Lennon is the Associate Editor of The Fulcrum and a Masters student studying social entrepreneurship.

Democracy is slow. Too slow.

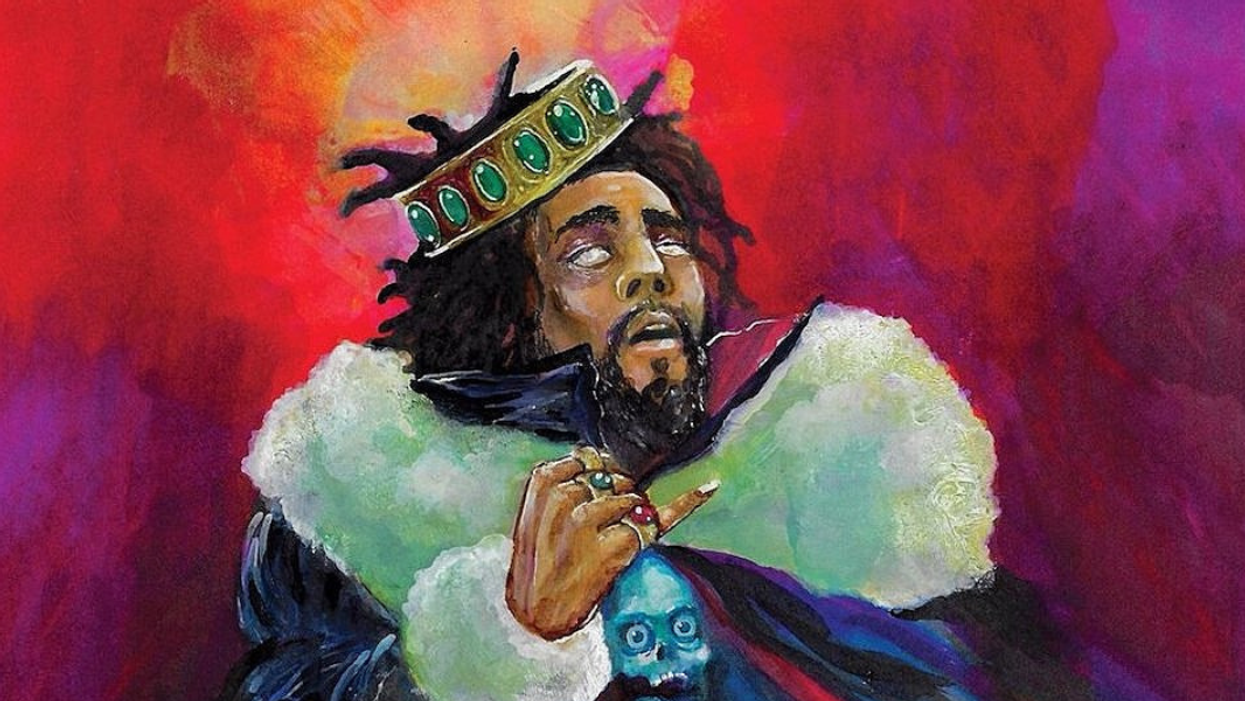

This prolonged mechanism was evident after the U.S. ripped itself from Great Britain to establish its very own democracy machine. The United States of America was subsequently established on July 4th, 1776. Yet, it wasn’t until June 19, 1865 that the idealized values set forth in the Constitution began to take flesh; slaves in Texas being informed of their Emancipation Proclamation freedoms over two years after it was set forth. As Juneteenth arrives, symbolizing both a joyous celebration and a heart-renting reminder of our stained past, still today Black Americans struggle to seize true emancipation from our country’s penchant for racism. There exists deep remnants of a stained social fabric. In J. Cole’s 2018 song, BRACKETS, he waxes poetic about the pitfalls of Black progress in the U.S. Through the lens of his words, we will navigate a modern democracy that is meant to represent all, yet often misrepresents some.

The same democratic passion that reigned on the day of the country’s independence, also reigns today. Voting rights span across democratic lines. Civil liberties are protected. Free market makes everyone an entrepreneur. And yet, we see the “American Dream” pipeline disrupted along the lines of race. It has progressed, but much too slow.

One of the most basic American economic cycles is taxation. Citizens pay taxes, those taxes are then in turn used to fund the government, which covers social programs and other basic necessities (i.e. education). Yet, in much of American history post-abolition, tax law required all Americans to pay into a machine that filtered itself through the harsh realities of the Jim Crow era; Black Americans paying into social programs that explicitly discriminated against them. Fast forward and we see this same system failing to reach the most needing Black communities, much like the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

“I pay taxes, so much taxes [it] don’t make sense. Where do my dollars go? See lately, I ain’t been convinced. I guess they say my dollars supposed to build roads and schools, but my [people] barely graduate. They ain't got the tools.”

Particularly in countries where the intent is to maintain liberties, democratic principles are meant to support citizens’ contributions to the system in kind. What is most disturbing about modern racism is the cycle of unfulfilled expectation, in which Black Americans often reap much less than they sow.

“Lord knows I need somethin’ to fill this void. Lord knows I need somethin’ to fill this void”

After the Obama presidency, Black America was supposed to see a sharp increase in democratic equity. Magically all the underlying issues of the American system were expected to dissipate. I admit, my own wishful thinking almost made me believe it. But, progress isn’t about having minorities in high office, but about having whoever is in high office, or Congress for that matter, engage in policymaking that, at minimum, doesn’t estrange Black communities.

“Maybe we’ll never see a Black man in the White House again…some older [man] told me just start voting. I said ‘democracy is too..slow’. If I’m giving you my hard earned bread I wanna know…let me pick the things I’m funding from an app on my screen. Better that than letting some wack Congressman I’ve never seen, dictate where my money goes.”

If democracy doesn’t represent Black America in full, why contribute? We do it because it is our duty, and a hope for a better tomorrow. Voting is a vital key, but one that hasn’t been allowed to maintain its effectiveness. With recently confirmed gerrymandering against the Black vote in Alabama, the onslaught against it never truly stopped; it just faded and baked its way into democracy’s fabric with the undulations of the sun. Every election cycle, politicians often look to rent the Black vote by promising to find solutions. And, we accept it because democracy is slow. Too slow.

In the process of finding actual solutions, many will look to individual characterizations in order to pinpoint the issue. Many note Black on Black violence in our country. They note single parent homes. They note disparities in educational achievement. But, as Black Americans are no more violent, nor less family oriented or educationally driven than any other strands in the American fabric, the issue lies within spheres of systemic inhibition. Guns used in gun violence don’t appear from thin air. They don’t enter any community on a magic carpet ride. The difference in the outcome of their prevalence is the civic reaction to the damage they cause on a national level; not moral goodness by the individuals affected.

“...money hungry company[ies] that makes guns that circulate the country. And then wind up in my 'hood, making bloody clothes. Stray bullet hit a young boy with a snotty nose….nobody knows what to tell his mother. He did good at the…schools unlike his brother who was lost in the streets all day”

Black mothers and fathers often fear for and mourn their children as they realize that individual accomplishment places them no closer to success bereft of a social tax that has cost many their lives. Others it has cost millions. Some others, family lineage. A tax from a source even more indirect than your Uncle Sam. But there is indeed a racism tax just as real as that from the ownership of property. And here stems the disparities in education, financial metrics, and violence statistics. The overall Black experience in America is not the same. But one thing remains consistent: inconsistency of opportunity. As the gears of American democracy turn, they often beckon Black Americans to grow through proverbial concrete.

The days of American slavery are unequivocally over. But democracy has yet to catch up to all corners of our country’s physical borders. So it’s not hard to comprehend that the pace of democracy is way too slow for Black Americans. Four-hundred years later and a seat at the democracy table still hasn’t been quite set.

Black Americans will continue to contribute. They will pay taxes. They will exercise their voting rights. They will go to work and go to school. The wheels of democracy will continue to turn and place us further and further away from the events of 1865. But how long until democracy pushes us past it, for our own sake?

“On the morning of the funeral...Wiping tears away, grabbing her keys and sunglasses; she remember[s] that she gotta file her taxes.”