Sheehan is professor of political science and international studies at Iona College and the author of "American Democracy in Crisis: The Case for Rethinking Madisonian Government" ( Palgrave Macmillan, 2021)

The fact that our political system is troubled has been widely acknowledged, going back well before the pandemic and the 2020 election. A Pew poll in late 2019 found trust in government had plummeted to a historically low 17 percent. That year more than 60 percent of Americans told Gallup pollsters they have little confidence in the government's ability to address key domestic challenges.

While there is a tendency to blame the malaise on those serving in office, management guru Peter Drucker cautions that what we are witnessing may instead be a "symptom of systems failure." It may be a sign that "the assumptions on which the organization has been built," he says, "no longer fit reality."

Students of American government would be wise to take Drucker's admonition seriously.

The assumption on which our system was built is protectionism, specifically protection of liberty. This is what the Framers saw as the object or purpose of a free state, and it informed almost every decision they made when structuring the government.

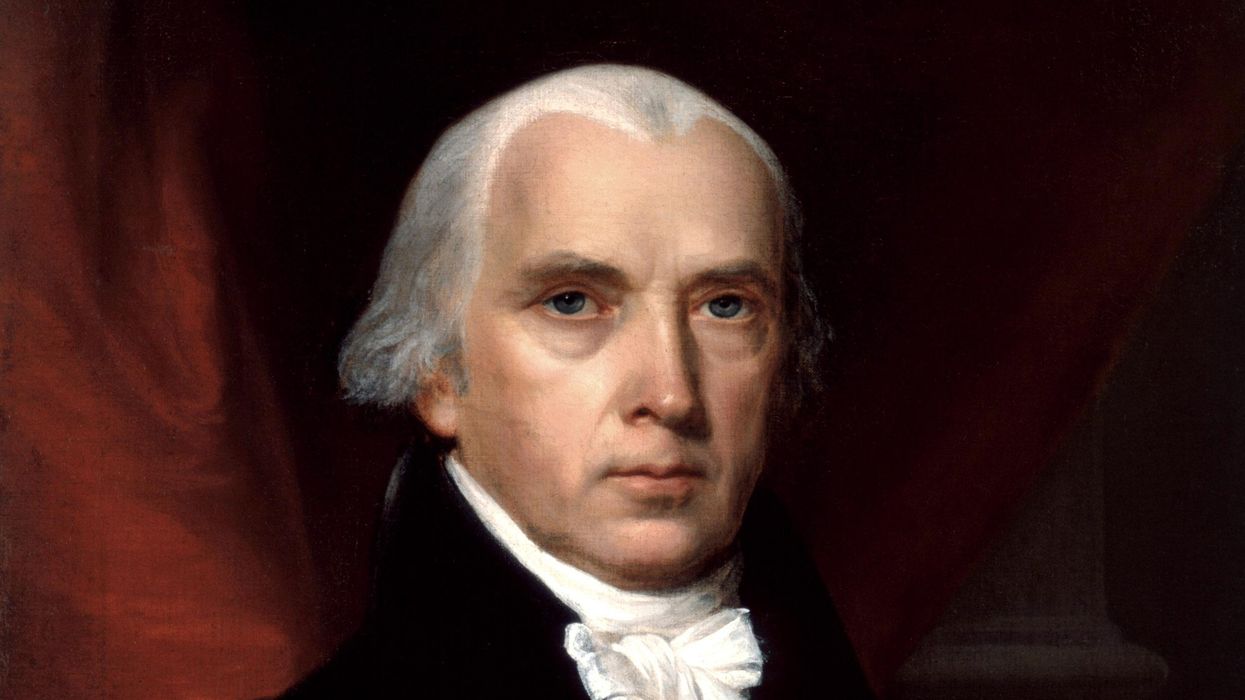

Their commitment to the protection of liberty helps explain why the Father of the Constitution, James Madison, wrote in Federalist No. 10 that the greatest threat to popular government is majority factions. His concern was that majorities might take over the government and use their power to promote interests averse to the rights and liberties of the minority. While majority factions can be animated by a variety of shared interests, the Framers were particularly concerned about factions made up of those without property.

As a result, in drafting the Constitution the Framers went to great lengths to thwart majorities, prevent their formation and minimize their impact. Most importantly they followed Montesquieu's dictate that the best way to protect liberty is to separate power. To this end they adopted our tripartite arrangement, with three equal branches. Not content with that alone, however, they added additional elements including a bicameral legislature and a system of checks and balances, amongst other things.

As the constitutional Convention came to an end, Madison confided in a letter to Thomas Jefferson his concern that new system "will neither effectually answer its national object nor prevent the local mischiefs which everywhere excited disgust agst the state governments."

From our vantage point, it is stunning to consider that Madison's primary concern was that the Constitution had not gone far enough to protect liberty and prevent majority tyranny. Nothing can be further from the truth.

It is not an overstatement to suggest they succeeded too well. In their quest to protect liberty the Framers created a system that guards against all majorities, both those that are oppressive and those that are not.

As a result, throughout history countless measures preferred by majorities have been thwarted, delayed or diluted to the point they are largely unrecognizable. This includes everything from basic civil rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s to more recent common sense efforts to curb gun violence, greenhouse gas emissions and prescription drug prices.

In almost every case, the roadblocks built into the system to prevent tyrannical majorities have prevented success by majorities of all kinds and instead given minority interests outsized influence — from Southern Democrats during the civil rights debates to the National Rifle Association, the business lobbies and the pharmaceutical companies today.

While the Framers may have agreed the purpose of free government is to protect liberty — with the liberty to own property topping that list -- the same cannot be said now. Polling shows Americans do not agree on the proper role of government, divided on questions such as whether the government should do more to solve problems and whether it should take a more active role in improving the lives of citizens.

Even more important than the absence of such a public consensus is that a sizable number seem to have a view almost diametrically opposed to that of the Framers. Whereas in 1787 it may have made sense that the primary end of government was to protect liberty, today many expect more — and some expect a lot more.

But anyone who expects the federal government to be responsive to the majority, accountable and able to address key challenges of the day is bound to be wildly disenchanted with the current state of affairs. While tempting to blame the malaise on the incompetence of officeholders, and to imagine the problem would be resolved if we could only replace them, election after election has shown this is not the case.

Moreover, it misses the fundamental point: The problem is not the ineptitude of those in office, but the system itself.

It is the direct result of something little talked about or understood, but which has profound implications for how we live — what the Framers saw as the purpose of a free state.

Their commitment to protecting liberty explains a good deal about the system they created, as well as what it does and does not do. To safeguard liberty they designed a system for gridlock and stasis. This is why large numbers are frustrated and, as decade after decade the government fails to address key challenges they face. And who can blame them?

By the same token, we cannot be surprised if at some time they reach a boiling point — and decide to tune out, or fight back, or seek salvation from a demagogue or strongman.