More than 80,000 people on parole or probation in New Jersey have had their voting rights restored.

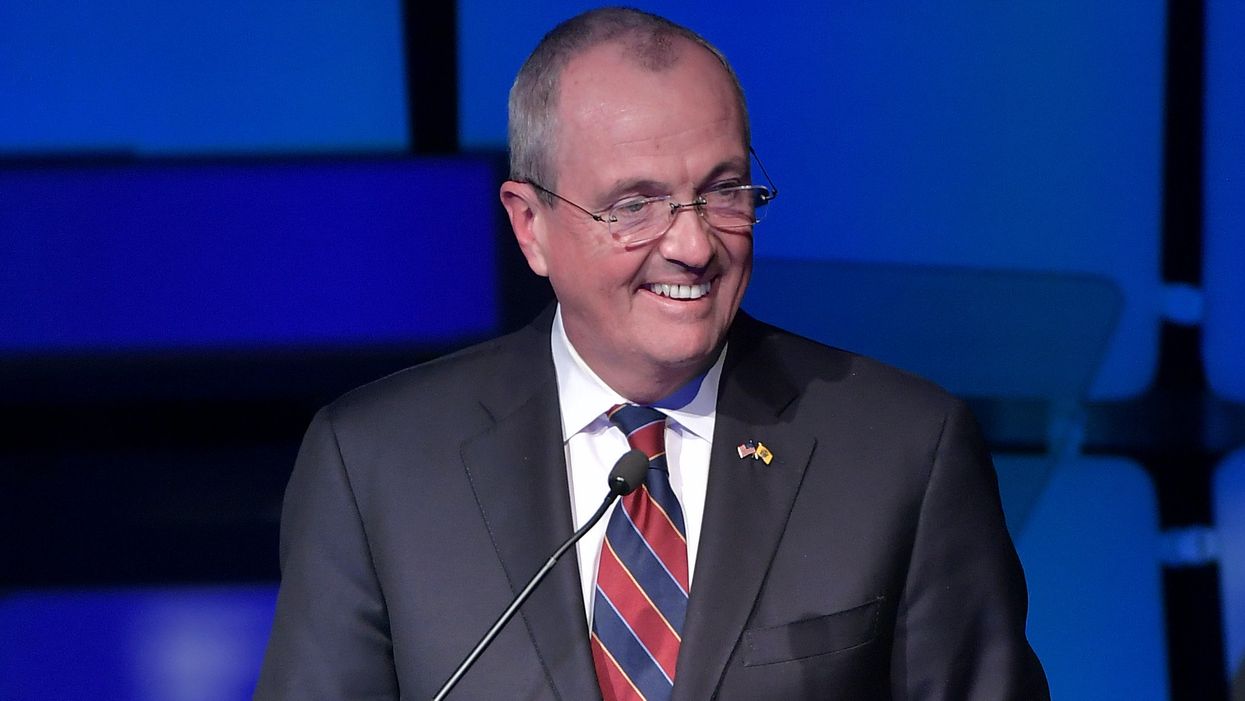

Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy signed a bill Wednesday allowing formerly incarcerated felons to register to vote starting in March, well ahead of the state's presidential primary in June. The Democratic state Senate sent him the measure Wednesday following passage by the state House last month.

It's the latest in a growing roster of states that have expanded the political rights of people out of prison, a longtime cause of those in favor of both boosting turnout and promoting the reintegration of freed felons into society.

"These are residents who are living as full participants in their communities and yet have been needlessly prevented from having a voice in the future direction of their communities," Murphy said at a signing ceremony in Trenton.

Previously, the state required those convicted of criminal offenses to complete their post-release conditions before restoring their voting rights. New Jersey has now joined 16 states and Washington, D.C., in restoring the franchise upon release.

Murphy's signature is the latest in a string of actions taken in recent years in mostly Democratic states to restore voting rights to released felons, a significant portion of whom were disenfranchised by low-level drug possession convictions.

Gov. Andy Beshear signed an executive order right after taking office in Kentucky last week restoring voting rights to more than 140,000 nonviolent felons who had completed their sentences. Gov. Andrew Cuomo did the same last year for about 35,000 New Yorkers under parole supervision. And Gov. Terry McAuliffe restored voting rights to more than 170,000 nonviolent felons in Virginia from 2016 to 2018.

Also in 2018, Florida voters approved a state constitutional amendment to enfranchise an estimated 1.4 million released felons, leaving Iowa as the only state that permanently bars those with felony convictions from voting.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift