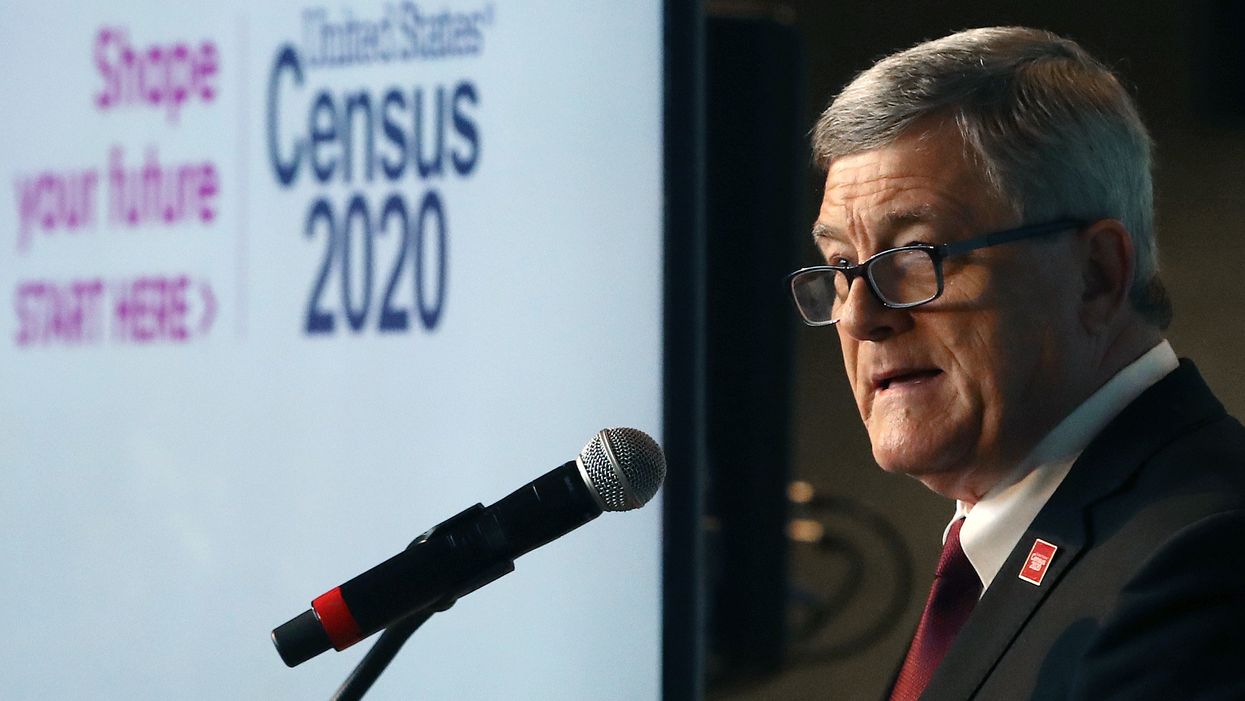

Through several hours of sometimes intense questioning, Census Director Steven Dillingham on Wednesday offered this response to House members worried about the success of the critical count that begins next month.

Don't worry. We got this.

But analysts at the Government Accountability Office, who released a new status report on the 2020 census as part of the hearing before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, are not so sanguine.

The report says that the Census is behind:

- in the hiring of people who will knock on doors to count those Americans who don't self-report.

- in the number of community partnerships it needs to establish to help find difficult to count people.

- in efforts to ensure that the technology being debuted with this census works and is secure.

A lot is at stake in the outcome of the decennial count: $600 billion in federal funds are distributed each year based on the census count and so are the number of House members each state is allotted. In addition, the census is used to draw the district boundaries for local, state and federal officeholders.

"We are confident that we are on mission, on budget and on target," Dillingham said in response to the critical GAO report.

He said the Census will surpass the goal of recruiting 2.5 million applicants for the 500,000 people who will be hired as enumerators. He acknowledged that the 240,000 community partnerships the census has established is behind the pace needed to reach the goal of 300,000 by the start of the census but it is already more than were generated for the 2010 census.

Asked by ranking Republican committee member Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio to respond to Dillingham, J. Christopher Mihm, director of the GAO's Strategic Issues team, said: "I'm from the GAO and I'm paid to worry on your behalf."

The chief concern is with how successful the officials are in convincing Americans to fill out the census form online for the first time ever.

The estimate is that 60.5 percent of people will either do that or they will fill out and mail in the paper form, if they don't respond to the initial request to go online.

But if that estimate is just a few percentage points off, it will mean millions of additional people that enumerators will need to find.

Rep. Clay Higgins, R-La., a former police officer, warned that the number of online scams in recent years will make people leery about providing personal information in an online format.

The most combative part of the hearing came when Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., castigated Dillingham for not providing a list that she and other members had requested showing the names of the census community partners by legislative district.

Dillingham said officials were checking to make sure it was OK to release the names of all of the partners.

Wasserman Schultz said she found this "baffling" since the partners are described by Census officials as "public."

Then Wasserman Schultz demanded to know who controls release of the list and asked Dillingham to promise that it would be available within the next few days.

Dillingham eventually said he didn't know exactly who was involved in the review, which Wasserman Schultz deemed "outrageous."

She accused Dillingham of deliberately withholding the list and of creating an obstacle to tracking down difficult to find communities.