Johnson is the executive director of the Election Reformers Network, a national nonpartisan organization advancing common-sense reforms to protect elections from polarization. Keyssar is a Matthew W. Stirling Jr. professor of history and social policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. His work focuses on voting rights, electoral and political institutions, and the evolution of democracies.

It’s the worst-case presidential election scenario — a 269–269 tie in the Electoral College. In our hyper-competitive political era, such a scenario, though still unlikely, is becoming increasingly plausible, and we need to grapple with its implications.

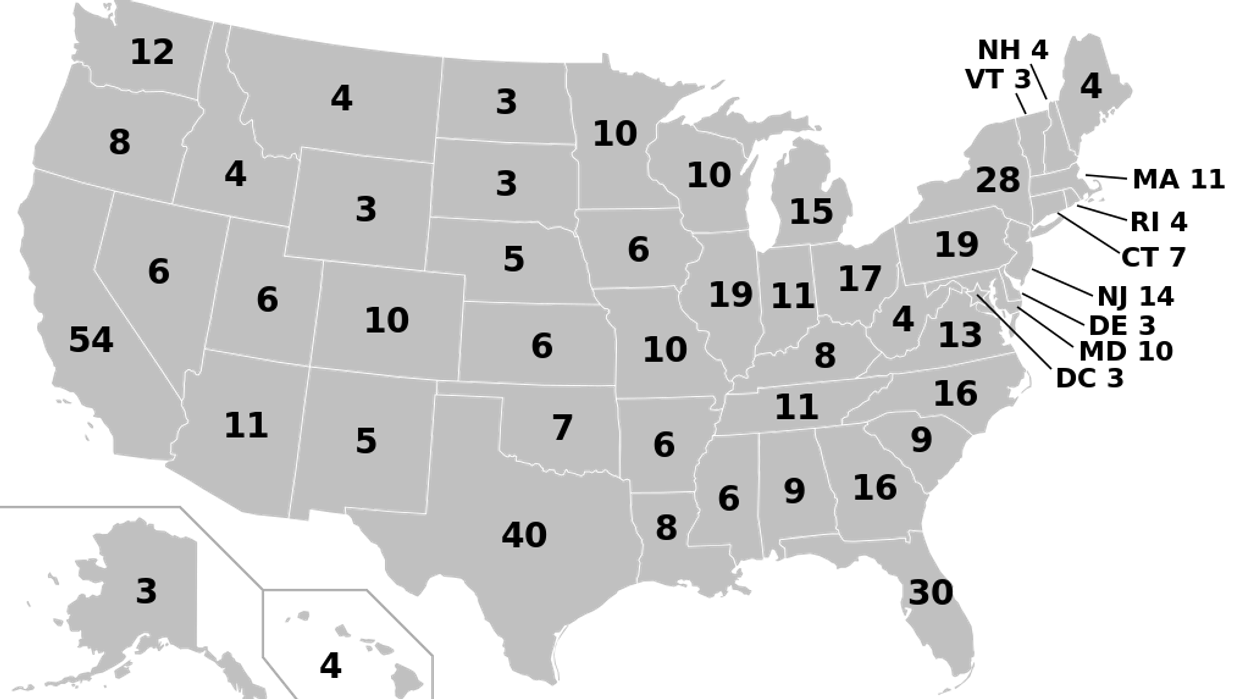

Recent swing-state polling suggests a slight advantage for Kamala Harris in the Rust Belt, while Donald Trump leads in the Sun Belt. If the final results mirror these trends, Harris wins with 270 electoral votes. But should Trump take the single elector from Nebraska’s 2nd congressional district — won by Joe Biden in 2020 and Trump in 2016 — then both candidates would be deadlocked at 269.

In case of a tie — or any scenario with no candidate winning a majority of electoral votes — the House of Representatives picks the president and the Senate chooses the vice president, and, yes, they could come from different parties. The House’s contingency election gives each state one vote, meaning Wyoming and Vermont have the same impact as California and Texas.

This year, a contingency election would almost certainly result in a victory for Trump — Republicans have held a majority of congressional delegations for many years, including when Democrats won more seats in the House. This unrepresentative tiebreaker would probably occur after a Harris popular vote victory, further underscoring the deep flaws of this system.

Of course, the chances are low the election gets “thrown to the House” — it has occurred only twice, the last time exactly 200 years ago. But even if rare, the presidential contingency mechanism impacts our politics on a regular basis.

In a democracy it should be possible — and desirable — for new parties to emerge and to challenge the status quo with policy alternatives and new leadership. But in the United States a new party faces the near certainty that its presidential candidate would throw the election to an undemocratic vote in the House or “spoil” the election by “stealing” votes from a politically similar candidate. Facing such prospects, alternative political groups often stay on the sidelines, as No Labels decided to do this year. And if parties aren’t competing for national leadership, they’ll lack the stature to compete for other major offices as well.

There are many other significant hurdles to creating strong third parties in the U.S. such as first-past-the-post elections for most public offices, anti-fusion laws and stringent ballot access requirements. Together these forces have made the United States a rarity in the democratic world. We are the only country where no new party came to power in the 20th century. Even countries like England, France and Canada that — like us — use single-member districts for the legislature have more than two parties seriously contending for power.

Our completely binary politics starves voters of a range of choices — for president, and on down the ballot. Perhaps more dangerously, binary politics fuels the vilification of opponents and the competing versions of truth that increasingly dominate our national narrative.

Removing disincentives to new party formation is a critically important goal requiring a range of reforms. This presidential season it is worth focusing on the part that the presidential tiebreaker plays. The vast majority of countries with directly elected presidents have a two-round runoff system, providing citizens the opportunity to consider new parties and enabling greater innovation and dynamism in the party system.

France is a case in point. Amid widespread political dissatisfaction, almost a dozen candidates contested the first round of the 2017 French presidential election. The surge of support for Emannuel Macron’s new Renaissance party carried him to the presidency and catalyzed a paradigm shift in French politics. The runoff rule was critical in allowing this to happen. Studies in Latin America likewise find that presidential countries using a runoff election score higher on formation of new parties and on overall democracy — as runoffs encourage moderation and give victors the “legitimacy of majoritarianism.”

We too can do this. Proposals to amend or abolish the Electoral College have circulated for two centuries, and an amendment calling for a direct popular election with runoff nearly passed in 1970. A current modification that would not require an amendment is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which would ensure a majority of electoral votes for the popular-vote winner, ending the risk of an election thrown to the House. Ranked choice voting (which is often called “instant runoff voting”) is another path to reducing the risks of the Electoral College contingency mechanism.

In 1992, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) proposed an amendment maintaining the Electoral College but establishing a second round if no candidate reached an electoral vote majority. Arguably, we could fix many of the system’s flaws by taking McConnell’s amendment and adding to it a requirement that states allocate electors proportionally rather than by winner-take-all, which would greatly expand the number of competitive states. That approach would keep the Electoral College, which many conservatives will fight hard to protect — not a perfect solution but perhaps a feasible one.

When McConnell introduced his amendment, it was Republicans who’d likely lose a thrown-to-the-House election since they controlled fewer state delegations. That’s a valuable reminder that both parties can be threatened by undemocratic Electoral College rules. Similarly, in 2004 George W. Bush came close to being a popular vote winner and Electoral College loser, and it’s certainly possible that a Republican could suffer that fate in a future election.

The challenges are huge and the record of failed attempts daunting. But we can find new ideas, alliances and motivation from understanding how the Electoral College hurts our politics on a regular basis. Addressing once and for all the archaic Electoral College is a critical step in building a robust and innovative democracy for the 21st century.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift