Savenor is the executive director of Civic Spirit, a nonpartisan organization that provides training and resources to faith-based schools across the United States.

In an age of intense political divisions and polarization, it can be easy to yearn for simpler times and even the “good old days.” In actuality, our ancestors faced their own challenges and wrestled with differences that may have felt like obstacles to the future.

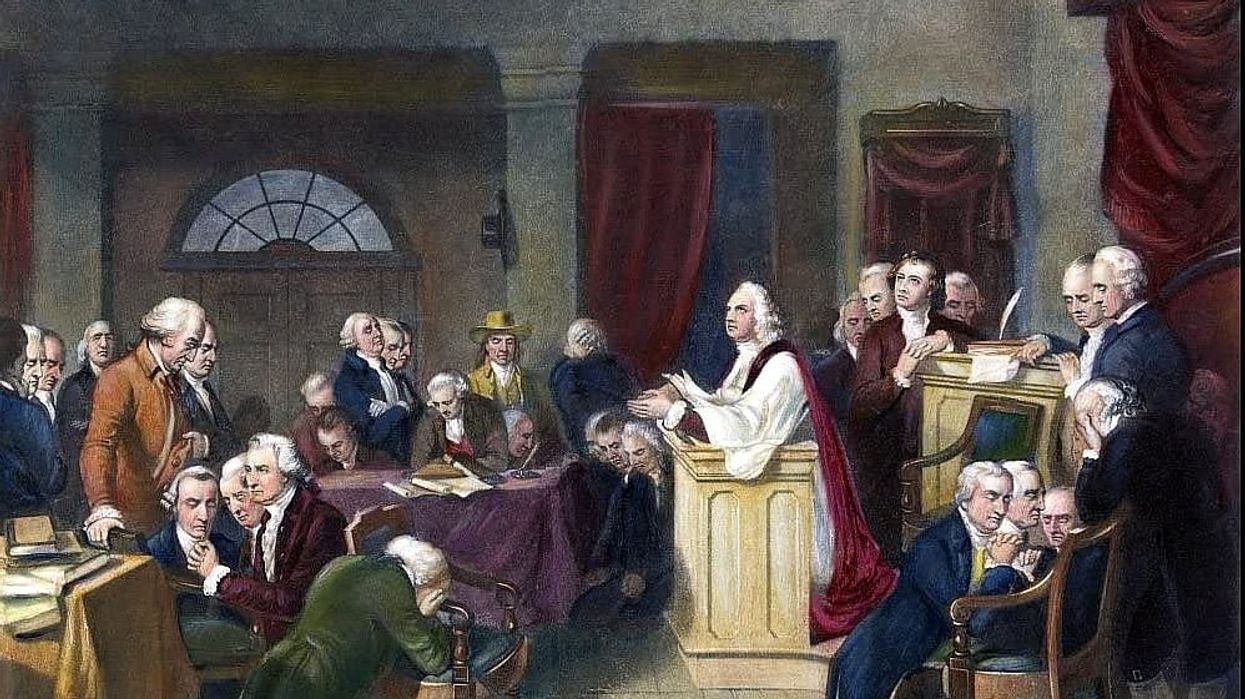

One such example unfolded on the very first day of the Continental Congress in September 1774. When one of the delegates suggested that the session begin with a prayer, there was a great deal of pushback, for the delegates represented a variety of religious beliefs ranging from Anabaptists to Quakers. Seeking to bridge the divide, Samuel Adams of Boston convinced his peers to move forward by asserting “that he was no bigot, and could hear a Prayer from any gentleman of Piety and virtue who was at the same time a friend to his Country.”

The assembly opened the Sept. 7 session with the Rev. Jacob Duche offering several prayers. Remembered most vividly was the Philadelphia clergyman’s reading of the first three verses Psalm 35, which states: “Of David. O Lord, strive with my adversaries, give battle to my foes. Take up shield and armor, and come to my defense. Ready the spear and javelin against my pursuers; say to my spirit, ‘I am your deliverance.’”

John Adams described the response to this prayer in a letter to his wife, Abigail: “I must confess I never heard a better prayer ... with such fervor, such ardor, such earnestness and pathos, and in language so elegant and sublime for American [and] for the Congress. ... It has had an excellent effect upon everybody here.” While the words of this man who would become our second president convey the spirit of this moment, generations later we wonder what was behind the impact.

Several theories attempt to explain why Psalm 35 resonated so deeply with the members of the Continental Congress that day. One view suggests that the founders were inspired by the identification of America with the biblical David fighting victoriously against England, representing the giant Goliath. Philosopher and theologian Michael Novak believes, “It was the providential and covenantal mission that has enabled Americans, past and present, to overcome their differences and to unite their individual agendas into a common destiny.”

I suggest that inspiration emanated from finding a way forward. What began as a cacophonous debate transformed into a harmonious moment generating civic spirit to embrace common purpose.

Two and a half centuries later, that moment of American history inspires the work of democratic and civic education organizations, including Civic Spirit, with which I am affiliated. Our mission is to educate, inspire and empower schools across faith traditions to enhance civic belonging, knowledge, and responsibility in their student and faculty communities. We believe this investment of hope, love and energy will yield the next generation of engaged citizens and civic leaders who will overcome their differences and chart a course for our country with common cause.

At the conclusion of John Adams’ letter to his beloved wife, he beseeched Abigail to read Psalm 35 and share it with her friends. In the same vein, I encourage all of us to share the story of the Continental Congress and the courageous evolution of American democracy to show what is possible when we find common cause.

American society needs this sentiment in 2024 more than ever. With a commitment to education, conversation and collaboration a brighter future is within our reach.