Collins is a professor of legal studies and political science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Ward is a professor of political science at Northern Illinois University.

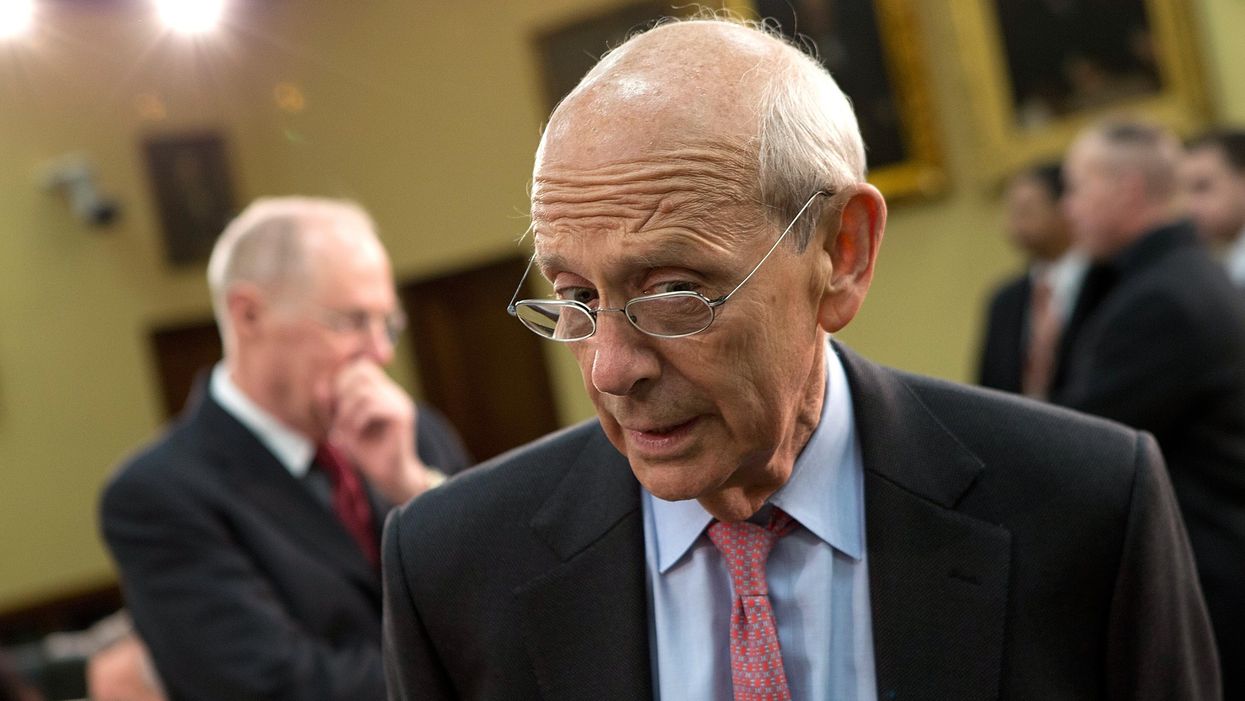

Pressure on Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer to step down will likely grow now that the court's session has ended.

Breyer, 82, joined the court in 1994. His retirement would allow President Biden to nominate his successor and give Democrats another liberal justice, if confirmed.

Supreme Court justices in the U.S. enjoy life tenure. Under Article 3 of the Constitution, justices cannot be forced out of office against their will, barring impeachment. This provision, which followed the precedent of Great Britain, is meant to ensure judicial independence, allowing judges to render decisions based on their best understandings of the law — free from political, social and electoral influences.

Our extensive research on the Supreme Court shows life tenure, while well-intended, has had unforeseen consequences. It skews how the confirmation process and judicial decision-making work, and causes justices who want to retire to behave like political operatives.

Problems with lifetime tenure

Life tenure has motivated presidents to pick younger and younger justices.

In the post-World War II era, presidents generally forgo appointing jurists in their 60s, who would bring a great deal of experience, for less experienced nominees in their 40s or 50s who could serve on the court for many decades.

And they do. Justice Clarence Thomas was appointed by President George H.W. Bush at age 43 in 1991 and famously said he would serve for 43 years. There's another 13 years until his promise is met.

The court's newest member, Donald Trump's nominee Amy Coney Barrett, was 48 when she took her seat in late 2020 after the death of 87-year-old Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Ginsburg, a Clinton appointee who joined the court at age 60 in 1993, refused to retire. When liberals pressed her to step down during the presidency of Democrat Barack Obama to ensure a like-minded replacement, she protested: "So tell me who the president could have nominated this spring that you would rather see on the court than me?"

Partisanship problems

Justices change during their decades on the bench, research shows.

Justices who at the time of their confirmation espoused views that reflected the general public, the Senate and the president who appointed them tend to move away from those preferences over time. They become more ideological, focused on putting their own policy preferences into law. For example, Ginsburg grew more liberal over time, while Thomas has become more conservative.

Other Americans' political preferences tend to be stable throughout their lives.

The consequence is that Supreme Court justices may no longer reflect the America they preside over. This can be problematic. If the court were to routinely stray too far from the public's values, the public could reject its dictates. The Supreme Court relies on public confidence to maintain its legitimacy.

Life tenure has also turned staffing the Supreme Court into an increasingly partisan process, politicizing one of the nation's most powerful institutions.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Supreme Court nominees could generally expect large, bipartisan support in the Senate. Today, judicial confirmation votes are almost strictly down party lines. Public support for judicial nominees also shows large differences between Democrats and Republicans.

Life tenure can turn supposedly independent judges into political players who attempt to time their departures to secure their preferred successors, as Justice Anthony Kennedy did in 2018. Trump appointed Brett Kavanaugh, one of Kennedy's former clerks, to replace him.

The proposed solution

Many Supreme Court experts have coalesced around a solution to these problems: staggered, 18-year terms with a vacancy automatically occurring every two years in nonelection years.

This system would promote judicial legitimacy, they argue, by taking departure decisions out of the justices' hands. It would help insulate the court from becoming a campaign issue because vacancies would no longer arise during election years. And it would preserve judicial independence by shielding the court from political calls to fundamentally alter the institution.

Partisanship would still tinge the selection and confirmation of judges by the president and Senate, however, and ideological extremists could still reach the Supreme Court. But they would be limited to 18-year terms.

The Supreme Court is one of the world's few high courts to have life tenure. Almost all democratic nations have either fixed terms or mandatory retirement ages for their top judges. Foreign courts have encountered few problems with term limits.

Even England — the country on which the U.S. model is based — no longer grants its Supreme Court justices life tenure. They must now retire at 70.

Similarly, although many U.S. states initially granted their Supreme Court judges life tenure, this changed during the Jacksonian era of the 1810s to 1840s when states sought to increase the accountability of the judicial branch. Today, only Supreme Court judges in Rhode Island have life tenure. All other states either have mandatory retirement ages or let voters choose when judges leave the bench through judicial elections.

Polling consistently shows a large bipartisan majority of Americans support ending life tenure. This likely reflects eroding public confidence as the court routinely issues decisions down partisan lines on the day's most controversial issues. Although ideology has long influenced Supreme Court decisions, today's court is unusual because all the conservative justices are Republicans and all the liberal justices are Democrats.

In April 2021, Biden formed a committee to examine reforming the Supreme Court, including term-limiting justices. To end the justices' life tenure would likely mean a constitutional amendment requiring approval from two-thirds of both houses of Congress and three-fourths of U.S. states.

Ultimately, Congress, the states and the public they represent will decide whether the country's centuries-old lifetime tenure system still serves the needs of the American people.