Top Democratic presidential candidates appear universally opposed to the major Supreme Court decisions that have recently reshaped American politics but are split on whether or even how to reshape the high court itself.

But controversial Supreme Court decisions, such as loosening the reins on campaign finance, allowing for extreme partisan gerrymandering and gutting the core of the Voting Rights Act, have at least some Democrats talking about overhauling the judicial branch.

In the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt — another Democrat unhappy with a conservative-majority high court — championed legislation to add an additional six justices to the bench. His plan, which was dubbed "court packing," got nowhere in the end.

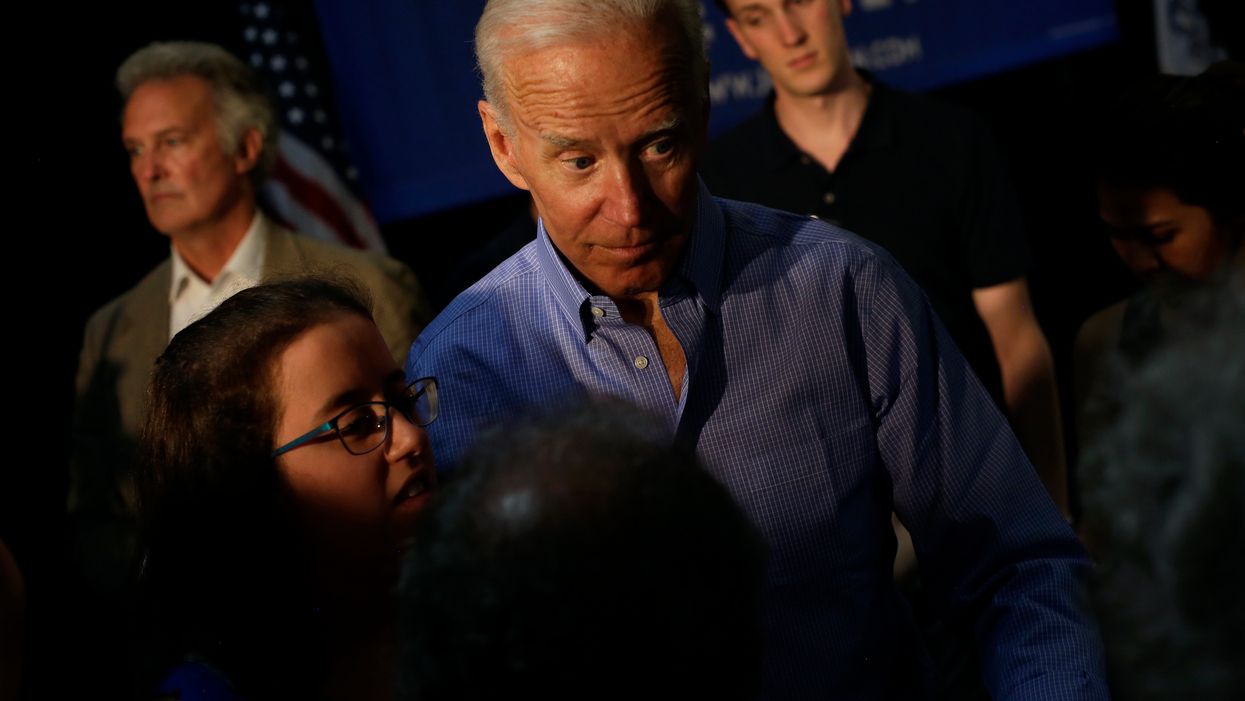

At a campaign event Friday in Iowa, Democratic frontrunner Joe Biden said he opposed expanding the number of justices.

"No, I'm not prepared to go on and try to pack the court, because we'll live to rue that day," the former vice president told the Iowa Starting Line.

Other Democratic hopefuls have offered other plans to remake the Supreme Court, where the majority of five conservatives could remain a long-term obstacle to lasting changes in the name of democracy reform.

During the first Democratic debates, Bernie Sanders said he opposed FDR-style court packing and offered an alternative.

"We've got a terrible 5-4 majority conservative court right now," the Vermont senator said. "But I do believe constitutionally we have the power to rotate judges to other courts and that brings in new blood into the Supreme Court."

That idea isn't new — nor is it a radical liberal one.

Seven years ago, a University of Missouri law professor named Josh Hawley wrote a piece for National Affairs titled "The Most Dangerous Branch." He argued there was nothing inherently unconstitutional about rotating judges from the lower federal appeals courts through the Supreme Court. Now Hawley is in his first year as a Republican senator from Missouri, with a seat on the Judiciary Committee.

"Congress could stipulate that the Supreme Court be staffed with nine life-tenured judges drawn at random from the courts of appeals. These judges would serve on the Supreme Court for a term of several years, and then return to their original appointed posts on the lower appellate courts, to be replaced by another group of nine drawn by lot," he wrote in 2012. "Justices would thus acquire incentives for caution and moderation rather than judicial aggrandizement."

Among top-polling Democrats, only Sanders has mentioned rotating judges. Others in the presidential field have less defined strategies to mollify progressive voters upset by recent Supreme Court rulings – but few have ruled out court packing.

In March, both Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris toldPolitico they were open to the idea.

"It's a conversation that's worth having," Warren, a Massachusetts senator, said.

Harris, a senator from California whose polling has improved significantly since the first debate, said "everything is on the table." Harris also said she's "open" to another reform idea: applying term limits on justices, the pros and cons of which are debated in legal circles.

Biden, whose campaign website doesn't propose any changes in the judiciary, told a woman in Iowa last week that he opposes term limits for Supreme Court justices as well as court packing.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., appears to be the only candidate regularly polling as a top-five contender who explicitly supports growing the size of the Supreme Court. He has called for a court of 15 justices, with 10 "confirmed in the normal political fashion" and the others promoted from the lower courts "by unanimous agreement of the other 10."