WASHINGTON – On the 15th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s ruling on Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, and one day after President Trump’s inauguration, House Democrats made one thing certain: money determines politics, not the other way around.

“One of the terrible things about Citizens United is people feel that they're powerless, that they have no hope,” said Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Ma.).

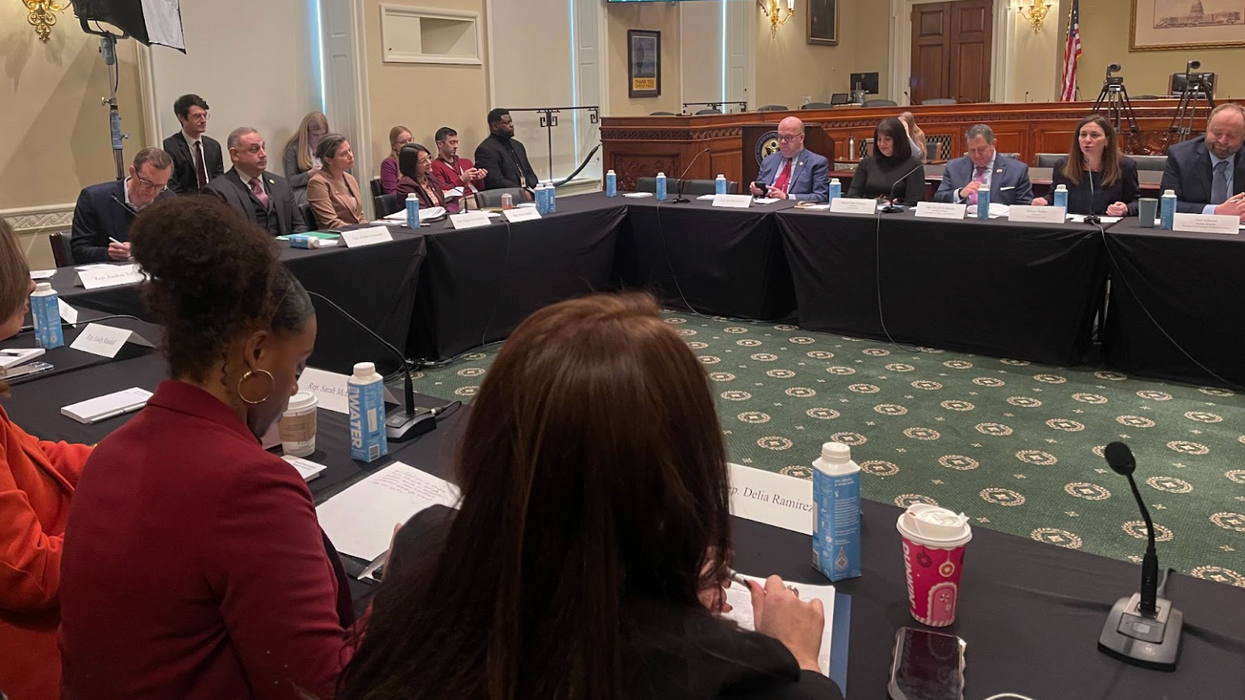

The roundtable discussion focused on the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision on prohibiting the government from restricting independent spending on political campaigns. The ruling unleashed corporate spending on elections and its impact was felt in the last election, where billionaire donors fueled Trump’s presidential win. Democrats on the Committee on House Administration convened the roundtable and only Democrats participated.

However, Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, said he supported the ruling in 2010 and still does now because the Supreme Court was correct in deciding that the First Amendment protected independent political spending by corporations and other groups.

He said Citizens United is not responsible for the “bad developments” in American politics.

“I think almost any constitutional right can potentially be destroyed by saying you're not allowed to expend resources in order to exercise the right. That's certainly true of the right of freedom of speech. If you say, ‘Well, you can say what you want, but you can't spend money to disseminate your speech or broadcast,’ that would clearly destroy the right of freedom of speech,” he said.

According to PBS News, the 2024 presidential election was the second most expensive election since the 1980s. OpenSecrets reported that the amount spent was $5.5 billion.

Tiffany Muller, president of End Citizens United, an advocacy group, told the gathering of lawmakers that the wealth of the ten richest people in the world surged by $64 billion the day after Trump was elected. She added that Elon Musk’s net worth had “increased by $200 billion just this year.”

She said the Court’s Citizens United decision was “disastrous,” and it not only opened the floodgates to unlimited and undisclosed spending, but it shut the door on getting anything done.

She said that before Citizens United, there were 14 instances of Republicans joining with Democrats to address climate change, and after it passed, the oil and gas lobby became the number one spender in elections, and “there have since been zero instances of us being able to address that since.”

Muller said yesterday’s inauguration was the culmination of the consequences of the last 15 years and the start of what she referred to as “the Billionaire’s Ball” because “just seven people donated a billion dollars to elect Donald Trump.” Now, some of them sit at the head of government agencies, “like Dr. Oz, who made a fortune as a snake oil salesman.”

In his last address to the nation, former President Joe Biden warned that rich people were having so much sway in politics that “an oligarchy is taking shape in America.”

McGovern, however, argued that the word ‘oligarchy’ should not be used because “people don’t know what that means.”

He suggested, instead, that lawmakers keep drawing the connection to show how big money influences particular policies.

“If you're on a committee that deals with healthcare, tie the fact that Trump is trying to undo efforts to lower the cost of pharmaceuticals. We have to keep making the connection,” he said.

Rep. Summer Lee (D-Pa.) contradicted McGovern, “The reality is that we need to tell the truth, and if people don't understand the language we're using, it doesn't mean that we don't tell it to them. It means that we have to get them up to speed on the language.”

Rep. Delia Ramirez (D-Ill.) joked that she could use tequila in her coffee after the witnesses’ testimony “because it all feels awful.” But she said that these issues are exactly why she believes it’s her responsibility to do everything she can to make sure that people understand the impact of money in politics.

Ramirez, a daughter of immigrants, was the first Latina ever to be elected to serve Illinois in Congress.

“It's 2025, why is that? It's too damn expensive to run for Congress,” she said.

Some legal experts said Citizens United does not determine who wins elections.

Joe Luppino-Esposito, deputy legal policy director at the Pacific Legal Foundation, said that the candidates with the most money do not always win.

“Ask [former Vice President] Kamala Harris, who spent well over a billion dollars,” Luppino-Esposito said. “She dwarfed [Trump] completely, and he still prevailed. It’s definitely not the case that whoever has the most dollars automatically wins.”

According to Forbes, Harris’ campaign raised around $20 million from big donors between October and November, compared to Trump’s $5 million.

Luppino-Esposito disagreed with the alarms Democrats raised about oligarchs.

“Every party has their own oligarchs,” he said. “Everybody has their own people that they hail as their leaders in industry. When the case came down in 2010, there was this perception that corporate money was all going to be on the Republican side of the aisle, and that is very, very far from the case. Both sides have engaged in the arms race… Trump is not as afraid to tout that these people are on his side, whereas President Biden had the same type of people on his side as well [like George Soros].”

Somin, from George Mason University, said he’s unhappy with the winners in the recent election, but he does not blame Citizens United.

“American politics since 2010 has certainly gone in much worse directions than I had expected or hoped,” he said. “I don't think Citizens United is the culprit.”

“There are going to be some people who can exercise liberty in some ways more effectively than others. If you're a famous celebrity like Taylor Swift, when you speak, many more people are going to pay attention,” he said. “With almost every constitutional right, there's some degree of inequality in the sense of how effectively you can exercise that right, but I don't think there's anything unique to money and speech in that respect.”

During the roundtable, Lee conceded that it’s not just Republicans who protect big money in politics. Democrats publicly oppose Citizens United, but their actions don't align with their words.

“In our Democratic party, we won't even get rid of money and politics… when it's just us, and we have to start to talk about the why. I am the first Black woman to represent Pennsylvania. I do not come from money,” she said. “There is no one in my phone who I can call and ask for a significant amount of money. And because there's no such person in my network, people like me are systematically blocked from representing in Congress.”

Lee added that any one who cares about mass shootings, the climate, environmental racism, or taking down Big Pharma, should care about money in politics.

“If we can't put our money where our mouth is, then we have to be very real about whether or not we are actually fighting for the best interest of the American people,” Lee said. “We can't combat Big Pharma if we are also accepting money from them. Democrats have to be more serious about serving the people, and we can't do that if we are not serious about combating our own issues with taking money in politics.”

Samanta Habashy is a student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, majoring in journalism and international studies.