Sturner, the author of “ Fairness Matters,” is the managing partner of Entourage Effect Capital.

This is the sixth entry in the “ Fairness Matters ” series, examining structural problems with the current political systems, critical policies issues that are going unaddressed and the state of the 2024 election.

We face complex issues, from immigration to the national debt, from Social Security to education, from gun violence to climate change and the culture war, from foreign policy to restoring a vibrant middle class by ensuring economic outcomes are more balanced and equitable.

Yet, neither party seems to be doing much about any of the political problems and policy challenges plaguing our nation. Instead of working on real solutions, our politicians spend their time and our national resources distracting and dividing us by using every tool at their disposal to retain power. Why is that? As Andrew Yang points out in a recent TED Talk (quoting a senator), “A problem is now worth more to us unaddressed than addressed.” It’s galling until you remember that the Democratic and Republican parties are private, gain-seeking organizations that exist to seek and retain power. As such, we should be wary of political parties because our interests and theirs are not aligned.

But it’s not just politicians and the financial interests that fund them. The media has evolved and devolved over the past 40 years, starting with the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine up to and including the commercialization of the internet in the mid-1990s. Social media has only served to amplify the problem a hundredfold. I think Sacha Baron Cohen rightly concludes that social media has become the “ greatest propaganda machine in history. ”

Most Americans seem to agree that we’ve got a people problem in Washington, D.C. Whether it’s infighting between Republicans and Democrats, or unethical, incompetent or extremist politicians who seem beholden to special-interest groups, it seems to be all about the people involved. You’ll get no argument from me.

So how do we attract more ethical, more competent and less extreme leaders?

The answer lies in the system itself. The system has been designed by the parties to achieve these results. Despite a dismally low 15 percent approval rating, 95 percent of incumbent politicians get reelected. Why is that?

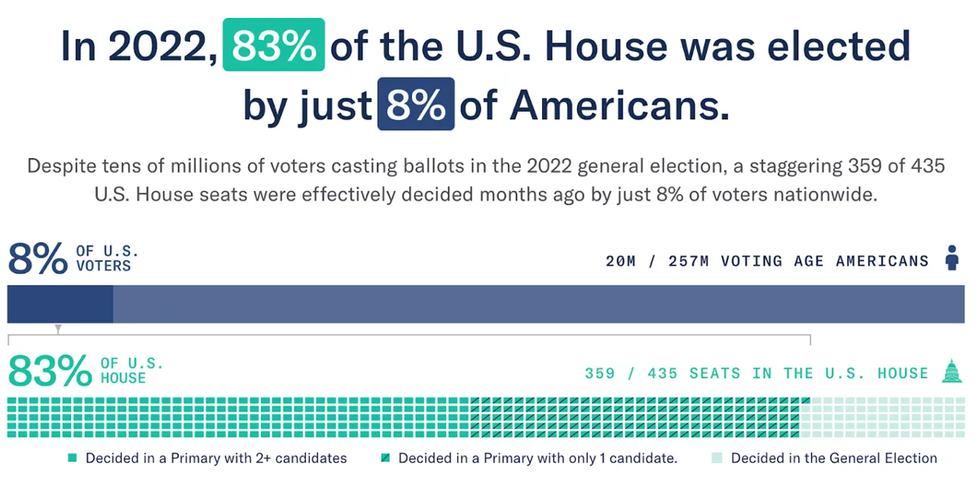

Thanks to partisan gerrymandering, which has become increasingly precise thanks to advances in technology and data science, the outcome in most House districts is predetermined. In those elections, the only real competition is in the primaries, which draw far fewer voters. Especially in closed primaries — where only registered members of a political party may cast a ballot. As a result, a small minority of voters decide the vast majority of congressional elections — fueling political polarization and preventing problem-solving. How can we call ourselves a functioning democracy when the majority of Americans are locked out of those primary elections? That’s why our government doesn’t answer to the will of the vast majority of the governed

The only way to address our people problem is to implement system reforms that bring competition into the political process. It's time to set aside our partisan politics and focus on enacting nonpartisan systemic reforms designed to address some of the fundamental challenges.

The solution(s)

All of this seems daunting. And while there is no magic wand we can waive or any panaceas that will fix the problem overnight, there is a growing consensus that a combination of reforms including, but not limited to, open primaries and ranked-choice voting (also called instant runoff elections) will ensure the system self-corrects over time. Here's how the thinking goes.

Adopt open, nonpartisan primaries

Let's start with some data from Unite America:

91% agree that all voters should be able to vote for any candidate in every taxpayer-funded election

76% agree that candidates should have to earn majority support to win an election

States can adopt nonpartisan primaries — as already used for presidential elections in California, Louisiana, Nebraska, Washington and most recently Alaska — that allow all voters to participate in a single primary with all candidates on the same ballot. The top finishers advance to the general election, where whoever earns majority support wins.

“Nonpartisan primaries give every voter an equal voice, have higher voter participation rates, produce more representative outcomes, and improve governing incentives by ensuring elected leaders are accountable to a broader swath of the electorate,” said Jeanelle Lust of South Dakota Open Primaries.

Voters in South Dakota will have the opportunity, via a ballot question, to switch to nonpartisan primaries when they vote this fall.

End plurality voting

There’s no question that we must end plurality voting. But which system should replace it? Voters recently made a significant change in Alaska, and Nevada may be next.

In 2022, Nevada voters approved Question 3, which proposed replacing party primaries with a single nonpartisan primary where the top five candidates would advance to a general election that uses ranked-choice voting. Because the proposal modifies the state Constitution, it will have to be reapproved by Nevada voters again in 2024 before it can take effect. If it is reapproved, the system would take effect for the 2026 election cycle and be used for all state and federal elections except for president and vice president.

Whether it's top-two ( California and Washington), final four (Alaska) or final five (Nevada), any of these changes is a huge improvement over what the rest of us are forced to use.

Most experts seem to agree that ranked-choice voting, which is used for state primaries and all federal elections in Maine, as well as state, congressional, and presidential general elections in Alaska, is the most viable and fair alternative. In addition to those two states, RCV is used for local elections in 47 cities including New York, Salt Lake City, Seattle and Cambridge. It is also used by the Virginia, Utah, and Indiana Republican parties in state conventions and primaries. And, RCV is gaining in both red and blue states, including Oregon, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin and Vermont.

We need systemic reform

Absent reform it will become harder and harder to elect representatives who demonstrate common sense and break from the extreme partisanship that is tearing our country apart. This is a topic well covered by Katherine Gehl:

“The ‘broken’ US political system is actually working exactly as designed. Examining the system through a nonpartisan lens, she makes the case for voting innovations, already implemented in parts of the country, that give citizens more choice and incentivize politicians to work towards progress and solutions instead of just reelection.”

Any goal to upend the system, buck precedent and break down the extraordinary power of the Republican and Democratic establishments is not something that could possibly happen without courage and risk. And these reforms do not favor one party over another. Consider Cambridge University’s article, “ Why Donald Trump Should Be a Fervent Advocate of Using Ranked-Choice Voting in 2024."

“Our evidence clearly shows that third parties have the potential to hurt either of the two main parties; however, in 2020, it was Donald Trump who was hurt the most, although not consequently. Second, some reformers believe that ranked-choice voting benefits the Democrats; again, we show that—all else being equal—in the 2020 presidential election, it was the Republicans who would have benefited by the change in rules because the majority of third-party votes went to the Libertarian candidate, whose voters prefer Republicans over Democrats 60% to 32%.”

So do not concern yourself with partisan politics in considering this agenda. At almost every level of government, progress and civility have been thwarted by partisan actors who work for political parties instead of the people. It’s time to end the divisiveness.

There are some incredible organizations working on rebalancing the scales, like RepresentUs, Unite America, Open Primaries, FairVote, Rank the Vote, American Promise, Protect Democracy, Veterans for Political Innovation and Represent Women — all of which are building grassroots infrastructure to support efforts around the country as we work to build a democracy where voters come first.

We have the opportunity to break the cycle, to move beyond the status quo and to champion the voices of those who've been left out of the partisan conversation.

The more I get involved with these amazing organizations, the more I have renewed hope for America!