At Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC, a new play called The American Five centers on a line that I believe defines its moral core: “If you don’t do civil rights, you won’t have civil rights.”

In the play, Martin Luther King Jr. says it to a reluctant Black lawyer who insists he “doesn’t do civil rights.” Whether or not those words appear in the historical record, their truth is unmistakable. Rights do not endure by inertia; they survive because people act.

The Play and Its Power

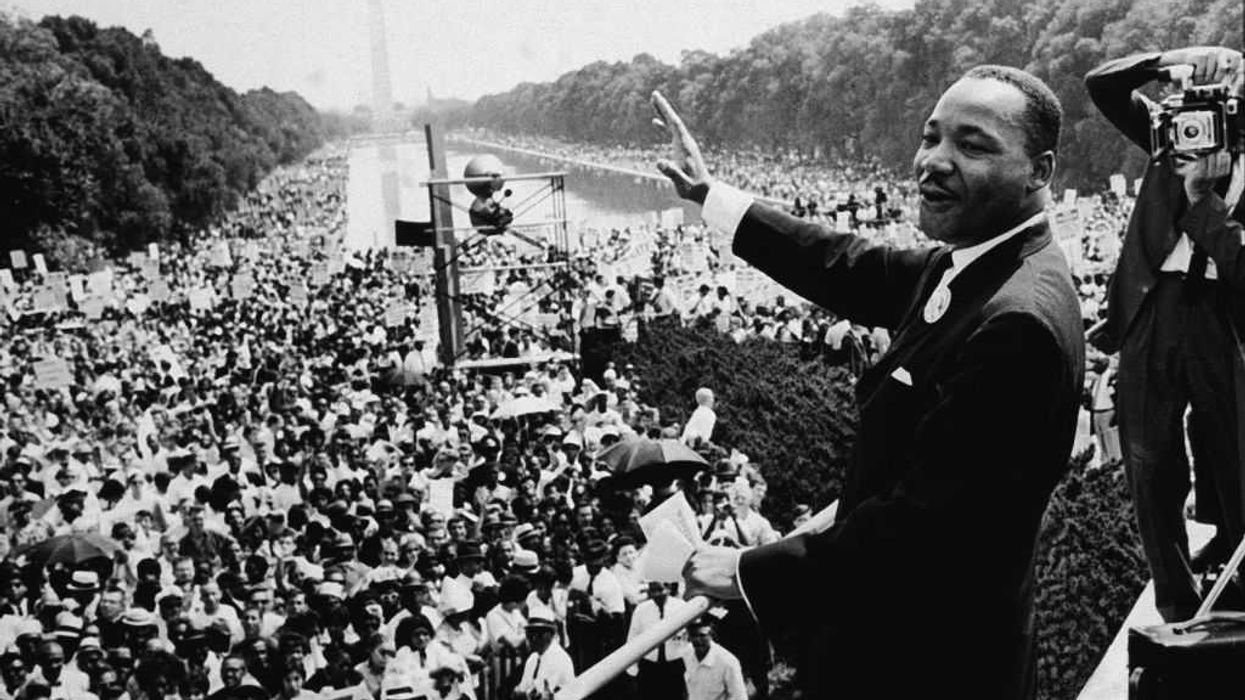

Written by Chess Jakobs and directed by Aaron Posner, The American Five follows King and four of his closest collaborators—Coretta Scott King, Bayard Rustin, Clarence B. Jones, and Stanley Levison—as they shape the language and strategy behind the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. At that march—the largest demonstration in U.S. history at the time—King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech before more than 250,000 people, calling for racial inclusion and the lifting up of all Americans through economic and social justice.

Reviews in the Washington Post and DC Theater Arts describe the production as raw and human. Actor Ro Boddie does not imitate King; he reveals him—a man balancing conviction, exhaustion, and fear under government surveillance. Jakobs shows argument, fatigue, and perseverance rather than sanctity. The play’s central line carries a simple warning that has never lost relevance: rights depend on what we do, not what we inherit. “If you don’t do civil rights, you won’t have civil rights.”

The Line as Interpretive Truth

I found no archival record of King saying those exact words, but his documented view was consistent. In his Letter from Birmingham Jail, he wrote that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” Jakobs’s line compresses that principle into a civic instruction.

Civil rights were never a natural inheritance. They were—and remain—a deliberate construction. The American Five reminds us that progress was made not by consensus but by continuous work: drafting speeches, arguing tactics, and accepting risk. Rights survive only when people do them.

Doing Rights in Our Own Time

That warning matters now because public faith in institutions has fallen to historic lows. Only about one in five Americans say they trust the federal government to do the right thing most of the time, according to the Pew Research Center. The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer reports similar declines across institutions, describing a nation more distrustful of authority and more vulnerable to its abuse.

Low trust does not hollow out democracy by itself, but it makes the work of hollowing out easier for those in power who would centralize authority and replace independence with loyalty. When citizens withdraw, the space for accountability shrinks, and the machinery of government becomes more vulnerable to capture from within.

When faith weakens, the temptation is withdrawal—to say, “I don’t do politics.” But disengagement has a cost. Bureaucracies hollow out. Extremes fill the vacuum. Silence is complicity. Expertise without moral engagement is surrender.

Authoritarian habits rarely arrive all at once. They emerge when power begins replacing competence with loyalty, when oversight offices fall silent, and when force is turned inward against those who question authority. Across the federal government, independent oversight offices have been dismantled, career officials dismissed, and enforcement powers redirected against migrants and citizens.

These are not partisan claims; they are facts reported across the political spectrum. The result has been a climate of justified fear, even in communities that once felt secure—citizens caught up in the mass detentions and street-level sweeps that have become a visible feature of domestic enforcement. These are not distant warnings; they are tests of whether we still choose to do rights inside the institutions we inhabit.

The line from the play warns against that neglect: if we do not do the work of rights, we will lose them—not suddenly, but by degrees.

Professional and Civic Citizenship

Doing civil rights can mean joining others in public action or standing up inside an institution when fairness is at risk. It means building equity into the systems we already manage—ensuring that technology, policy, and governance serve justice rather than power.

In journalism, it means independence; in education, open inquiry; in business and government, integrity. For citizens, it means showing up at the polls, in communities, and in conversation. These are the everyday acts that keep democracy alive. Every time we decide that justice is someone else’s job, we narrow the space in which justice can exist. The courage required is not always physical; it is often professional, reputational, or moral.

A Simple Instruction

“If you don’t do civil rights, you won’t have civil rights.” The words belong to a play, but their truth belongs to all of us. You do not need to be a marcher or a litigator to do rights. You can use your role, whatever it is, to resist the erosion of accountability and fairness in the systems you touch.

That is the work. If we do not do it, we will not have it. The question is not whether the cost is high. The question is whether the price of silence is higher.

Edward Saltzberg is the Executive Director of the Security and Sustainability Forum and writes The Stability Brief.