Having organized last year's grassroots movement ending Michigan's politicized gerrymandering, Fahey is now executive director of The People, which is forming statewide networks to promote government accountability. She interviews a colleague in the world of democracy reform each month for our Opinion section.

Cindi Z.S. Copeland has gone from someone who never voted to someone who spends her free time meeting in libraries, coffee shops and at dinner tables to unite Virginians of all political stripes around improving civic life.

Her life is inspiring and resonates with me on many levels. Neither of us share the same beliefs as some family members, both of us have lost relationships because of such differences and each have stayed involved in politics because we think all people have the right to make their voices heard. We find inspiration from connecting with people from different backgrounds, because you never know if your next conversation is going to transform your life.

Our recent phone conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Fahey: How did you get involved in People?

Copeland: In October 2018 I participated in a focus group for women in the D.C. area who held different political views. Early this year members of our focus group were asked if we wanted to work on a new program bringing together people from up and down the political spectrum to find common ground, talk about why we are so polarized and try to fix it. I said yes and soon became one of The People's co-leaders for Virginia.

Fahey: The People brought about 100 people from all 50 states, with different backgrounds and viewpoints, to Washington in May. What was that like?

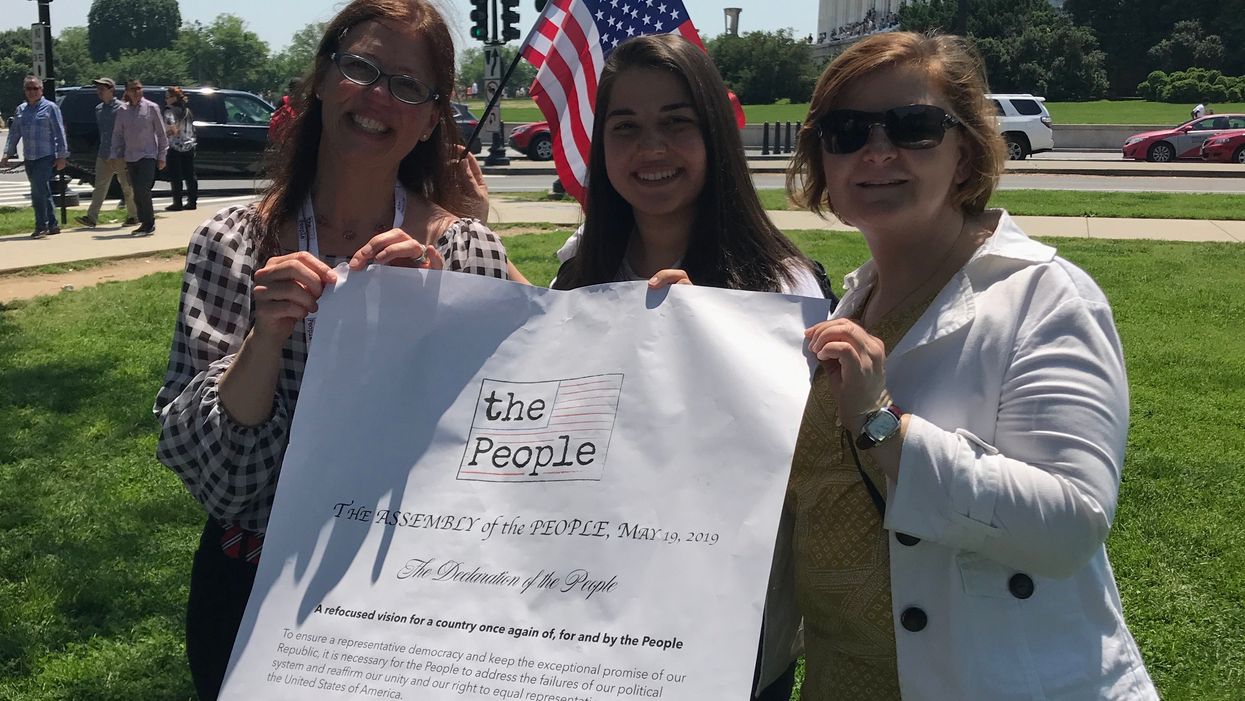

Copeland: It was great meeting people from states I have never been to, hearing what their lives were like and hearing their excitement about getting more involved in fixing what's broken. It was also an exhausting and jam-packed 48 hours with lots of thinking, listening to others and sharing my thoughts! Most exciting was drawing up our People's Declaration with perfect strangers and seeing a final document that — though imperfect — gave us something to move forward with.

Fahey: Is there anyone you met who really impacted you?

Copeland: I was chatting about special education with a guy from Portland, Oregon, on the way to sign our declaration at the Lincoln Memorial. I'm a speech therapist and work with people with autism. He has a friend with a child with autism. At some point it came out I was a Donald Trump supporter and he kind of stopped in his tracks like, "Oh darn, I really liked this person, and now she is saying she voted for Trump?" We started discussing issues and it shifted away from the stuff of real life, but because we first had that conversation on a person-to-person level we were able to be frank in discussing our political ideas. Finding common ground is so important. We need more people who see things differently but help each other anyway.

Fahey: You registered to vote a little later in life and have been inspired to encourage others to do so. Could you share that journey?

Copeland: I did not vote until I was in my mid-40s. I had thought politics was for those with strong stomachs who could tolerate contentiousness and electing people who made promises but didn't often stick to them. I didn't think politics was really for me. I also didn't think I had enough information. I was so busy raising kids, working, doing volunteer work and being active in my church that I didn't think I had time to accumulate the information to really understand the issues. Then I realized I didn't like the increasing polarization, divisiveness and name calling. I decided to get involved and stop saying this is for others to deal with. I have five kids and don't want them to grow up and raise their own families in a society so divided and ugly.

Fahey: Describe the work you are doing on the ground now.

Copeland: We started a listen-learn-action tour this fall in Northern Virginia and will continue to Richmond and southeastern Virginia by early 2020. This is about hearing what people see as needing fixing and exploring solutions together. In our town hall meetings, we present information about how things are broken, talk about what needs to change in civic education and engagement, and hear from attendees about possible solutions.

Fahey: What has it been like to have different political beliefs from family members?

Copeland: When the presidential election was over there was a lot of anger, maybe from people who thought Hillary Clinton would win and did not like what Donald Trump stood for. Trying to share my ideas, mostly on Facebook — why I voted for him and thought it was good he won — I was met with a lot of name-calling and accusations of being racist or anti-immigrant.

Three of my children are in their 20s and at the time of the election all three were in college. I got a feeling they were not very open-minded about hearing from people who thought differently. As a speech therapist, a lot of friends viewed me as a "do-gooder" and assumed I tended towards liberal-minded thinking. They were very surprised to hear I had other beliefs about what I wanted from government. There was a lot of contentiousness. It was very hard. I lost one good friend, my youngest son's godmother.

Being with The People has helped because I've learned skills about building relationships across the aisle and connected with many people who also want to find common ground. It's become easier talking with my big three. I've learned how to be a better listener and share ideas in a way that reflects an understanding that people don't all think the same. Having never really discussed politics before, I am finding my voice.

Fahey: If you were speaking to a high school student or maybe a new immigrant to the country, how would you describe what being an American means to you?

Copeland: America and opportunity are synonymous. I seize any opportunity, which is how I came to The People: I saw the ad, went to the focus group, got the email, and now have a leadership role. To me, being an American is not waiting for someone else to dictate how you should live or what you should do. It's about being a very active member of society who embraces opportunity.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift