In the early days of this second Trump presidency, I'm reminded that religious leaders often speak of hope, but now we must do so with urgency and clarity. What we're witnessing isn't just political transition—it's moral regression dressed in the garments of restoration.

When a president speaks of a "golden age" on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we must name the idolatry in such rhetoric. Golden ages, historically, have always been golden for some at the expense of many. Dr. King didn't dream of a return to any past era; he envisioned a future yet unrealized.

Recently, I've consulted with leaders across the religious spectrum. All voiced similar concerns about their respective constituencies' growing sense of unease. Lamenting their faithful who have begun concealing outward symbols of their faith, while others report feeling increasingly isolated from the broader community. These shared experiences of anxiety and disconnection point to deeper tensions within our democratic fabric.

Trump’s executive orders aren't mere policy shifts; they're moral earthquakes that shake the very foundation of our interfaith commitment to human dignity. When government policies separate families, marginalize minorities, and dismiss environmental stewardship as optional, they don't just challenge our political preferences—they assault our core religious convictions.

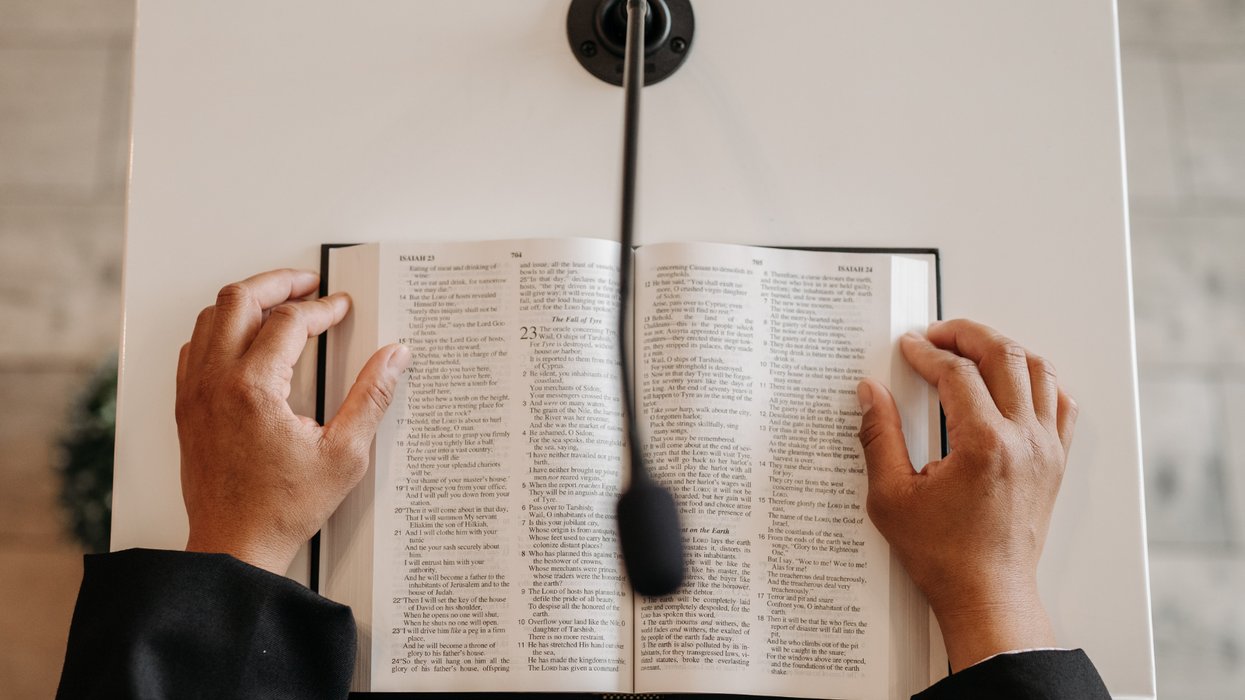

Faith leaders often misread their role in moments like these. We're not called to be chaplains to an empire, nor cheerleaders for any political party. We're called to be truth-tellers in the tradition of Amos, who understood that genuine faith always carries political implications. When Amos spoke of justice rolling down like waters, he wasn't suggesting gentle reform—he was demanding systemic transformation.

When policies target any religious community, they threaten the religious freedom of all communities. The Muslim ban of the first term wasn't just an assault on Islam; it was an assault on the First Amendment itself. Its threatened revival in this second term isn't just a migrant or political refugee issue—it's an American crisis. Our current moment demands more than dialogue; it requires collective action and "prophetic citizenship”.

What does prophetic citizenship look like in practice? First, it is transforming houses of worship from comfortable areas of convening into centers of moral action. Prayer and protest aren't opposing activities—they're different expressions of the same faithful witness.

Second, it requires reflection on what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called the “cost of grace,” which is the willingness to put something at risk for the sake of justice. When religious individuals speak of unity without addressing injustice, we offer cheap grace that heals wounds lightly, crying "peace, peace" where there is no peace.

Third, we must engage in "holy disruption"—strategic, principled opposition to policies that violate our shared moral values. This isn't about partisan politics; it's about moral consistency. The same religious convictions that lead us to feed the hungry must compel us to ask why hunger persists in the world's wealthiest nation.

To those in power who might dismiss this as mere religious rhetoric: Our resistance stems not from political calculation but from moral obligation. When you dismantle environmental protections, our sacred texts that command us to be stewards of creation require us to speak. When you demonize immigrants, our scriptures that repeatedly command us to "welcome the stranger," compel us to act.

To my fellow clerics who counsel patience: Patience in the face of injustice isn't a virtue—it's complicity. Every major religious tradition speaks of human dignity as divinely-given, not government-granted. When policies assault that dignity, our response must be immediate and unequivocal.

To those feeling overwhelmed by the scope of our challenge, take heart. Your faith is suited for long struggles. The same God who heard enslaved people's cries in Egypt hears the prayers of the marginalized today. The same Spirit that sustained the civil rights movement still moves among us. The same divine love that has carried countless generations through dark nights still lights our path.

We were created not to simply survive this moment but to transform it. Our civic responsibility isn't merely to resist what is wrong but to build what is right. In the words of Isaiah, we are to be "repairers of the breach, restorers of streets to dwell in." This isn't just poetic language—it's a practical mandate for concrete action. Our work continues, and our faith inspires us.

Rev. Dr. F. Willis Johnson is a spiritual entrepreneur, author, and scholar-practitioner whose leadership and strategies around social and racial justice issues are nationally recognized and applied.