Stewart is an assistant professor of Mathematical Biology at the University of Houston. Plotkin is a professor of Biology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Social media has transformed how people talk to each other. But social media platforms are not shaping up to be the utopian spaces for human connection their founders hoped.

Instead, the internet has introduced phenomena that can influence national elections and maybe even threaten democracy.

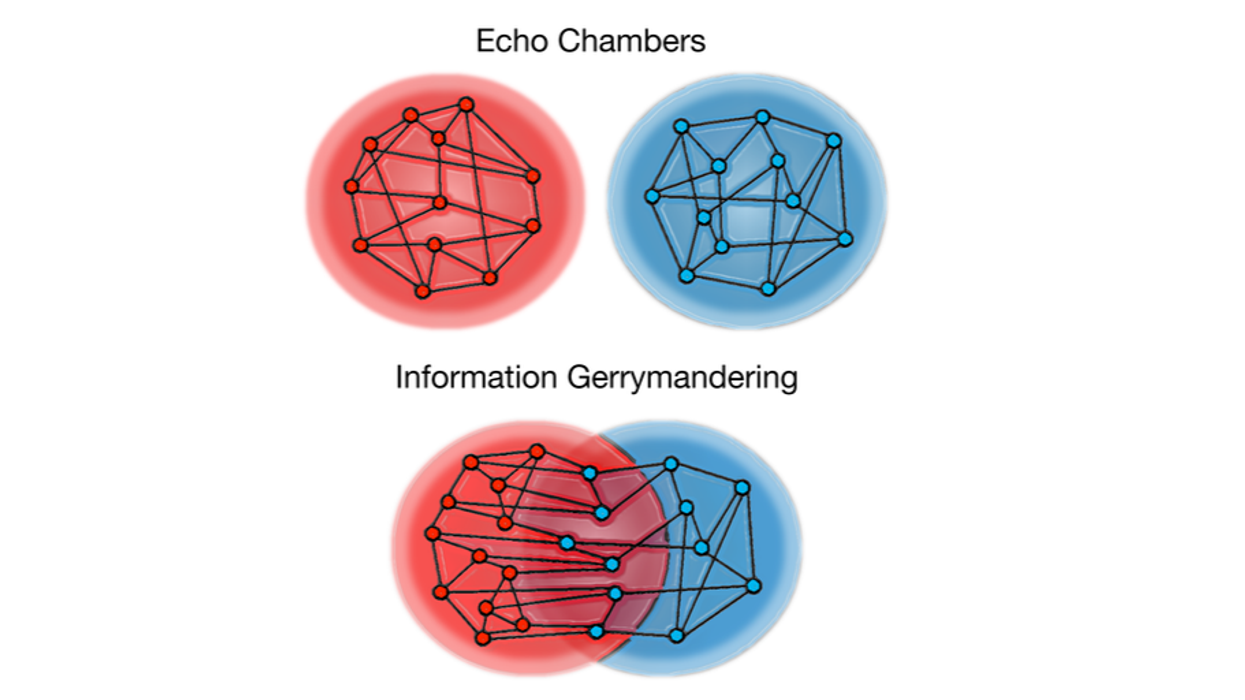

Echo chambers or "bubbles" – in which people interact mainly with others who share their political views – arise from the way communities organize themselves online.

When the organization of a social network affects political discussion on a large scale, the consequences can be enormous.

In our study released this month, we show that what happens at the connection points, where bubbles collide, can significantly sway political decisions toward one party or another. We call this phenomenon "information gerrymandering."

It's problematic when people derive all their information from inside their bubble. Even if it's factual, the information people get from their bubble may be selected to confirm their prior assumptions. In contemporary U.S. politics, this is a likely contributor to increasing political polarization in the electorate.

But that's not the whole story. Most people have a foot outside of their political bubbles. They read news from a range of sources and talk to some friends with different opinions and experiences than their own.

The balance between the influence coming from inside and outside a bubble matters a lot for shaping a person's views. This balance is different for different people: One person who leans Democrat may hear political arguments overwhelmingly from other Democrats, while another may hear equally from Democrats and Republicans.

From the perspective of the parties who are trying to win the public debate, what's important is how their influence is spread out across the social network.

What we show in our study, mathematically and empirically, is that a party's influence on a social network can be broken up, in a way analogous to electoral gerrymandering of congressional districts.

In our study, information gerrymandering was intentional: We structured our social networks to produce bias. In the real world, things are more complicated, of course. Social network structures grow out of individual behavior, and that behavior is influenced by the social media platforms themselves.

Information gerrymandering gives one party an advantage in persuading voters. The party that has an advantage, we show, is the party that does not split up its influence and leave its members open to persuasion from the other side.

This isn't just a thought experiment – it's something we have measured and tested in our research.

Our colleagues at MIT asked over 2,500 people, recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk, to play a simple voting game in groups of 24.

The players were assigned to one of two parties. The game was structured to reward party loyalty, but also to reward compromise: If your party won with 60% of the votes or more, each party member received US$2. If your party compromised to help the other party reach 60% of the votes, each member received 50 cents. If no party won, the game was deadlocked and no one was paid.

We structured the game this way to mimic the real world tensions between voters' intrinsic party preferences and the desire to compromise on important issues.

In our game, each player updated their voting intentions over time, in response to information about other people's voting intentions, which they received through their miniature social network. The players saw, in real time, how many of their connections intended to vote for their party. We placed players in different positions on the network, and we arranged their social networks to produce different types of colliding bubbles.

The experimental games and networks were superficially fair. Parties had the same number of members, and each person had the same amount of influence on other people. Still, we were able to build networks that gave one party a huge advantage, so that they won close to 60% of the vote, on average.

To understand the effect of the social network on voters' decisions, we counted up who is connected to whom, accounting for their party preferences. Using this measure, we were able to accurately predict both the direction of the bias arising from information gerrymandering and the proportion of the vote received by each party in our simple game.

We also measured information gerrymandering in real-world social networks.

We looked at published data on people's media consumption, comprising 27,852 news items shared by 938 Twitter users in the weeks leading up to the 2016 presidential election, as well as over 250,000 political tweets from 18,470 individuals in the weeks leading up to the 2010 U.S. midterm elections.

We also looked at the political blogosphere, examining how 1,490 political blogs linked to one another in the two months preceding the 2004 U.S. presidential election.

We found that these social networks have bubble structures similar to those constructed for our experiments.

The effects that we saw in our experiments are similar to what happens when politicians gerrymander congressional districts.

A party can draw congressional districts that are superficially fair – each district is contained within a single border, and contains the same number of voters – but that actually lead to systematic bias, allowing one party to win more seats than the proportion of votes they receive.

Electoral gerrymandering is subtle. You often know it when you see it on a map, but a rule to determine when districts are gerrymandered is complicated to define, which was a sticking point in the recent U.S. Supreme Court case on the issue.

In a similar way, information gerrymandering leads to social networks that are superficially fair. Each party can have the same number of voters with the same amount of influence, but the network structure nonetheless gives an advantage to one party.

Counting up who is connected to whom allowed us to develop a measure we call the "influence gap." This mathematical description of information gerrymandering predicted the voting outcomes in our experiments. We believe this measure is useful for understanding how real-world social networks are organized, and how their structure will bias decision making.

Debate about how social media platforms are organized, as well as the consequences for individual behavior and for democracy, will continue for years to come. But we propose that thinking in terms of network-level concepts like bubbles and the connections between bubbles can provide a better grasp on these problems.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift