Berman is a distinguished fellow of practice at The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, co-editor of Vital City, and co-author of "Gradual: The Case for Incremental Change in a Radical Age." This is the 11th in a series of interviews titled "The Polarization Project."

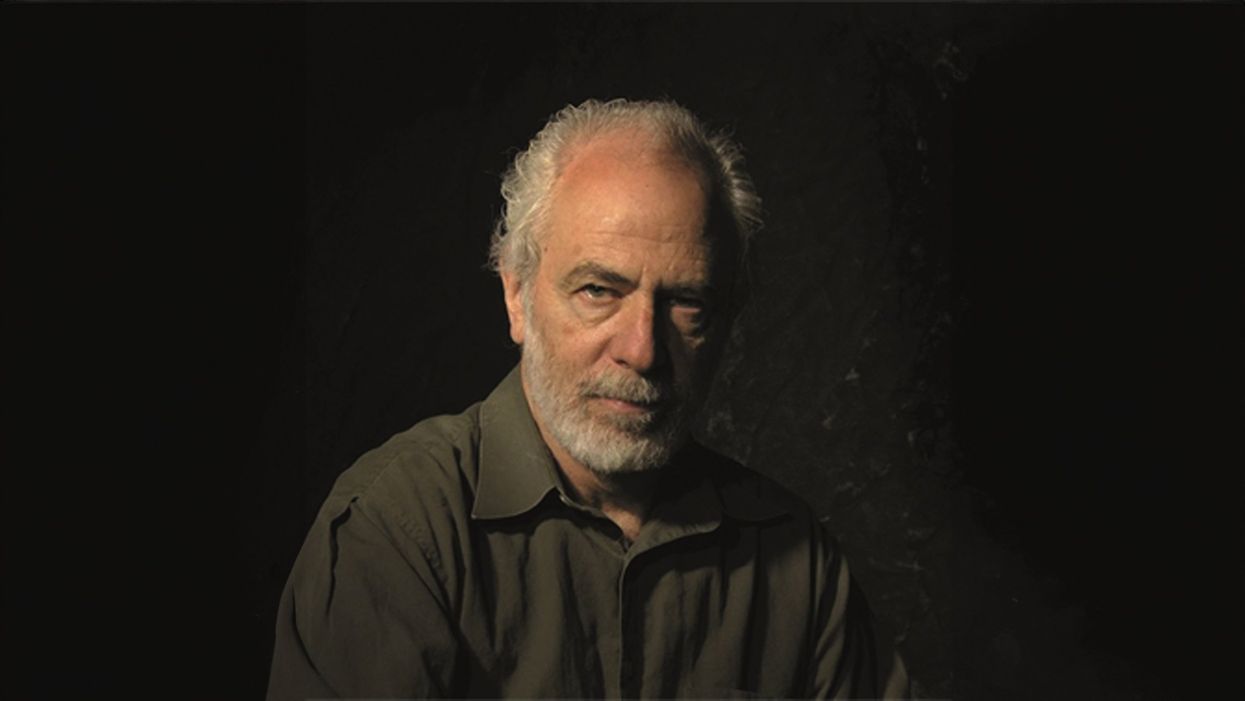

Is the United States on the brink of a civil war? Few people are better placed to answer that question than historian Richard Slotkin.

Slotkin, an emeritus professor at Wesleyan University, has devoted his career to the study of violence and American history. In an award-winning trilogy of books (“ Regeneration Through Violence,” “ The Fatal Environment,” and “ Gunfighter Nation ”), Slotkin explained how the myth of the American frontier — the idea that violence against a racialized other must be employed to conquer the wilderness and make way for civilization — has been used to justify government action across the history of the United States.

In his latest book, “ A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America,” Slotkin turns his attention to contemporary politics. He is alarmed by what he sees.

According to Slotkin, the culture wars are not a trifling distraction but rather a fundamental clash between conflicting versions of the United States. While he thinks a “war between the states” like that of 1861-1865 is unlikely, he does believe that the country is on the brink of entering a death spiral. Looking forward, he predicts a future of renewed political violence, plagued by “terrorism, urban uprisings, and intercommunal violence of the kind that has plagued Israel and Northern Ireland.”

I spoke with Slotkin about the importance of the stories we tell ourselves about American history and how the past influences contemporary culture and politics. The following transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Greg Berman: There are a lot of theories about why the U.S. feels so divided right now. Some people point the finger at inequality. Others at globalization or technology. Your book makes the case that a big part of what's happening is that we are suffering through a loss of a unifying national story. Walk me through the argument. How did that come to be? Why is that so important?

Richard Slotkin: Well, the loss of the national story is linked to the other things that you mentioned. When we talk about a national story, we're talking about a story that leads people to identify themselves with the nation-state and to see the government as an extension of themselves in some way. What has happened is that we've been hit with a series of self-reinforcing crises that have called into question our feelings about the government and our feelings about belonging to America.

One of the big ones obviously is demographic change. Then you get the globalization of the economy, where workers get a lower share of income, less dignity, less job security and so on. And then compounding all of that, you have a series of crises which really called into question the government's ability to understand, to make sense of, or to deal with these problems — the dot-com crash, the savings and loan crisis, the Great Recession. These crises really distorted the economy. And the government responded generously to the bankers and stingily to the rest of the people who were suffering. And then you had Covid, which, again, struck people unevenly. The government's response was irrational and untrustworthy, partly because Donald Trump was in charge of it. You put all of that together and you have a real crisis of confidence in government.

GB: You identify four principal myths that have undergirded the U.S. How did you arrive at these four?

RS: What I looked for were stories that perennially are invoked to explain the existence and operations of the nation-state. And it's pretty clear that the frontier myth is the oldest one and that the founding has to be the second one. The Civil War, and the various ways of interpreting it, are added to the mix because the Civil War tests the question whether the nation can continue, and if it continues, in what form should it continue? And then the final one, the myth of the Good War, is the one that really shaped my consciousness and shaped America's approach to foreign policy and domestic policy after the 1940s. The myth of the Good War is the idea of America as the liberator nation, as a multiethnic democracy fighting against totalitarian and racist powers.

GB: You have argued that the U.S., more so than other nations, is beholden to its mythology. Why is that? Why are we different in that respect?

RS: Because Americans have always been of such different ethnic, religious and racial origins. All of the modern nation-states have had to overcome ethnic and religious difference and, in some cases, linguistic difference as well. But it was much simpler to unite French-speaking people behind the idea of France when they all look like French people. It is much harder to unite a nation which has included, since the very beginning, English people, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Scots, Africans, Native Americans — and then expanding as we go along to include every nation on the globe as potential citizens. So what is it that enables people of such diverse origins to think of themselves as Americans? We are born to our communities and our families. We have to learn to think of ourselves as belonging to this larger community called America, which is not really visible to us most of the time. It's known to us through the stories that tell us we belong to America.

GB: I recently came across a quote from Ernest Renan, the French historian, who said that forgetting and historical error are essential elements in the creation of a nation. I'm wondering whether it is possible to have a 100 percent truthful national story.

RS: I think it's possible to have one that is true in principle. When we talk about the translation of history into myth, we're talking about a simplification process in which a complex, multifaceted reality is reduced to a story with a few characters in it. So there's always going to be some forgetting, some elimination. But I do think that it is possible for a national story to be one that includes the dark side of our history. And in fact, the overcoming of the dark side is a great story. It's a story we tell all the time in popular culture and classical literature.

Take, for example, the way we tell the story of the Civil War. In what I call the liberation version of the story, we don't deny the existence of slavery. We don't deny the evil that slavery was, but we tell the story of how that evil was overcome through struggle. Or take the civil rights movement and the story of Martin Luther King. It's not the story of going from the Garden of Eden to the Garden of Eden. It's the story of the overcoming of the dark side of American life. So I do think that myths can and do incorporate some notion of the darkness and the overcoming of the darkness.

For Americans, the question is, how much will we admit to what we've done wrong on the issue of race? How much will we talk about what we have done wrong in terms of exploiting the environment? How much will we talk about what we've done wrong on the exploitation of labor? There have been moments in the past where we've done fairly well with that. And I think it's possible to do that again.

Let me just also say that whether it's possible or not, it's necessary, because if the story you tell about the nation is too fairytale positive, in the end, it will fail to produce belief. People won't believe that America is always good, always has been good and never did anything wrong.

GB: Sure, but isn't the flip side true as well, that if you tell a story about the country that is too negative — that it's just been 400 years of unremitting racial oppression — that you also won’t generate a sense of positive American identity?

RS: You can certainly tell the story as 400 years of unremitting racial oppression. And, yes, that version fills people with disgust. But that's not the truth. The truth is that as powerful as the exploitation was, there were always people who fought against it. Even in America’s worst episodes, there were always people who were working for the good. And I think if you want people to identify in a positive way with our history, and also to see politics as a place capable of producing good, you have to tell the story in such a way that those struggles can be seen.

GB: Given all that, I'm curious about your reaction to the 1619 Project.

RS: I thought that it was uneven. As a thought experiment, it was very interesting because it does change your view of history if you look at it from the perspective of slavery and the people who came here as slaves. My own view, though, is that the beginning of American history is not 1619, it's 1586, it's Roanoke, it's the beginning of the confrontation with the Indigenous people. It's the foundation of a settler state. That's really the core of things.

GB: I don't know that moving the founding date to 1586 leads to a more optimistic reading of our history.

RS: Have you read “ Native Nations ”? The book basically argues that, as settler-Indigenous relationships developed, there were possibilities for mutual accommodation, some of which were actualized and some of which failed for want of good faith support. I certainly don't want to sugarcoat that history, but I do insist that it was never all one way. There were always possibilities in that history for a different turn of events.

The point of myth is not simply that it's a way of conceptualizing the past. It's about using the past to create an action script for taking positive action in the present. That's the point of mythmaking. And that's why I say that the way you tell the story has to include the possibility for good outcomes. Whether they were realized or not, they existed.

GB: Kurt Andersen's book, “ Fantasyland,” makes the argument that the U.S. has always been a place of religious zealots, hucksters and con men and that a significant portion of Americans have always been untethered from reality at some level. Looking through that prism, I’m wondering whether our current moment is a departure from the norm, or is it a return to the norm of American history?

RS: Well, I wouldn't call it a return to the norm. What Andersen is describing is certainly an aspect of our culture. Hucksterism, grandiosity, narcissism … that's a part of the American story. But I think that we're currently in a moment in which different visions are being asserted.

What I call the MAGA vision, the right-wing culture war vision, really starts in the 1990s. Look at Pat Buchanan's primary campaign in 1992 against George H. W. Bush, where he was basically speaking for conservatives who felt that Ronald Reagan had failed as a cultural conservative, that he had done nothing to advance the values of white Christians. That was the start of the sense of racial grievance, the sense that white people are being discriminated against.

Then you get the 2010 midterm election, in which the Tea Party comes to the fore with a very powerful reaction against [Barack] Obama's presidency and the notion of the nation becoming a majority-minority country. It's also in that period that you get a deeper radicalization of the gun rights movement where it really begins to solidify around a kind of anti-government ideology, the idea that the purpose of the Second Amendment is to arm citizens for possible resistance to the government. That becomes openly stated under Obama.

GB: Violence is a theme that runs through all of your work. Why is America so violent? Is this a congenital defect of our national character?

RS: I think it is. It's not that other cultures are not violent. It's that we have given a peculiar license to the individual right to use deadly force and violence. It's there from the start of the settler state — the need for violent self-defense on the border. You can see it in our acceptance of vigilante justice, not just on the frontier, but in the Jim Crow South. You can see it in this whole notion of the gun as private property that you have an absolute right to use however you want. It's our extreme notion of individualism coupled with a history in which violence by individuals has played a central role.

GB: Speaking of vigilante justice, one of my favorite parts of your book was your description of the period from 1870 to 1920, which you call the Age of Vigilantism. Are there lessons that we can learn from that era that might help us now?

RS: The Age of Vigilantism was very complex. You had the violence of lynch mobs in the Jim Crow South. You also had an extremely violent labor movement in which private, mercenary armies were used against labor organizers and in which workers armed themselves to resist these anti-labor vigilantes. We came out of that era in part through the Great Depression and the establishment of the New Deal.

What you get, starting in the 1930s, was a legal regime that offered labor some protections from violence. It wasn’t complete, but it was far more than had existed before. You also get a legal regime that put a stop to some of the causes of lynching in the South. The New Deal was the key to ending the Age of Vigilantism because it led to a government in which people were willing to place greater reliance than in their private use of arms.

GB: You have highlighted the way that race, or fear of an increasingly diverse country, has motivated a powerful reaction on the right. But then I look at the recent polling numbers for Trump, which suggest that he's doing better than any Republican presidential candidate has done in a long time with Black voters and Hispanic voters. I'm wondering how that squares with your analysis.

RS: I don't really try to get into the details of electoral politics. There are so many factors that cause small percentage shifts one way or another in an election. Certainly, the cultural conservatism of many Blacks and Latinos might lead them to be attracted to the culturally conservative aspect of the MAGA program. And the fact that the Democrats haven't been able to fulfill their program of racial reform inevitably leads to some disillusion. In general, I don't think that the kind of analysis that I'm doing can explain things at that micro level.

What I see is a larger pattern in which a significant percentage of the population is devoted to a story of America as a great White whristian nation corrupted and overrun by a racial and ideological enemy. A significant percentage of the national population, and a majority of Republicans, have adopted that worldview — or at least effectively endorsed it. And that really is, I think, the most critical issue in the present moment. Because even if that school of belief represents a minority of the national population, through their control of the Republican Party, the program that they've adopted is a serious danger to the way American politics and society are organized.

GB: Your version of recent political history points the finger at the Koch brothers, Grover Norquist, the NRA and a host of malevolent actors on the right. But reading your book, I found myself wondering why you hadn’t offered a similar account of the left.

RS: I've been accused of being basically a flack for the Biden administration. There may be some truth to what you say. But is there really a fair comparison between the left and the right? So Hillary Clinton said “ basket of deplorables ” and some liberal college students have said some fairly outrageous things. But what is the left-wing equivalent of the Proud Boys? Which left-wing organizations are arming themselves for violence against the government? What is the left-wing equivalent of Project 2025?

GB: I don’t want to push this argument too hard, but I guess the counter would be that if you look at the institutions of cultural power in our country — from the media to universities to the nonprofit sector to Hollywood — those institutions are not reflective of conservative ideas at the moment. It seems reasonable that this would provoke some kind of a backlash among conservative Americans.

RS: What those institutions are rejecting is the concept of gender, sexuality and family organization that conservatives believe in. I don’t want to minimize it, because that rejection is a serious thing. I think the right is not wrong to react to it, because these things really are a genuine challenge to their fundamental values. If someone considers the legalization of gay marriage to be an insult, there's no way to respond to that.

GB: But that's only part of the story. Part of the conservative backlash is not just about race, gender, family. It's about defund the police. It's about prison abolition. It's about a host of issues where the left has pushed the envelope far beyond what the median voter believes.

RS: I agree with you on that. Defund the police was stupid. But let’s be real: It was a position taken by a minority of voices. The Squad has not moved to defund the police. The police haven't been defunded. Quite the contrary.

GB: In your book, you use the vocabulary “red America” and “blue America” to describe the divide in American life. I understand why you and others use that shorthand. But I think that formulation only describes part of America. In my estimation, there's a huge chunk of America — and I might argue that it is larger than either red America or blue America — that is either blissfully apolitical or ideologically incoherent. I think the chunk of America that I'm identifying offers some ballast against our country really going off the rails. I'm wondering whether you disagree with my reading of the American population.

RS: No, I don't disagree with it. I think that the red-blue structure that I adopted is partly an artifact of my subject. If I'm talking about myths as stories that are used to organize political thinking, I'm going to exaggerate the role of partisans because they are the ones who are actively using the myths. It remains to be seen whether there is a story with which that great undefined middle identifies.

GB: At the end of the book, you outline a left/Democratic vision rooted in the civil rights movement and the New Deal that you think has some chance of succeeding as a new national myth. I just wonder whether there's a built-in cap on how appealing that kind of vision is going to be to any American that doesn't already identify as a progressive.

RS: You may be right. I'm 82 years old. I've lived a long time. I think that the right-wing vision, of minority rule and of giving the country back to the “real” Americans, is a dead end. The only alternative I can imagine that makes any sense at all is one that links some notion of economic reform with social and racial justice.

GB: My concern would be that for basically my whole life, the American electorate has been a center-right electorate. So I wonder whether the trick is to use conservative language to achieve progressive ends. That way you are speaking to both red and blue America.

RS: Well, Bill Clinton tried that. Clinton tried to use conservative rhetoric to achieve moderately liberal ends, and it didn't work.

The stakes in the upcoming election are real stakes. If MAGA and the right get the kind of power that they're aiming for, they will change the way that politics works in this country. They will limit the possibility of progressive change. And I think that would be a bad thing.

The real core issue in my mind is the question of identity. If we could think of ourselves as members of a national community, sharing common interests and a common identity, we might be able to work out some kind of response to the challenges we face. But we don't think of ourselves that way anymore. We think of ourselves as an us-versus-them community. If one side benefits, the other side hurts. Stories about the way the nation is organized are dividing us.

This article originally appeared on HFG.org and has been republished with permission.