Roath is a voting rights attorney who recently ended his term as Common Cause Massachusetts board chairman.

Across the country, democracy is in retreat. By the end of last month, legislatures in 43 states were considering bills that would make it harder to vote — more than 250 of them, or seven times as many as a year earlier. This week, Iowa became the first state since the 2020 election to enact fresh election restrictions, a sweeping package focused mainly on curbing mail-in voting.

While the phenomenon has touched virtually every part of the country, the potential rollback of voting rights is most acute in states where Republicans hold legislative power but President Biden won in November. Lawmakers in these states are leveraging widespread but discredited conspiracy theories about the results of the election to fuel a new wave of race-targeted voter suppression. The Georgia House and Senate, for example, have both passed separate sweeping voter suppression bills that, among other things, target turnout efforts by Black churches. In Arizona, legislators are considering a range of bills that would constrain access to mail-in voting and disenfranchise the most vulnerable.

In short, members of an aggrieved minority are attempting to restrict voter access after an election with results disappointing to them. That is nothing new: Our history is replete with groups attempting to accomplish similar goals, often with success.

Federal legislation would be an obvious and appropriate response, but it is far from clear Congress will take action. Last week the House passed the For the People Act, a comprehensive bill that would impose new nationwide registration and access standards and guarantee same-day registration, among many other objectives. But it is unlikely to pass unless the Senate weakens the filibuster and allows the law to pass with the bare majority that Democrats currently hold.

So, what then?

In the regrettably likely event that Congress is unable to pass sweeping voting rights legislation, advocates and engaged citizens should look to lift up and support the pro-voting-rights efforts taking place right now across the country.

The voting rights progress being achieved in other states — red, blue and purple — amounts to a growing counter-narrative to the concerted disenfranchisement we see playing out in Iowa, Georgia and Arizona.

Three of the brightest spots on the voting rights heat map are Virginia, Kentucky and Massachusetts.

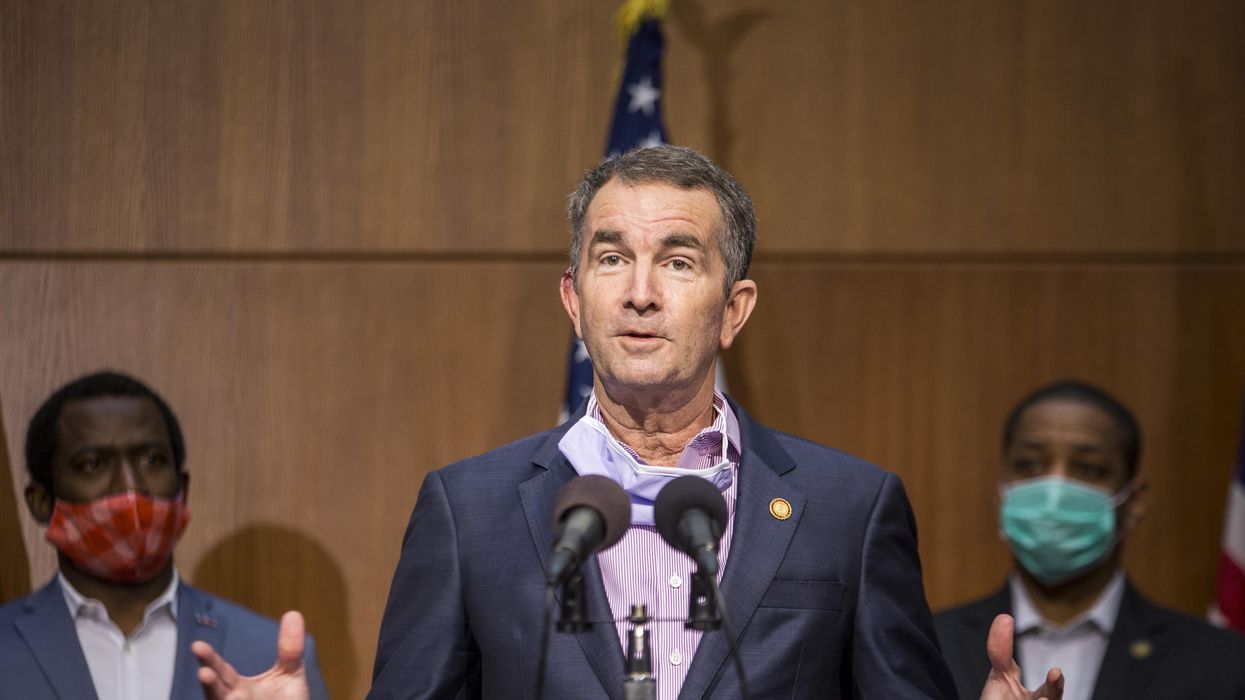

In Richmond any day now, Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam will sign a landmark law intended to create a Virginia mirror of the federal Voting Rights Act at the height of its effectiveness.

It replicates many key features of the national law and back-fills many of the provisions that, at the federal level, have been eroded by litigation and Supreme Court decisions. The innovative bill would grant the state's attorney general new authorities to police local elections changes designed to suppress the vote and prohibit local governments from establishing voting systems (such as "at large" elections) that disproportionately exclude minority voters.

Last year, for the first time ever, people in Kentucky could cast their ballots by mail or vote early and in person if they were concerned about contracting the coronavirus at the polls. Unsurprisingly, these reforms were popular and precipitated record turnout in the fall. Rather than rolling back these successful measures, Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear and the Republicans in charge of the General Assembly appear aligned in favor of extending them indefinitely — which would mean long-term progress on voter access in the South.

Then there's my home state, which is widely perceived as both blue and progressive but has traditionally been a laggard on voting reforms. Apart from emergency measures enacted during the pandemic last year, Massachusetts has no tradition of mail-in voting and has never permitted same-day registration.

But the story here now is much the same as Kentucky's. Thanks to dedicated advocacy and a positive experience with mail-in voting last year, there is widespread consensus that absentee ballots should become an enduring feature of state elections. Democrats in lopsided control on Beacon Hill are considering bills to allow people to register and cast a ballot on the same day along with various other long-sought reforms.

These efforts deserve greater national attention for several reasons.

First, if successful, these reforms would mean that more Americans have more voting options and greater access to democratic institutions. That, in and of itself, is a worthy outcome we should celebrate.

Second, these states can model what meaningful progress on voting rights can look like for the rest of the country. Once successful policies are rolled out, they tend to become popular, and can serve as proof points for advocates in other states. Based on my advocacy experience, it's very persuasive to point out to a lawmaker that 21 other states and the District of Columbia already have same-day registration and then say: "If they can do it, why can't we?" This kind of challenge tends to motivate people.

Finally, issue-based advocacy in the states can set up the playbook for how to effectively push for similar policies in Washington.

There is only so much "model" states can do to counteract voter suppression in other parts of the country. Ultimately, robust federal laws are needed to guard against abuses in a country where your voting rights are vastly different depending on where you live. Action by the states can build momentum for action by Congress — as we've seen in any number of policy areas, from health care access to the criminal code to the minimum wage

So pay attention to what's happening in all the states on voting rights — the good and the bad.

Pushing back against organized voter suppression in one place requires us to push forward in other places. We should be lifting up examples of policymakers, advocates and ordinary citizens who come together to advance the cause of a just, multiracial and well-functioning democracy. They are, in more ways than one, our model citizens.