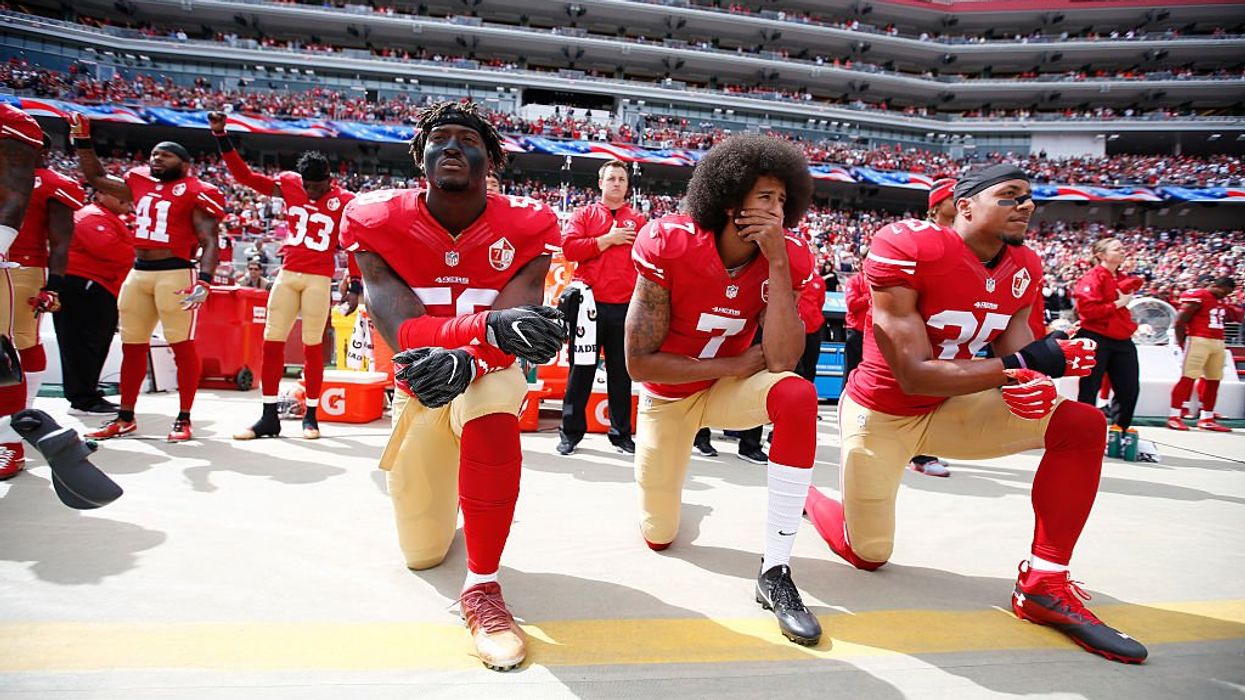

Despite the 2016-17 NFL season featuring Tom Brady and the New England Patriots’ iconic 28-3 comeback over the Atlanta Falcons in the Super Bowl, the retirement of legendary quarterback Peyton Manning, and the emergence of Joey Bosa as one of the top defensive players in the league, one monumental event stands above the rest: Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the national anthem in the heart of Donald Trump’s first term to protest racial injustice and police brutality in the United States.

Kaepernick spawned one of the most talked-about protests in the history of American sports, leading to national conversations about police brutality while earning himself severe backlash in the process.

But seven months into Trump’s second administration — which has vigorously attacked diversity, equity, and inclusion, weaponized ICE to target Black and Brown communities, and has adopted scores of other authoritarian measures — athlete activism is almost nowhere to be seen.

“[Trump is] a lot more powerful this time than he was the last time, and he seems a lot more intent on weaponizing the government this time,” said J.A. Adande, the Director of Sports Journalism at Northwestern University. “He’s placed ⅓ of the justices on the Supreme Court, and he’s got the executive, legislative, and the judicial branch all in his corner.”

With power across the government, Trump has attacked dissent around the country, even threatening to arrest former President Barack Obama on social media.

If former presidents aren’t safe, then athletes definitely won’t be.

To make matters worse, X, the most significant platform for athlete advocacy, has been taken over by Elon Musk to amplify far-right voices and squash left-wing protests.

“A part of this issue is the takeover of Twitter by Elon Musk and the diminishing of that as a form of protest on the left,” Adande said. “It’s now geared to amplify right-wing talking points. The BLM movement really gained momentum on Twitter. There’s no way that would happen today.”

But that’s not to say that athlete advocacy wouldn’t be effective against the Trump administration. Prominent athletes hold some of the biggest platforms in the world. LeBron James — who has been outspoken about many political issues, including the Black Lives Matter movement — holds 159 million followers on Instagram. His silence for the last seven months has prevented millions around the world from being exposed to modern injustices in America.

Athlete advocacy has also been effective in the past, most notably leading to the unprecedented conviction of Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer who murdered George Floyd in 2020.

“The conversation that Kaepernick wanted to initiate in 2016 was the conversation that led to the action in 2020,” Adande said. “It took a while and took an egregious reaction of watching George Floyd be killed on video to get the response that Kaepernick sought.”

2020 became one of the most effective years for protest in American history. With the country locked down due to COVID-19 and blatant instances of police violence being recorded and spread through social media, advocacy gained momentum.

“A lot of that momentum was the pent-up energy during the pandemic, and how things had been laid bare during the pandemic,” Adande said. “COVID was having a vastly disproportionate toll on Black and Brown communities … that meshed with blatantly visible instances of police brutality and the murder of Black people.”

However, that widespread action became an Achilles heel for modern protest movements. Voices were heard, and then were no longer needed.

“You protest if you feel you aren’t being heard,” Adande said. “When the league is taking your slogans and putting it on the court, and signing off on kneeling during the anthem … it took away the momentum from protesting because the protest had been heard.”

With protests already dwindling, combined with the Trump administration shifting the national conversation to immigration, transgender rights, and crime, the activism that dominated the COVID era on the left was gone. With Trump now threatening seemingly everyone who opposes him, athletes now risk their gargantuan salaries to speak out on controversial issues.

But it's their voices that can return the vigor to advocacy.

“Athletes still command the most attention-grabbing product in America,” Adande said. “Live sports and the NFL in particular are the single most popular product and command people's attention in ways that nothing else does in our culture. They have the stage, they have the microphone, they have the attention, it’s just a matter of if they want to use it.”

Jared Tucker is a sophomore at the University of Washington — Seattle studying Journalism and Public Interest Communication with a minor in History. Jared is also a cohort member with the Fulcrum Fellowship, to share his thoughts on what democracy means to him and his perspective on its current health.