Manjapra is a professor of history at Tufts University.

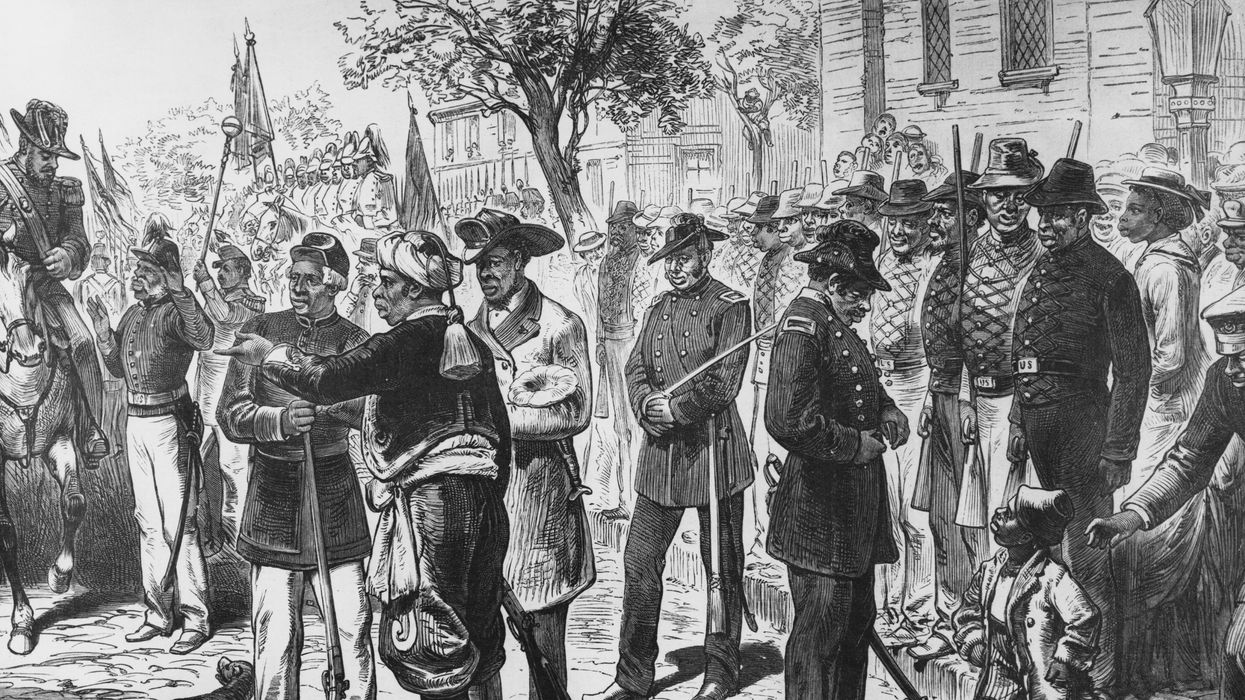

The actual day was June 19, 1865, and it was the Black dockworkers in Galveston, Texas, who first heard the word that freedom for the enslaved had come. There were speeches, sermons and shared meals, mostly held at Black churches, the safest places to have such celebrations.

The perils of unjust laws and racist social customs were still great in Texas for the 250,000 enslaved Black people there, but the celebrations known as Juneteenth were said to have gone on for seven straight days.

The spontaneous jubilation was partly over Gen. Gordon Granger’s General Order No. 3. It read in part, “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

But the emancipation that took place in Texas that day in 1865 was just the latest in a series of emancipations that had been unfolding since the 1770s, most notably the Emancipation Proclamation signed by President Abraham Lincoln two years earlier on Jan. 1, 1863.

As I explore in my book “Black Ghost of Empire,” between the 1780s and 1930s, during the era of liberal empire and the rise of modern humanitarianism, over 80 emancipations from slavery occurred, from Pennsylvania in 1780 to Sierra Leone in 1936.

There were, in fact, 20 separate emancipations in the United States alone, from 1780 to 1865, across the U.S. North and South.

In my view as a scholar of race and colonialism, Emancipation Days – Juneteenth in Texas – are not what many people think, because emancipation did not do what most of us think it did.

As historians have long documented, emancipations did not remove all the shackles that prevented Black people from obtaining full citizenship rights. Nor did emancipations prevent states from enacting their own laws that prohibited Black people from voting or living in white neighborhoods.

In fact, based on my research, emancipations were actually designed to force Blacks and the federal government to pay reparations to slave owners – not to the enslaved – thus ensuring white people maintained advantages in accruing and passing down wealth across generations..

Reparations to slave owners

The emancipations shared three common features that, when added together, merely freed the enslaved in one sense, but reenslaved them in another sense.

The first, arguably the most important, was the ideology of gradualism, which said that atrocities against Black people would be ended slowly, over a long and open-ended period.

The second feature was state legislators who held fast to the racist principle that emancipated people were units of slave owner property – not captives who had been subjected to crimes against humanity.

The third was the insistence that Black people had to take on various forms of debt in order to exit slavery. This included economic debt, exacted by the ongoing forced and underpaid work that freed people had to pay to slave owners.

In essence, freed people had to pay for their freedom, while enslavers had to be paid to allow them to be free.

Emancipation myths and realities

On March 1, 1780, for instance, Pennsylvania’s state Legislature set a global precedent for how emancipations would pay reparations to slave owners and buttress the system of white property rule.

The Pennsylvania Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery stipulated “that all persons, as well negroes, and mulattos, as others, who shall be born within this State, from and after the Passing of this Act, shall not be deemed and considered as Servants for Life or Slaves.”

At the same time, the legislation prescribed “that every negroe and mulatto child born within this State” could be held in servitude “unto the age of twenty eight Years” and “liable to like correction and punishment” as enslaved people.

After that first Emancipation Day in Pennsylvania, enslaved people still remained in bondage for the rest of their lives, unless voluntarily freed by slave owners.

Only the newborn children of enslaved women were nominally free after Emancipation Day. Even then, these children were forced to serve as bonded laborers from childhood until their 28th birthday.

All future emancipations shared the Pennsylvania DNA.

Emancipation Day came to Connecticut and Rhode Island on March 1, 1784. On July 4, 1799, it dawned in New York, and on July 4, 1804, in New Jersey. After 1838, West Indian people in the United States began commemorating the British Empire’s Emancipation Day of Aug. 1.

The District of Columbia’s day came on April 16, 1862.

Eight months later, on Jan. 1, 1863, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation that freed the enslaved only in Confederate states – not in the states loyal to the Union, such as New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky and Missouri.

Emancipation Day dawned in Maryland on Nov. 1, 1864. In the following year, emancipation was granted on April 3 in Virginia, on May 8 in Mississippi, on May 20 in Florida, on May 29 in Georgia, on June 19 in Texas and on Aug. 8 in Tennessee and Kentucky.

Slavery by another name

After the Civil War, the three Reconstruction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution each contained loopholes that aided the ongoing oppression of Black communities.

The Thirteenth Amendment of 1865 allowed for the enslavement of incarcerated people through convict leasing.

The Fourteenth Amendment of 1868 permitted incarcerated people to be denied the right to vote.

And the Fifteenth Amendment of 1870 failed to explicitly ban forms of voter suppression that targeted Black voters and would intensify during the coming Jim Crow era.

In fact, Granger’s Order No. 3, on June 19, 1865, spelled it out.

Freeing the slaves, the order read, “involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor.”

Yet, the order further states: “The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

The meaning of Juneteenth

Since the moment emancipation celebrations started on March 1, 1780, all the way up to June 19, 1865, Black crowds gathered to seek redress for slavery.

On that first Juneteenth in Texas, and increasingly so during the ones that followed, free people celebrated their resilience amid the failure of emancipation to bring full freedom.

They stood for the end of debt bondage, racial policing and discriminatory laws that unjustly harmed Black communities. They elevated their collective imagination from out of the spiritual sinkhole of white property rule.

Over the decades, the traditions of Juneteenth ripened into larger gatherings in public parks, with barbecue picnics and firecrackers and street parades with brass bands.

At the end of his 1999 posthumously published novel, “ Juneteenth,” noted Black author Ralph Ellison called for a poignant question to be asked on Emancipation Day: “How the hell do we get love into politics or compassion into history?”

The question calls for a pause as much today as ever before.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift