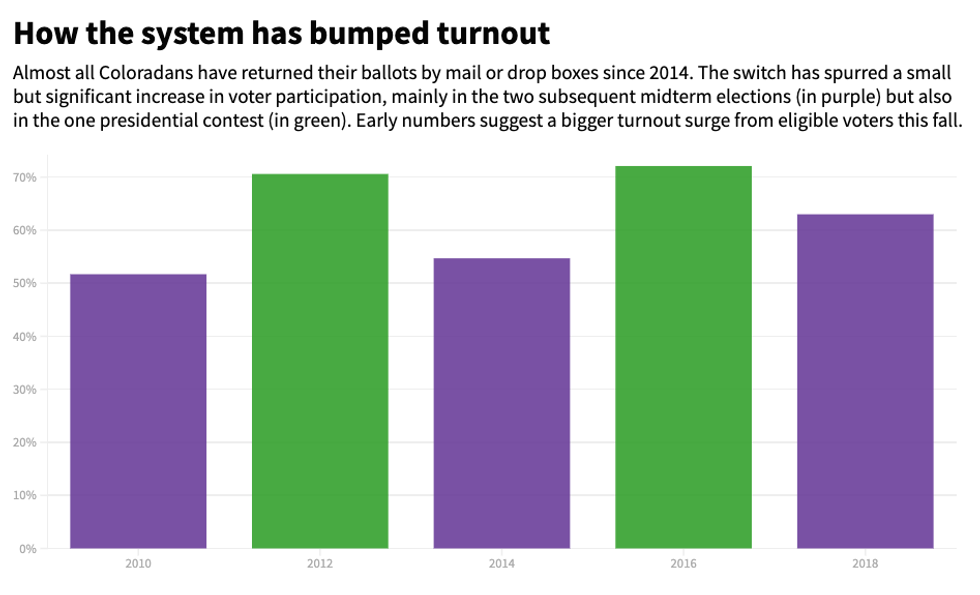

Voter participation in Colorado was better than average even before the change. In 2010, the last midterm election under the old system, turnout was 51 percent of those eligible, 6 percentage points above the national average and eighth best among the 50 states.

Source: United States Election Project

Source: United States Election Project

But four years later, in the first mostly mail-in general election, and helped by a highly competitive Senate contest, turnout grew to 54 percent and No. 4 nationally — 12 points better than the national number, which sank to its lowest level since World War II.

The turnout has continued growing. It was 61 percent even without a Senate race in the November 2018 midterm. And it was 43 percent for this year's primaries, second-highest in the nation. (Three of the other states that planned for mostly by-mail elections this year before the Covid-19 outbreak — Oregon, Washington and Hawaii — were in the top six for primary turnout. The other, Utah, inexplicable lagged behind.) .

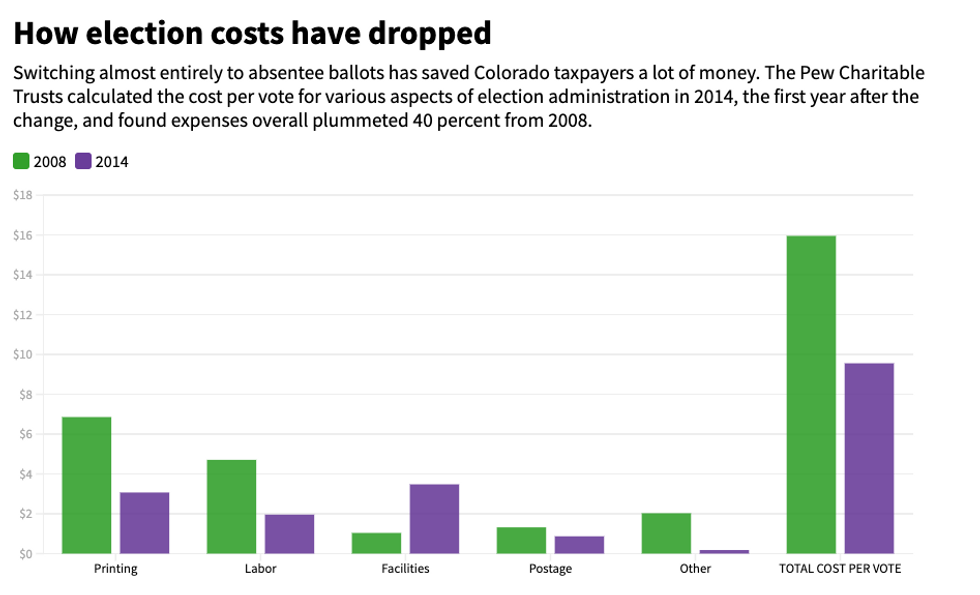

In addition, the cost of running elections in Colorado plunged 40 percent after the switch — to $9.56 for every vote cast in 2014, down from $15.96 six years before, according to a 2016 study by the Pew Charitable Trusts. Much of the savings came from reduced labor costs after the elimination of thousands of traditional precinct polling places in favor of about 350 voting centers.

Source: Pew Charitable Trusts

Source: Pew Charitable Trusts

Pew's survey of 1,500 Coloradans found 95 percent who mailed ballots were satisfied with their voting experience. Two-thirds said they returned their ballot in person, a figure that has grown slightly in subsequent elections. The reason is convenience: Most said a voting center or drop box was less than 10 minutes from home.

Low rejection, but still a partisan split

Colorado's system is further smoothed by its reliance on honesty. Unlike 11 states, no witness is required. Voters' signatures on the envelopes are their bond. The result has been a very low rate of ballot rejection — less than 1 percent in each of the past three general elections.

In 2016, according to statistics reported to the federal Election Assistance Commission, three-quarters of the ballots that got tossed, or about about 20,000, were because the signature did not match the handwriting on file. (The state relies mainly on software that banks use to verify signatures, backstopped by bipartisan pairs of election judges.)

Signature matching is of keen interest to those who suspect universal mail voting makes election fraud easy. They are overwhelmingly Republicans who suspect foul play by the Democrats — President Trump, most famously, but also the legislators who fought the switch back in 2013.

Their concerns were muted somewhat the next year, when Republican Cory Gardner scored an upset Senate victory and the GOP also won three of the other four statewide races. (Gardner is now an underdog as he seeks a second term against John Hickenlooper, the previous governor who signed the vote-by-mail law.)

And there has not been any credible allegation of a voting fraud scheme in the seven years since. While the state heard about 62 scattered cases of potential double voting two years ago, out of 2.6 million votes cast, no charges have been filed. The most memorable case of fraud was in 2016, when former state GOP Chairman Steve Curtis was sentenced to four years probation for forging his ex-wife's signature and sending in her ballot.

Gardner and the congressman who currently heads the state party, Ken Buck, are now among the many Republicans who speak well of the system. So is Wayne Williams, who lost the secretary of state's job to Griswald two years ago, and who sometimes finds himself in the awkward position of defending mail-in voting when fellow Republicans around the country parrot Trump's unfounded claims.

"Mail-in voting is safe if you have the proper processes in place," Williams said earlier this year. "Our state's system is an example of how things can be kept secure."

The rolls are often checked

Protecting the voter database from hacking and keeping the rolls up-to-date are critical to making mail-in elections credible. That's because having lots of ballots mailed to people who have died, moved away or gone to prison is both inefficient and creates at least the possibility of blank ballots being harvested and abused.

Like many states, Colorado keeps its lists up to date by tapping into the Postal Service's national change of address database, double checking against the state tax and drivers' license records and looking at Social Security files for voters who have died. It is also part of the Electronic Registration Information Center, a consortium of 30 states that share registration information to improve accuracy of the rolls.

Part of proper registration list maintenance is sending notices to people who appear to have moved. Colorado has been among the most aggressive states in this regard, the federal EAC says, although this month the conservative group Judicial Watch filed a federal lawsuit alleging the state had done too little to keep its voter database up to date.

Keeping up means looking ahead

Once Colorado established its new system, it didn't stop tinkering with voting procedures — continuing to maintain a reputation on the cutting edge of efficiency and security.

The state in 2017 became the first to use risk-limiting audits to check returns. Considered the best method for verifying results, these audits involve double-checking ballots in scientifically selected quantities and locations. The findings can then be said to accurately reflect what happened statewide.

Back in 2009 Denver became one of the first places allowing voters to track the travels of their mail-in ballots online. Those systems are in most states now. But in May Colorado became only the fifth state to automatically send text or voice notifications to voters as their ballots move through the process.

This month the state deployed a system permitting voters to use the phone to resolve rejections of ballots for possible signature problems — by sending a text, maybe with a photograph attached, confirming the handwriting and the person wielding the pen are authentic.

The deployment of official ballot drop boxes continues to expand. This year the total will be 368 — a 20 percent increase from two years ago. There will be one box for every 9,400 voters. (In the largest county in Texas, by contrast, for now there is a single dropoff site for 2.4 million voters.) Colorado law requires the boxes be kept under 24-hour surveillance either in person or via video surveillance.

Colorado is one of only four states that permit officials to process ballot envelopes as soon as they arrive at county election offices — checking signatures, removing the ballots and preparing them to get fed into tabulating machines. And the state sets the second earliest moment (after Florida) when the actual counting may begin — 15 days before Election Day, which was Monday.

Working under threat

While the system retains a mostly pristine image nationwide — nearly every state has contacted Colorado looking for advice this year — some cracks have begun to show in the mostly bipartisan unity, especially among the secretary of state and local election officials, that has been a hallmark of the state's success.

At 36, Griswold is much younger, more aggressive and more media savvy than some of her predecessors as the top elections official. She has responded to Trump directly on his turf — Twitter — and made numerous appearances on national cable TV shows often responding to Trump's vote-by-mail attacks.

Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold

Aaron Ontiveroz/Getty Images

Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold

Aaron Ontiveroz/Getty Images

The result has been an increase in grumbling from county clerks and election directors, Republicans and Democrats alike, exposed when Colorado Public Radio recently published emails from some of them. One theme was frustration over Griswold pushing for additional election law changes they did not support, a departure from past practice.

Griswold makes no apologies for aggressively defending the state's voting system and pushing additional improvements. Some say her critics have been fueled by sexism. What becomes of this disharmony after the election, and what impact it has on how Colorado's elections are conducted and perceived in the future, remains to be seen.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift