Nevins is co-publisher of The Fulcrum and co-founder and board chairman of the Bridge Alliance Education Fund.

Every 10 years, states draw new congressional and legislative district lines. Often, mapmakers engage in gerrymandering – drawing lines in a way that artificially advantages one person, party or group over another. The anti-corruption group RepresentUs explains the ensuing problem: “Instead of voters choosing politicians, it’s the other way around – politicians are choosing their voters. They do it by gerrymandering voting districts to guarantee their own re-election. That’s corruption at the core of our political process.”

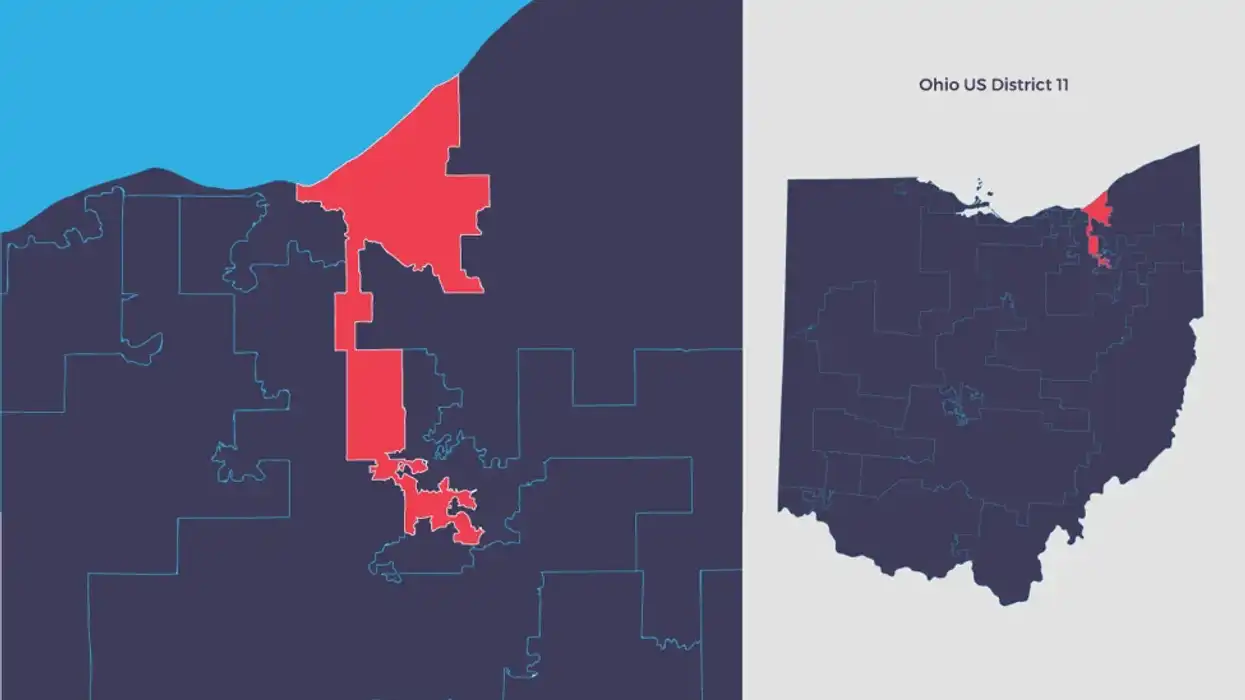

The Fulcrum ran a story in November 2019 by David Meyers that identified the 12 worst examples of gerrymandering in the House of Representatives. Meyers pointed out that you know you've seen a gerrymandered district when it looks like a duck or a snake, or even a pair of earmuffs. But he also noted that it’s not always obvious that the mapmakers played games with the contours in order to ensure a particular electoral outcome inside those boundaries.

One clear example cited was Ohio's “snake by the lake” 9th district. Jason Fierman, founder and managing director of The Redistrict Network, noted that the district – which stretches from Toledo to Cleveland – is “so thin and strangely shaped that they actually drove to Lake Erie to monitor sea levels with respect to the contiguity of the district. They are concerned that climate change could make the district non-contiguous and consequently altered in the next round of redistricting.”

This is just one of the many bizarre districts mentioned.

Most Americans oppose partisan gerrymandering, but half do not know whether the practice occurs in their states. As Meyers reported: “Two-thirds of Americans told pollsters for The Economist and YouGov that states drawing legislative districts to favor one party is a ‘major problem’ with just 23 percent saying it’s a ‘minor problem.’ But 50 percent said they do not know whether districts are drawn by the legislature or an independent commission in their own state.”

While the districts certainly may have changed in the latest round of redistricting, the depth of the problem has not. Both Democrats and Republicans continue to design maps to ensure that their party maintains power.

In February 2022, The Fulcrum reported that a poll found a majority of Americans oppose partisan gerrymandering

Fast forward to 2024.

In a survey of leading voices in the democracy reform movement, ending partisan gerrymandering and moving to independent redistricting was the third highest priority for this year (coming in after open primaries and ranked-choice voting).

In December, New York's highest court, ordered the state’s Independent Redistricting Commission to submit a revised congressional redistricting plan to the state Legislature, based on data from the 2020 Census. But on Monday the Legislature rejected the commission’s plan and assumed responsibility for drawing new lines. Democrats hold the majority and are expected to devise a plan that helps their party at the expense of Republicans.

And in Louisiana, the Legislature recently passed a new congressional map, which Republican Gov. Jeff Landry has signed into law. The latest district map was precipitated by a federal court ruling that the district lines drawn in 2022 violated the Voting Rights Act by diluting Black representation. Whether this new map will be taken to the courts again remains to be seen.

And the list goes on and on. In Wisconsin, Democrats have sued over the congressional map. North Carolina and Alabama both have new congressional maps. And in Texas, the congressional map faces several legal challenges.

Undoubtedly the redrawing of congressional lines to satisfy partisan goals will continue – as will the ensuing legal battles. In the coming weeks and months The Fulcrum will continue our coverage on this critical issue and work to identify the worst gerrymandering districts.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift