It’s an election year. Should churches have political candidates speak at Sunday services? Should clergy tell congregants how to vote? Should congregations organize political rallies or get-out-the-vote efforts? What are the proper lines for religious involvement in politics?

Podcast: God Squad: Souls to the polls?

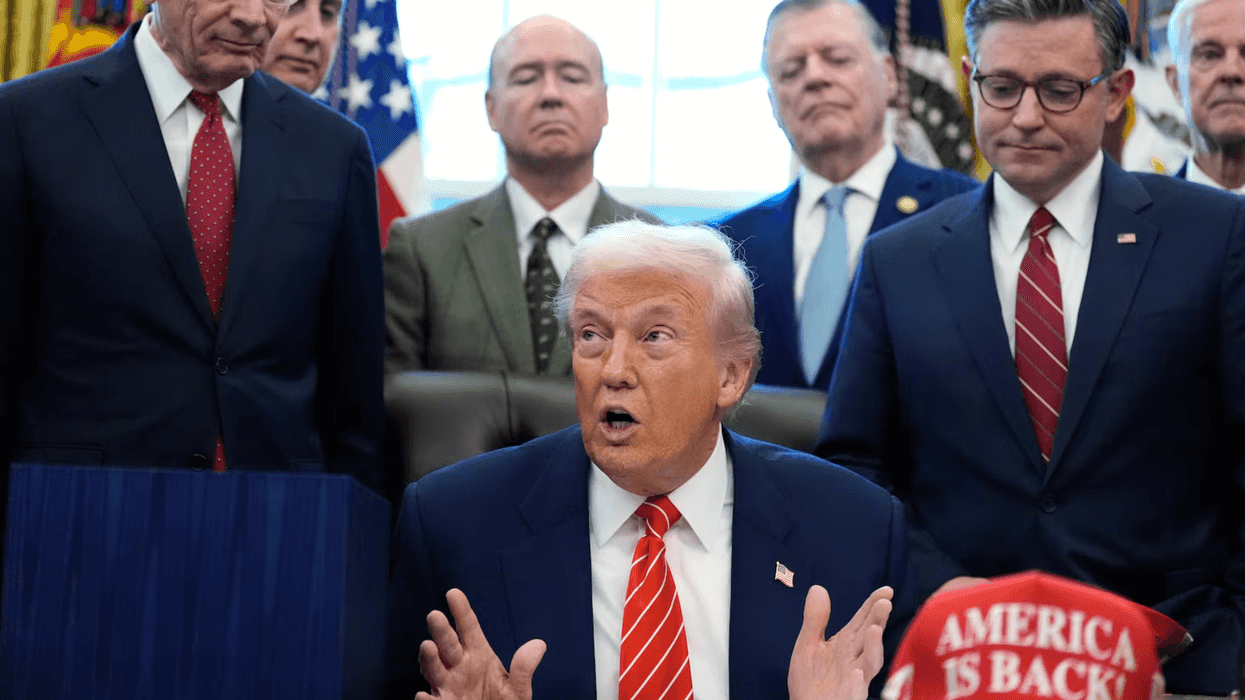

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room