Kevin Frazier i s an Assistant Professor at the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University. He previously clerked for the Montana Supreme Court.

“It takes a village to raise a child.”

It’s a common refrain. It’s commonsensical. And, it should be a common basis for the informal norms and formal policies intended to support young families. A “Leave It To Beaver”-esque upbringing should be our shared aspiration, rather than the target of skepticism. Such an upbringing is unquestionably a privileged one, but such privilege should become as common as the cold. There’s a difference between mandating a specific kind of family and celebrating the positives that come from surrounding a child with a community of support.

On a recent visit to Oklahoma City, I saw a model for such a community. At the center of that village is a toddler named Clarissa, the bundle of joy born to good friends who we visited on our summer road trip.

Within a five minute drive, Clarissa can count on at least six adults to go out of their way to ensure her well-being. A two-hour drive would bring four more adults into her village. A four-hour drive would add two more. Then there’s the entirety of the congregation at Clarissa’s church, all ready and willing to babysit, play, and mentor her.

Once I realized the breadth and depth of Clarissa’s village, it made all the sense in the world why her parents were nearly as giggly as she was. I expected to find them hassled, haggard, and hurried. Instead, the young family welcomed me and my fiancé into their home with open arms and dinner waiting on the table. Don’t get me wrong, they had plenty of stories about sleepless nights and restless days, but none of those taxing situations depleted their batteries because they knew they could count on others to step up when the crying got too loud.

Importantly, Clarissa isn’t the only one benefiting from her village. According to her parents, Clarissa has given some members of the village a new purpose and opportunity to be a part of a cause larger than themselves. In an age marked by an epidemic of loneliness, Clarissa’s role as a point of connection for adults across a wide swath of Oklahoma and Texas is worth celebrating and emulating.

A village-approach is a win-win-win-win…you get it…situation. One underappreciated win is the role village formation can play in tapping into an underused resource, the wisdom of an aging population. As our nation becomes older (and it’s graying quickly), there’s an opportunity to call on that experience to help raise our toddlers and teenagers so that they will, in turn, become valuable parts of a village down the road.

To realize the full potential of the village-approach, we will have to upend traditional limits on who can join the community, for instance, by inviting participation by members beyond our family trees. This is a big ask. Parents have every right to question the character and intentions of those who want to play a role in the life of their child. But there’s no reason we cannot develop ways to assuage those concerns and bring in members of our communal shrubbery.

Many of us have become comfortable riding in other people’s cars and staying in a stranger’s home. Given our willingness to extend our trust further in certain contexts, it seems possible that similar systems could be developed to recruit members into a child’s village. One easy way to start would be to canvas retirement homes for volunteers. My hunch is that more than a few folks would raise their hand if asked to help mentor and guide a little one.

Imagine the good that would come about by ensuring that every child had at least two grandparents, through blood or by being recruited to a child’s village, to call on for assistance and instruction. Just those two additional villagers would help parents and children alike reach their full potential.

A child isn’t the only one who needs a village. Parents rely on them. And community members yearn for them.

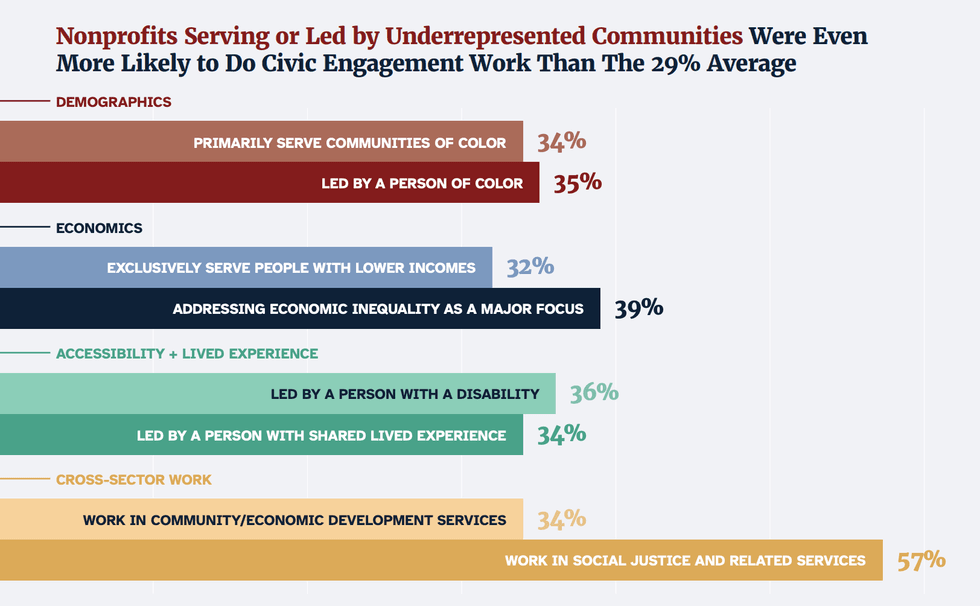

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift