Goldstone’s latest book is “Not White Enough: The Long, Shameful Road to Japanese American Internment.” Learn more at www.lawrencegoldstone.com.

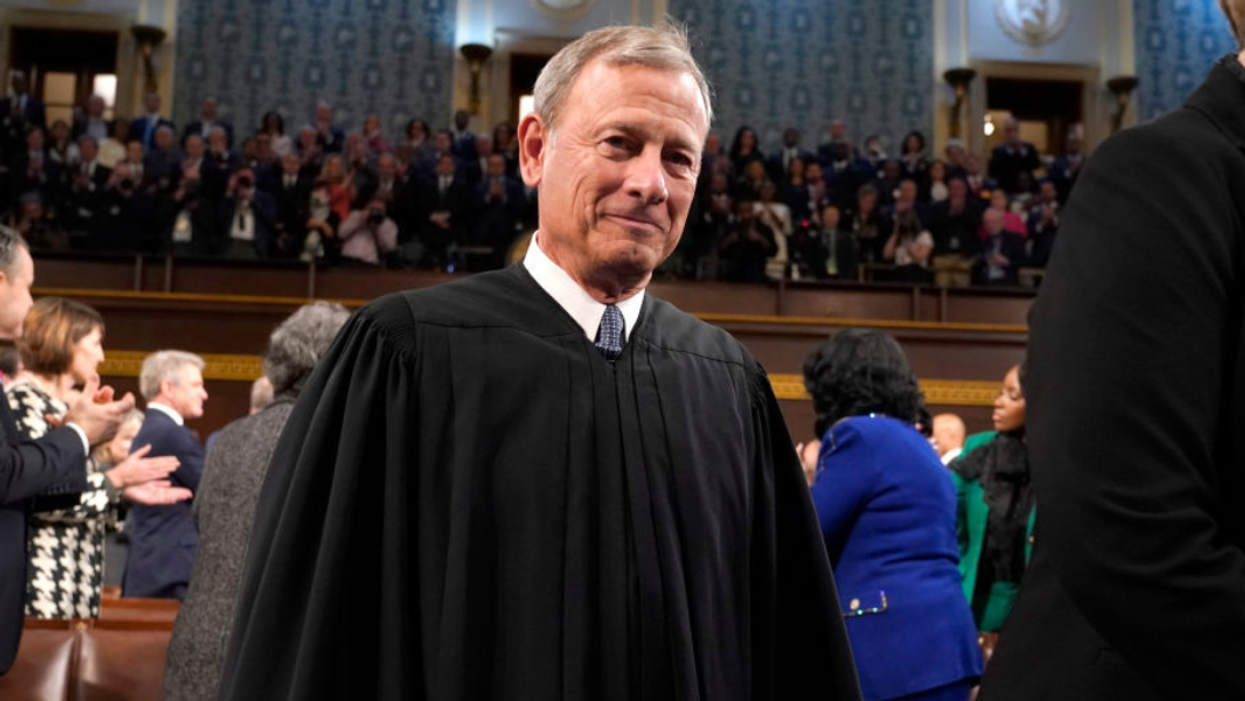

It is unlikely that the phrase “be careful what you wish for” is often applied to those very few Americans who are chosen to become the chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, but John Roberts may be well on his way to being the exception.

When the fifty-year-old Roberts assumed the center chair on the high bench in 2005, the youngest man to hold the post since his idol, the legendary John Marshall, he did so with high aspirations, nothing less than to walk in Marshall’s giant footsteps.

He spoke glowingly of Marshall’s ability to promote harmony by being “convivial,” and taking “great pride in sharing his Madeira with his colleagues.” A naturally collegial man, Roberts resolved to, “use his power to achieve as broad a consensus as possible.” But he did not intend to be a pushover. Roberts was also well aware that Marshall’s bonhomie went side by side with an iron will, which resulted in a disproportionate number of unanimous verdicts.

During his confirmation hearing, Roberts, in a baseball metaphor later employed by Samuel Alito, noted, “Judges are like umpires. Umpires don’t make the rules, they apply them. The role of an umpire and a judge is critical. They make sure everybody plays by the rules, but it is a limited role. Nobody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire.”

He prided himself on both adhering to the law and bridging ideological divides. “If I’m sitting there telling people, ‘We should decide the case on this basis,’ and if [other justices] think, ‘That’s just Roberts trying to push some agenda again,’ they’re not likely to listen very often.” He said this with the obvious belief that, with nine reasonable people sitting in the room, he could achieve results in which justices of one ideology could respect the opinions of those of another. “Judges and Justices are servants of the law, not the other way around,” he insisted.

The stakes for a man as steeped in history as John Roberts were high. Supreme Court eras are always discussed and evaluated in terms of the chief justice. It was the “Marshall Court,” or the “Taney Court,” or the “Warren Court.” And it will be the “Roberts Court.” He bears a burden that even the most prominent associate justice—Oliver Wendell Holmes or John Marshall Harlan or Antonin Scalia or Ruth Bader Ginsburg—does not. As he noted ruefully in an interview in 2007, “It’s sobering to think of the seventeen chief justices; certainly a solid majority of them have to be characterized as failures.” That the Court’s most notorious decisions, such as Dred Scott v. Sandford, are inextricably linked with their presiding chief justice provided all the incentive Roberts needed to use his vaunted social skills to avoid the same fate.

As a result, the last thing the consensus conscious Roberts would have expected was that during his tenure the Supreme Court’s approval rating would sink to its lowest level in history and the Court—his Court—would be seen by a majority of Americans as partisan, ideologically corrupt, and more of a political body than a judicial one.

Among his other woes, Roberts has recently been forced to deal with the leak of a draft opinion in a volatile abortion case, revelations that Ginni Thomas was actively involved in the conspiracy to overthrow the 2020 presidential election, and calls for an investigation of Clarence Thomas’s failure to report hundreds of thousands of dollars in gifts from a right-wing megadonor. One can only imagine how stunned and dismayed Roberts is at these unthinkable developments.

So precipitous has been the Court’s fall from grace, that one can almost feel sorry for the beleaguered chief justice.

Almost, but not quite.

Whether or not Roberts is willing to admit it, even to himself, he sowed the seeds of his present dilemma by ignoring his own dicta and adopting a political, transparently partisan agenda. To extend his umpire analogy, Roberts used a far different strike zone for each team. That he was subsequently stunned when his agenda was appropriated by a group of justices more political and more radically partisan than he is no one’s fault but his own.

Roberts’s majority opinions in two key cases highlight his willful blindness to the Court’s skew to the extreme right. In the first, Shelby County v. Holder, he ruled that key provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act were unconstitutional, thus allowing Republican-controlled states to enact legislation that would restrict the ability of Democratic-leaning voting blocs, especially African Americans, to successfully register to vote. Literally the day after he issued his ruling, a number of red states did precisely that, a trend that has continued unabated with Roberts either unaware or unconcerned that he had promoted the very sort of racial preferencing that the nation has been struggling to eliminate since the end of the Civil War.

In the second case, Trump v. Hawaii, Roberts was forced to justify a challenge to what every American over six years old knew was a politically motivated travel ban aimed at Muslims, most of whom Donald Trump had implied with his usual subtlety harbored anti-American values or were out-and-out terrorists. Sensitive to the inevitable criticism that his opinion would be compared to Korematsu v. United States, the notorious 1944 decision that legitimized the forced internment of 120,000 totally innocent Japanese Americans, Roberts wrote, incredibly, “ Korematsu has nothing to do with this case,” because, he claimed, Korematsu was openly racist, whereas his opinion was based solely on national security grounds.

Critics found that statement ludicrous, because Roberts, like Hugo Black in Korematsu, “danced around and downplayed the openly racist context from which the government’s exclusion order emerged.”

Roberts’s capitulation to conservative ideology was not restricted to his own opinions. He concurred in other decisions that stacked the political deck in favor of conservatives, such as Citizens United, District of Columbia v. Heller, and even Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Perhaps he has gotten the point, at least a bit. Although there is no way to know for certain, it is likely that Roberts lobbied vigorously during the Court’s deliberations on the mifepristone emergency petition for the Court not to add to the widespread outrage over Dobbs by becoming what would amount to a shadow FDA. If so, that would be an indication that to save his legacy, he realizes he needs to navigate back to the center, where he should have been all along.

Sorry Mr. Chief Justice. Too late.