Klug served in the House of Representatives from 1991 to 1999. He hosts the political podcast “ Lost in the Middle: America’s Political Orphans.”

Most voters would assume that redistricting abuses are new to American politics.

Nope.

In fact, our Founding Fathers were stacking the deck when George Washington was still kicking. James Madison ran in a district designed for him so that he could be elected to Congress in order to be able to introduce the Bill of Rights.

“His friends were saying, ‘James, you have got to come back and campaign in your district because the district that has been drawn for you, as described by one person as having 1,000 eccentric angles,’” explained Sean O'Brien, executive director of the Center for the Constitution at Madison's home, Montpelier.

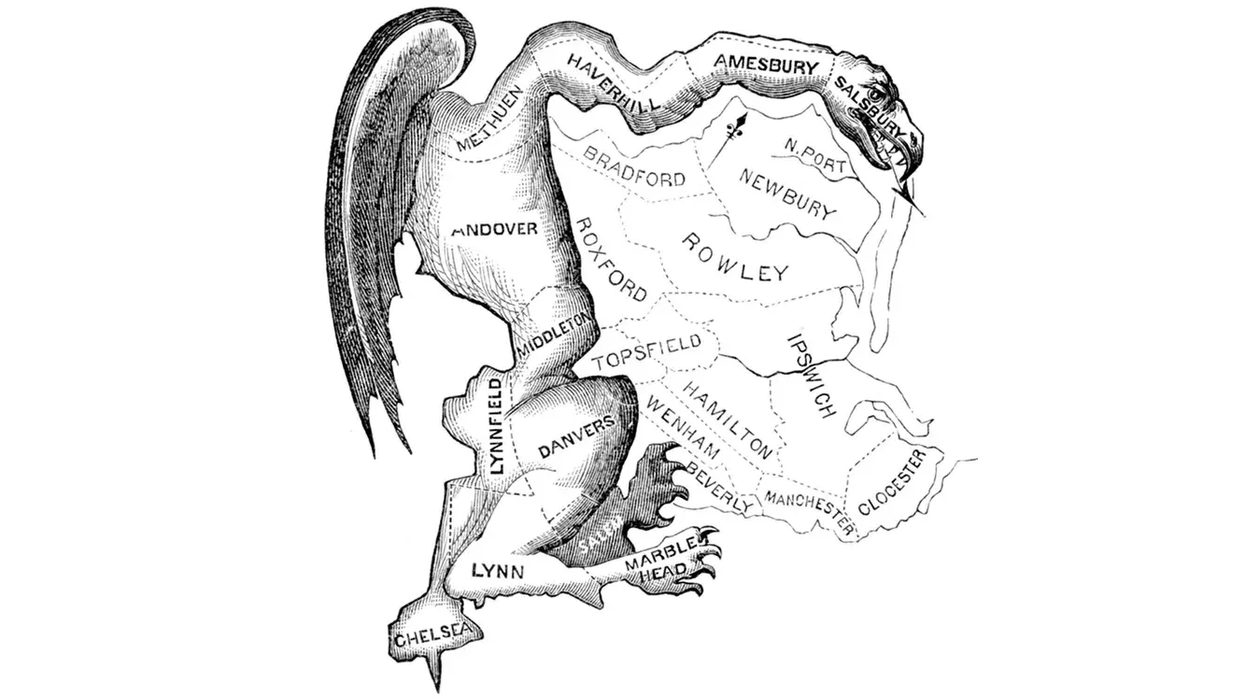

In fact, the term gerrymander came from another Founding Father, Elbridge Gerry (pronounced with a hard G), who served as governor of Massachusetts (and vice president under Madison).

“One of the offending districts kind of looked like a salamander, and so a newspaper called it Gerry's Salamander, and that became Gary Mander, then Jerry Mander,” says Harvard political scientist Nick Stephanopolus.

The push for modern redistricting reform began with the League of Women Voter in Iowa in the mid-1950s. Iowa is admired for taking the politics out of the process — today technocrats who work for the Legislature draw the maps. But in many ways Iowa is not really a model. The state is a square; the population is 97 percent white and with only four representatives it doesn’t take much careful crafting to draw fair districts.

Today 21 states have adopted variations of the commission model.

“If you look in aggregate, I'm a little bit less concerned with gerrymandering now than I was a decade ago, " says Stephanopolous. “Because in the current cycle it's balanced out more on a nationwide sort of aggregate basis. So, if you look at the House as a whole right now, I don't think it's significantly skewed in either party's favor by gerrymandering.”

As we discovered in our series on election reforms, however, even the reforms can be scammed. Listen to our podcast’s Episode 11, “Tinkering under the Hood of American politics,” to hear a doozy of a scandal in Washington state.

Tinkering around under the hood of American politics by Scott Klug

Reformers kick around ideas to improve American elections

Read on Substack

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift