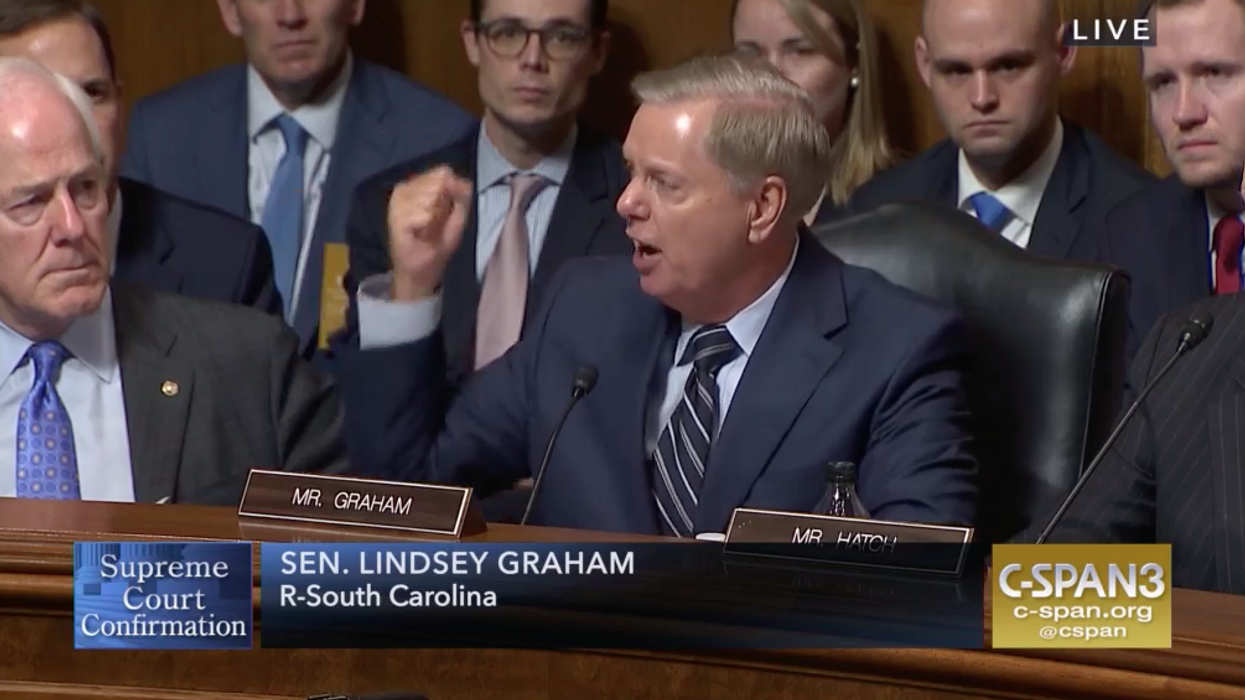

Lindsey Graham was pissed.

He shook a fist in the air, his face red and body stiff. Graham had had enough.

The whole thing was "crap," "a charade" and "despicable," the South Carolina Republican said.

By the fifth day of Senate hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, Graham was done with Democrats harping on what he considered to be a slanderous sexual assault allegation.

"This is the most unethical sham since I've been in politics," Graham said, pointing a finger across the dais of the Judiciary Committee.

The clip went viral. Fox News ate it up. And for Graham, the soundbites paid off handsomely.

During the next month, his campaign received $319,000 in large donations (more than $200) – or five times what he raised the previous month. More than 80 percent of the money came from people outside Graham's home state.

For the senator, who's seeking a fourth term next year, the takeaway is clear: Full-throated histrionics, when broadcast live for millions and replayed for days on cable news, can turn into easy money.

But for those focused on how Congress is stymied by partisanship and consumed by fundraising, the moment delivered this counterintuitive message: While putting Congress on TV has brought transparency to the legislative process, it has also created a prime venue for the sort of grandstanding that galvanizes a political base, divides a country and raises a whole lot of money.

Graham is not the first lawmaker whose outburst paid out in viral clips and campaign cash.

Just one person gave Bernie Sanders a donation above $200 in the month before a December 2010 filibuster, against an extension of tax cuts, turned him into a progressive celebrity. Within a month, his Vermont campaign coffers were $180,000 richer thanks to 308 large donations. He received 37 on the day of his Senate stemwinder alone.

And in February, arch-conservative Jim Jordan's conspiracy-theory-riddled character attack on former Trump fixer Michael Cohen at a House Oversight and Reform Committee hearing awoke a time of sleepy fundraising: Nearly $100,000 from 153 large donations poured into the Ohio Republican's account in the month after the hearing. He raised just $18,000 from 14 such donations the month before.

Of course, there were no cameras to record Preston Brooks, a states' rights congressman, bludgeoning abolitionist Charles Sumner with a cane on the Senate floor in 1856. Who knows how much cash would have funneled into Brooks' coffers had the cameras been rolling.

What the reformers have wrought

But all the networks can now catch every moment of Congress, thanks to reforms in the 1970s that authorized cameras in committee hearings and ultimately live broadcasts of floor debates in the House and Senate.

Pulling the plug on each chamber's six cameras or blacking out congressional hearings won't happen. But members of the House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress seem universally disgusted by the cameras' impact, specifically how they've been weaponized for made-for-TV partisanship now feeding a divided country and 24-hour news cycle.

The panel's hearing in March devolved into personal tales of camera-bashing. John Lawrence, a former chief of staff to Speaker Nancy Pelosi, said the decision four decades ago to open Congress to the cameras created the "unintended consequence" of fueling partisanship.

He urged limiting or even ending so-called one-minute speeches and special orders — the times when members get an open mic to speak about whatever they want and too often descend into partisan squabble-fests.

"When people out in the real world turn on the TV and they see members of Congress excoriating each other in the most hyper-partisan political way, they don't make the distinction between that and serious debate," Lawrence said. "That deteriorates the public's regard for the institution."

Few on the committee disagreed.

When Republican Dan Newhouse of Washington, who said he's long opposed cameras in Congress, turned to his colleagues and asked, "When was the last time we really had an honest, true debate in this institution?" the room fell quiet.

Democrat Emanuel Cleaver of Missouri lamented how members routinely use the floor to just "insult everybody" and that such incivility is rewarded. He pointed to the example of Republican Joe Wilson of South Carolina, who was reprimanded by the House after yelling "You lie!" at President Barack Obama during his 2009 health care speech to Congress but more than doubled his typical fundraising on the way to winning re-election the next year. Wilson is still in office.

"I don't know how we can fix that unless we understand that all of us are contributing to this dysfunctionality," Cleaver said.

Talking straight to the cameras

A body of political science research has linked extremist behavior to successful fundraising, meaning constructive dialogue isn't easy in an environment where loud mouths win dollars and re-election.

"There is a longstanding pattern in which individual donors reward extremist position-taking," University of Maryland political scientist Frances Lee said in an email. "There is no way to change the fact that ideological donors favor members who make grand gestures that push their buttons."

Like Lawrence, Lee raised a similar transparency-can-be-a-problem argument to the committee at a recent hearing.

"Limiting television cameras in committee rooms and adopting other rules that prohibit members from bringing in props that can facilitate media stunts," she said, could help Congress thwart grandstanding-for-dollars.

While no one is seriously pushing to remove the cameras, some reformers have pressed members to find more ways to meet away from the lenses.

Mark Strand, president of the Congressional Institute, a nonprofit that works to help lawmakers better serve their constituents, told the committee that members needed more "private and informal meetings and briefings" to build trust with one another "out of the public eye."

"That's key to a committee holding together and doing something in a bipartisan way," Strand said.

Aside from fundraising vehicles, cameras have become a convenient way for members to both watch their colleagues and avoid them.

"We very rarely talk to each other," noted Zoe Lofgren of California, a Democrat on the modernization committee who was a House staffer in the 1970s before the cameras were installed. Back then, members had to go to the House floor to hear a debate.

"And that meant members were on the floor listening to each other," she said. "As soon as TV came on the scene, no one came to the floor ... people no longer had to deal with each other in the way that had existed before that."

Chairman Derek Kilmer says he doesn't view cameras and a working democracy as mutually exclusive.

"Inherent to the legislative process is negotiation that doesn't always happen in the glare of the cameras," the Washington Democrat said, "but I don't think having a transparent process, having an open process, is inherently in conflict with having a functional legislative body."

The panel's top Republican, Tom Graves of Georgia, said cameras are crucial for transparency but members could benefit from time away from the spotlight to build relationships.

"It's really hard to develop public policy in one-minute sound bites – back and forth, back and forth," Graves said.

Will Trump’s moves ever awaken conservatives?