Kleinfeld is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. This is drawn from her latest paper, “ Closing Civic Space in the United States. ”

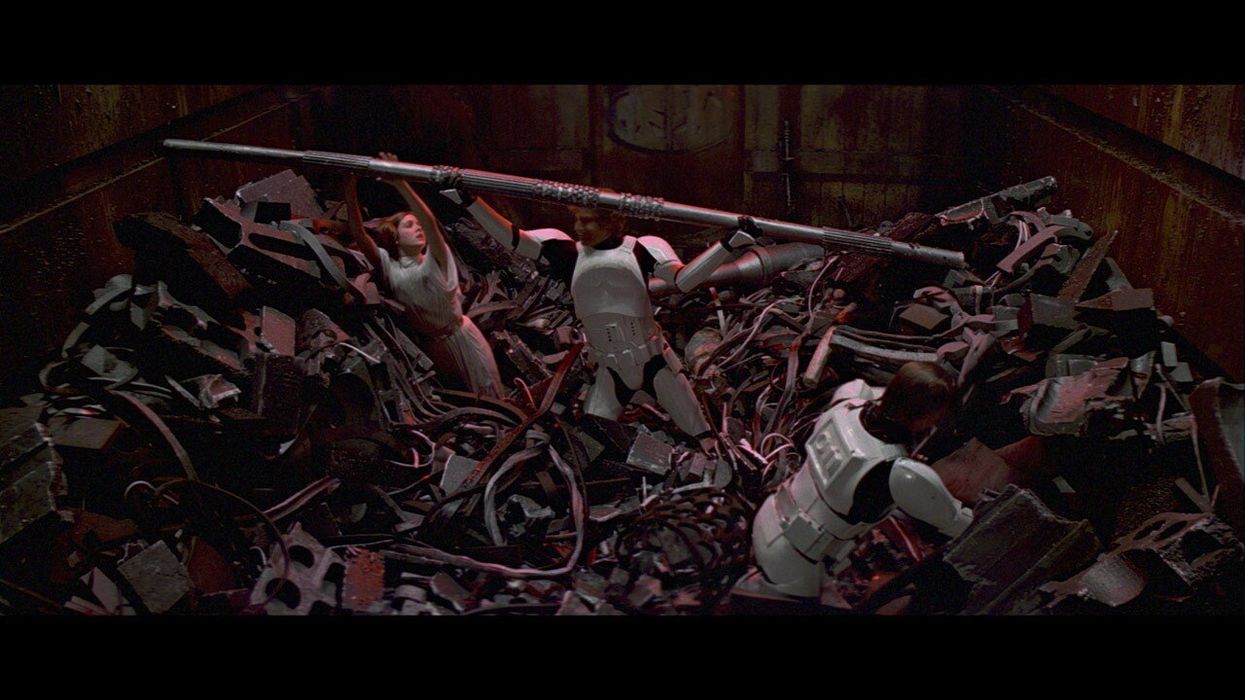

There is a scene in the first “Star Wars” where the heroes find themselves in a garbage compactor. They frantically grab for anything that can keep them from getting crushed as the walls inexorably close in. Such is the plight of civil society in countries facing what democracy experts call “ closing space ” — and it has now come to the United States.

Fifteen years ago, civil-society organizations abroad that supported ideas anathema to governing parties found themselves getting squeezed from all directions. Russia, Ethiopia, and other semi-authoritarian regimes began restricting foreign funding to their nonprofit sectors. These regimes undermined the legitimacy of organizations by painting their ideas as foreign or insinuating that their leaders were corrupt. Registration laws were crafted that made perfect compliance impossible. This indirect subversion of civil society spread globally, including within democracies: India closed 10,000 nonprofits in 2015 for minor administrative issues. Poland raided women’s and gay-rights groups and seized computers after large antigovernment protests.

Unlike under totalitarianism, not all organizations faced retribution, only groups that refused to back the ruling party’s line. Nor were activists, at first, whisked off to jail. Instead, they were weighed down with legal cases, fines, investigations, and the like until leaders burned out and funders distanced themselves from controversy.

Today, the space in which U.S. civil society operates is closing in — thanks to polarization, not a ruling party. Illiberals on the far right and far left have decided that it’s not enough to persuade: They must eliminate undesirable ideas — and organizations — using whatever power is at hand, their tactics pulled straight from those used by anti-democratic regimes abroad.

States have passed 38 new anti-protest laws. Free speech is being throttled by universities firing tenured professors for their words and by gag-order bills introduced in 36 states such as Florida. Businesses have faced state retaliation for offering customers desired products such as investment funds that employ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) screening. U.S. House of Representative committees have investigated mainstream environmental groups for failing to register under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. Fifty-year-old church ministries are suddenly facing state lawsuits.

When I looked for examples of “closing space,” I ended up with six pages. Since illiberals on the right wield more political power than those on the left, they are more likely to use governmental regulatory, legal, and oversight agencies to silence their critics. Illiberals on the left exercise more power in universities, schools, and cultural institutions; they are largely working through private regulation of speech and funding. Unprosecuted violence also plays a role in shutting down the civic sphere. Threats and violence are already terrifying many nonprofits, voter-registration efforts, and religious institutions.

Illiberals often target the other side of the political spectrum, of course: The illiberal right is harassing environmental groups and organizations pursuing LGBTQ+ rights, among others; the illiberal left has made conservatives an endangered species on college campuses. But both also obstruct the work of the liberals on their side of the partisan divide.

In fact, classical liberals on the right were the first to feel the full force of the illiberal right’s power. Powerful public leaders whose ideas may be quite conservative but who believe in the free exchange of ideas were caught unprepared. Pastors like Russell Moore were forced out. Magazines like the Weekly Standard were defunded. Intellectuals such as David French faced unrelenting, ugly, violent threats directed at themselves, their children, and their families.

Why target one’s own side? By closing space, illiberals eliminate the middle ground and reduce competition for their extreme views. That expands their power as people grudgingly accept more anti-democratic action from their own side, believing it is necessary to prevent similar actions by their opponents.

U.S. philanthropists are addressing the problem quietly and in piecemeal fashion. When grantees are targeted by cyberthreats, seven-figure lawsuits, or an attorney general’s investigation, they respond to the individual incident, with as little attention as possible.

Overseas, such a limited response failed. More organizations faced restrictions. Philanthropy itself was targeted.

In the United States, philanthropy does not have to look overseas — we can recall our own history. Space for civil society was constricted during the Jim Crow South: In Birmingham, Ala., a Junior League could operate — but an interracial league for checkers players couldn’t. In Mississippi, there was a free press, but it was illegal to publish anything supporting social equality between whites and Blacks. Groups promoting disapproved ideas might have their private insurance denied, be closed for regulatory violations, or face vigilante violence that would go unpunished.

Overseas, after a decade, philanthropists learned to band together. They set up pooled funds to defend their grantees. They supported lawyers, crisis communications, and created physical and cybersecurity programs. Programs began to whisk activists to safety if danger arose.

Luckily, we are at the early stages of closing space in the United States. And groups like the Democracy Funders Network are learning from overseas to help nonprofits and philanthropies across the political spectrum find solutions. Liberals — whether conservative or progressive — should join the effort to protect the national treasure that is America’s vibrant civil society.

This writing was originally published in The Commons.